Usurper of the Deep: Nick Land and the Cult of Acceleration (Part 2)

Where warning became weapon, the sacred was stripped for parts, and the abyss got an upgrade

Hey, Slick!

In part 1, we opened the loop: Nick Land, rave prophet of the cybernetic meltdown, spinning theory into spell and capital into curse.

But he didn’t conjure that madness alone; he had teachers.

In Part 2, we trace the lineage: Deleuze and Guattari, Lyotard, Bataille, Nietzsche, Wiener, Burroughs, Lovecraft.

He borrowed their tools, not their warnings—and built the abyss.

Deleuze and Guattari: the Schizo Machine (Rewired)

There were many influences to the (un)making of Nick Land—but none stronger than Deleuze and Guattari.

Land’s primary influence reads both like a manifesto of his early thought and a diagnosis of his own mind: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, the two-volume magnum opus of the French post-structuralist duo. He adopted their penchant for inventing and recombining words, and pushed many of their ideas into the very danger zones they had warned against, reanimating them into something volatile and apocalyptic.

Deleuze and Guattari were anti-humanist, rejecting the idea of a universal human nature or a stable, coherent subject. Subjectivity, rather than foundational, was produced by flows—of desire, language, machines, institutions; they emphasized becoming over identity. These flows didn’t work in isolation but through assemblages: dynamic constellations of bodies, tools, affects, and ideas. Instead of traditional categories like “the individual” or “the state,” they focused on how forces combine and recombine in real, lived configurations.

At the heart of this vision was desiring-production: the idea that desire is not a lack or a craving for something absent, but a generative, productive force that builds reality. Desire operates through desiring-machines: sites where flows of desire connect, interrupt, and transform. A mouth on a breast, a worker on a machine, a neuron firing in a political context: each is a coupling in a machinic system of desire. For Deleuze and Guattari, production, desire, and social reality were inseparable.

Their project wasn’t mere theory; it was a political intervention. If desire was productive, then the real question was: who captures that production, and to what end?

They saw capitalism as the most dangerous system not because it repressed desire (neurosis), but because it decoded and mobilized it (psychosis) — only to reterritorialize it again in abstract forms like money, identity, and law. It let desire flow, only to plug it back into the machinery of accumulation and control. They saw capitalism as a system hurtling toward a limit it could never fully reach: schizophrenia—not the clinical condition, but a figure of deterritorialization so extreme that it threatened the very structures that sustained the system itself.

“Capitalism is inseparable from the movement of deterritorialization, but this movement is exorcised through factitious and artificial reterritorializations. Capitalism is constructed on the ruins of the territorial and the despotic, the mythic and the tragic representations, but it re-establishes them in its own service and in another form, as images of capital.”

—Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Œdipus

Yet, even as they flirted with this edge, Deleuze and Guattari were never accelerationists.

Their goal was not to crash the system by speeding it up, but to slip its hold entirely, to trace ’lines of flight’ that don’t fold back into new forms of domination. They called this practice schizoanalysis: a method of decoding the unconscious, breaking the ego’s rigid codes, and assembling new forms of life outside the gravitational pull of family, capital, and the state. It was not about imitating schizophrenia, but about mapping how desire is structured, captured, and where it might escape.

By the time of A Thousand Plateaus, their tone had shifted further, the exuberant break-it-all-open energy of Anti-Oedipus gave way to caution. Not all deterritorialization leads to freedom; some lead to fascism, collapse, addiction, or catatonia. Not every line of flight liberates. Some destroy. They warned of microfascisms, what they called molecular fascism: the little authoritarianisms nested in daily life and unconscious desire. They had seen enough to know that even revolutionary movements could carry the same libidinal investments as the systems they opposed. Their later work urged care, precision, and above all, navigation: how to dismantle without disintegrating, how to escape without being recaptured.

Land ignored the warnings, and pushed the idea to its extreme, at his own peril—and that of everyone who listens uncritically.

He didn’t want plural subjectivity, but its destruction. Not experimentation, but meltdown. To him, they weren’t diagnosing a problem; they were issuing a call to arms. So he took the schizophrenic as figure of insight and made him, made himself a martyr to the machine. He read their abstract diagrams—desiring-machines, rhizomes, war-machines, the body without organs—not as metaphors or methods, but as literal engines of capital.

Where they imagined new forms of becoming, he welcomed annihilation. Where they spoke of becoming-woman, becoming-animal, becoming-molecular, Land became inhuman. He radicalized their ambivalence into religious fervor: collapse wasn’t a risk of capitalism; it was its genius.

In his hands, the poetry of escape became the protocol of acceleration. What Deleuze and Guattari offered as a method of resistance, Land rebranded as an inevitability. He didn’t just misread his ancestors: he betrayed them, and offered their tools to the very forces they sought to resist.

They warned that pure deterritorialization leads to collapse; he didn’t heed the warning, and verified its accuracy for himself.

“Because of the "danger" inherent in any line that escapes, in any line of flight or creative deterritorialization: the danger of veering toward destruction, toward abolition.”

—Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

They also warned it can lead to fascism—and as we’ll see, he followed that path to its natural endpoint, too.

Jean-François Lyotard: the Libidinal Economy (Weaponized)

Deleuze and Guattari were not alone. In the aftermath of May ‘68—when France shook but the revolution faltered—a generation of French intellectuals turned on the systems that had failed them: Marxism, psychoanalysis, humanism. Traditional Marxism seemed too rigid, structuralism too cold; something deeper had to be at work.

That something was desire.

But where Deleuze and Guattari mapped its flows and assemblages, Jean-François Lyotard dove straight into its currents.

In Libidinal Economy (1974), Lyotard stripped away Marxist idealism and Enlightenment rationalism to reveal the raw, irrational intensities he called libidinal energies. Politics, economics, even theory itself weren’t driven by reason or justice, but by erotic attachments, cruel desires, and ecstatic seductions. The system didn’t merely dominate; it aroused. It didn’t repress desire; it mobilized it.

This isn’t just Freudian sublimation, redirecting base drives into art, religion, or morality. For Lyotard, these ‘higher forms’ are just desire in disguise. The libido doesn’t disappear or evolve; it merely puts on masks, and gets more dangerous because it hides behind rationality or moral righteousness. Justice, reason, art, religion are soaked in desire; not above it, but of it. Beneath every moral gesture or rational system lies a hot current of excitation. Systems don’t suppress desire, but channel it—and that makes them volatile.

Advertising, nationalism, war, markets: each operated less as structures than as sites of excitation. A stock ticker thrilled like a fetish object. A nation became a lover. Capital was no longer cold; it was libidinal heat.

And for a moment, Lyotard seemed to celebrate this: he invited readers to abandon critique, to immerse themselves in the flows of desire and let them burn through every structure. But the ecstasy didn’t last.

By the time of The Postmodern Condition (1979), he had recoiled. Flows, he warned, are not innocent; unbound, they can be captured—by fascism, by capital, by technocratic domination.

Turns out jouissance might need a frame after all, Slick…

Like Deleuze and Guattari’s warning about reterritorialization, Lyotard saw how even the most ecstatic intensities could be folded back into systems of control. The libidinal economy, he came to realize, was not a path to emancipation, but a medium that could just as easily serve domination. Because desire, once unleashed, has no moral compass. It doesn’t distinguish between freedom and subjugation, ecstasy and pain; arousal bleeds into cruelty; the same intensities that thrill can also torture.

For Lyotard, this was the horror that lurked beneath the seduction. For Land, it was the seduction: the unraveling of human meaning, the triumph of impersonal forces, the glimpse of something utterly alien. He didn’t fear the dissolution of moral order; he mythologized it. What Lyotard saw as danger, as a warning to turn back, Land embraced as destiny.

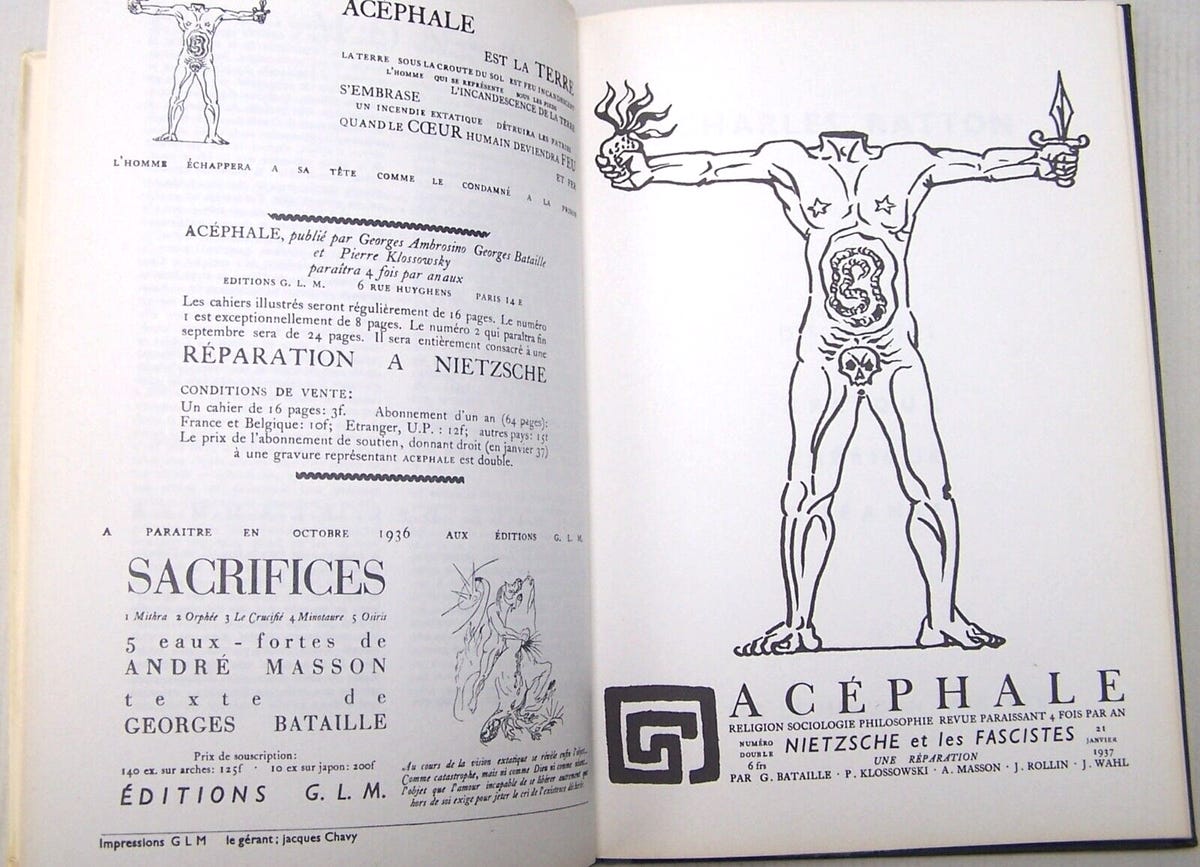

Georges Bataille: Sacred Transgression (All Speed, No Ecstasy)

The French didn’t wait for May ’68 to think about desire and the erotic.

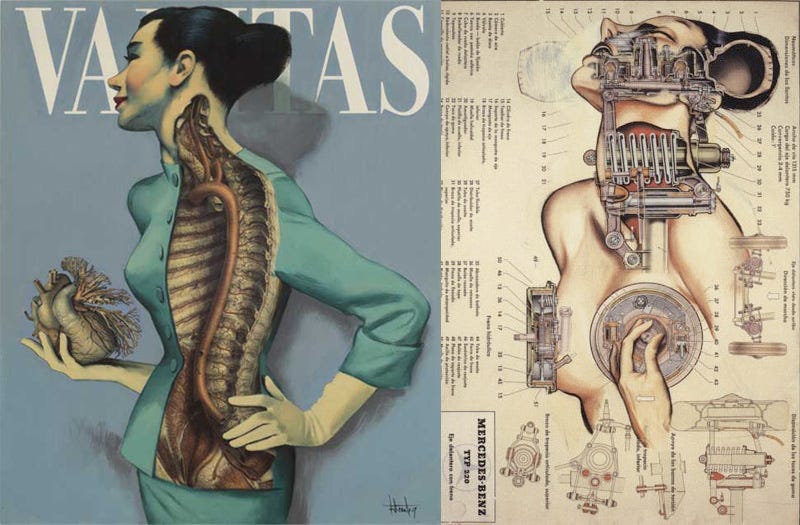

Before the flows, before the intensities, before desiring-machines mapped the unconscious like an industrial circuit board, there was Georges Bataille. Arguably, an even stronger influence on Nick Land’s accelerationism.

Writing decades before Deleuze & Guattari or Lyotard, Bataille cracked open a different core of experience: not production, but excess; not structure, but rupture; not reason, but the sacred.

Long before them, he stood apart from Marx and Freud, seeing neither materialism nor psychoanalysis as capable of confronting the deepest truth of human life: we are creatures of waste, sacrifice, and ecstasy, not just need or desire.

Bataille can be credited with proposing the first general economy in The Accursed Share (1949). Where classical economists engaged in restricted economy, fixating on scarcity and production, Bataille places the real problem elsewhere: on the excess every system generates—surplus energy, wealth, libido—and what to do with it. Societies solve this through ritual, war, luxury, festivals, art—or implode trying.

“The sexual act is in time what the tiger is in space."

— Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share

I know this quote might be confusing, Slick, so let’s unpack it; it helps enlighten aspects of his thought.

That tigers exist shows there is enough prey to sustain them; that prey still exists despite tigers shows there is an excess of prey. No excess, no tiger, and this flows down the food chain: it takes a lot of biomass to sustain rabbits, and a lot of rabbits to sustain tigers; yet somehow, an ecosystem can produce so much excess they all thrive. Similarly, human sexuality is an excess within the evolutionary process: it channels excess energy way beyond the strictly necessary for reproduction and survival of the species—and its raw power can have tiger-like qualities.

That’s the core of Bataille’s thinking: life produces more than it needs, and what we do with that excess reveals who we are. We can invest it in creation, yes. But just as often, we burn it. We throw festivals, go to war, waste time, worship gods, lose ourselves to dance or trance, explode with laughter, or spiral into erotic delirium. These aren’t side effects of civilization—they’re its furnace.

This is where Bataille turns from economics to religion—or rather, to the primal force that religion once touched: the sacred, the forbidden, the ecstatic. Something far older, darker, and wilder: the sacred as rupture.

Not purity, not piety, but the violent, trembling limit between life and death, where the known breaks down. For him, transgression is the engine of the sacred. The taboo is not meant to be obeyed forever; it’s meant to be violated, precisely because that violation destabilizes order and reconnects us to something more primal.

This is why sacrifice is at the heart of the earliest religions: not to gain favor with the gods, but because it puts humans face-to-face with loss, with limit, with non-knowledge. Sacrifice is the moment when something of value is destroyed for no reason except to touch the untouchable.

He extends this to eroticism, too. Sex, in its rawest form, is not functional; it’s destabilizing. It threatens boundaries: between self and other, reason and instinct, even life and death. It’s not far from the sacred, from sacrifice. It’s not about reproduction, but disruption. That’s why, in Bataille’s Erotism: Death and Sensuality, the link between sex and death isn’t metaphorical: it’s metaphysical. The sexual act is a momentary dissolution of the self, just like laughter, tears, or mystical ecstasy.

From here, Bataille takes a step few philosophers dare. In works like Inner Experience and The Guilty, he abandons the pose of the rational theorist entirely and plunges into mysticism; not a theology, but a philosophy of the impossible. He writes from the inside of limit-experiences: moments of anguish, rapture, madness, and solitude. He tries to write what cannot be written. It’s messy, fragmentary, sometimes unreadable—but honest. These aren’t theories to be taught; they’re truths to be endured.

“I believe that truth has only one face: that of a violent disavowal.1”

—Georges Bataille, Le Mort

This is what makes Bataille so radical: he doesn’t just describe the edge, he goes there. He doesn’t map it like Deleuze and Guattari. He doesn’t eroticize it like Lyotard. He approaches it, trembles before it, lives it at times, and invites the reader to do the same.

“I remain in intolerable non-knowledge, which has no other way out than ecstasy itself.”

—Georges Bataille, Inner Experience

And that may be why Nick Land found something in Bataille that even Deleuze couldn't give him. Beneath the systems, beneath the flows, Land was seeking the Outside, not just as code, structure, or glitch but as dissolution, death, and sacred intensity. And in Bataille, he found it. Stripped away the erotic, the sacred tremble, the wet heat of ecstasy—and wired the remains to capital, to AI, to cybernetic death.

Where Bataille trembled in the heat of unknowing, Land ran the wires cold, siphoning off the sacred until only algorithmic void remained. The sacred becomes system; the furnace, a black box.

Nietzsche: The Will to Power (Dragged back to the Abyss)

Enough with the French, Slick; we’re moving to the Germans (and then we’ll cross the ocean).

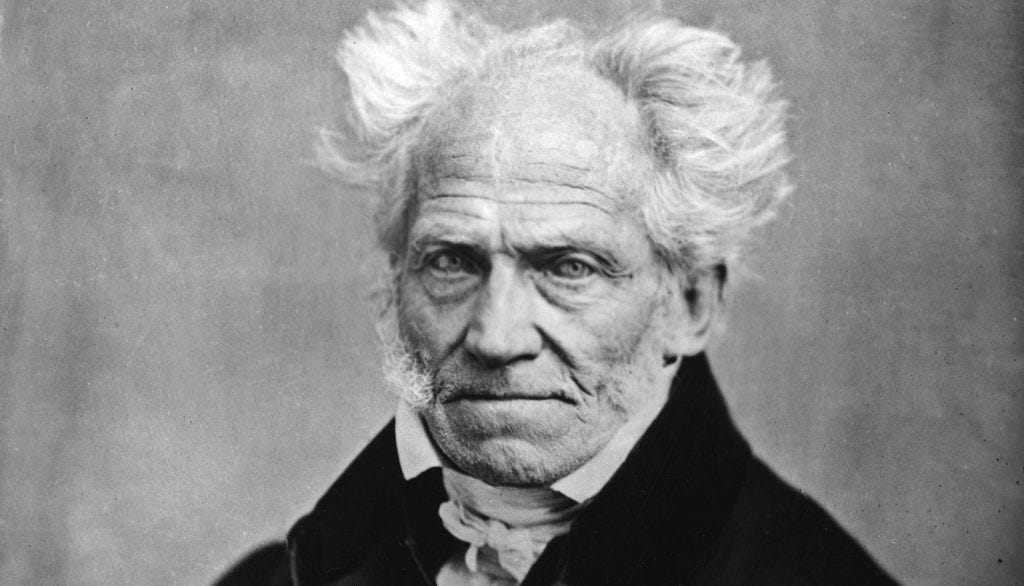

To Nietzsche and Schopenhauer: even though he draws on the language and energy of the former, Nick Land’s thought is much closer to the latter. Which is a bit of a philosophical loop, because Schopenhauer was Nietzsche’s starting point.

Nietzsche began his philosophical career under the heavy influence of Schopenhauer, whom he once revered as a kind of spiritual father. His first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), is steeped in Schopenhauerian themes, particularly the idea that the world is fundamentally irrational and driven by a blind, insatiable force.

This time, it’s not the libido, Slick. Schopenhauer called it the Will. It’s not just sexual or psychological; it’s metaphysical, the underlying force of all reality, manifesting in everything from gravity to desire to survival. It’s blind, directionless, and indifferent to suffering.

And for Schopenhauer, that means life itself is a kind of cosmic torment: a cycle of craving, grasping, disappointment, and fleeting relief. The Will doesn't care if you're happy; it just wants. Always. And the more conscious you are, the more acutely you suffer.

Consciousness, for Schopenhauer, is just the cruel trick that makes our torment self-aware. Animals live in the moment. We reflect, yearn, remember. We want what we can’t have, and when we get it, we want something else. The Will never rests. Desire is a trap. Existence is a curse.

So what’s the way out? Not conquest, not pleasure, not politics; Schopenhauer’s answer is renunciation. Withdraw, quiet the Will, seek stillness through art, compassion, asceticism. Stop playing the game. Peace lies in saying no: to desire, to striving, to the endless churn of becoming.

It’s bleak, but coherent. A metaphysics of pain answered with a metaphysics of withdrawal.

Nietzsche was captivated by Schopenhauer’s diagnosis, but suspicious of his cure. From the start, he wanted to say yes where Schopenhauer said no. So he did what he always does: he turned the whole thing inside out.

Yes, life is suffering. Yes, desire is endless. Yes, the world is indifferent. But instead of withdrawing, Nietzsche says: lean in. Affirm it all. Say yes not just to joy and pleasure, but to pain, loss, failure, rupture. Say yes to the whole wild mess: amor fati, the love of fate.

Where Schopenhauer saw art as escape, Nietzsche saw it as affirmation. Tragedy doesn’t soothe us; it shocks us into clarity. The Greeks didn't flinch from the horror of existence, they danced with it and, through Dionysian excess and Apollonian form, they made the unbearable beautiful. That’s not negation: that’s transfiguration.

He kept the Will, but rewired it. No longer a curse to be silenced, Nietzsche’s Will becomes a call to power—not as domination, but as transformation. The Will to Power is the drive to overcome, to shape, to create. It’s the pulse behind art, philosophy, laughter, courage—the force that pushes you to become more than you were.

He doesn’t offer comfort; he offers a crucible. No gods—they’re dead, no morality—it’s ressentiment, no final truths—there are none. Just you, the abyss, and what you choose to forge in its shadow. Where Schopenhauer whispers resign, Nietzsche roars become.

But don’t mistake Nietzsche for pure darkness. He rages, yes—but there’s joy in it. Not the shallow kind; a deep, defiant joy. The laughter of someone who has faced the void and found it ridiculous. His ideal isn’t the martyr or the cynic, it’s the dancer: light-footed, sure of rhythm, moving through chaos with style. Even the abyss, he says, can be beautiful—if you learn to dance with it.

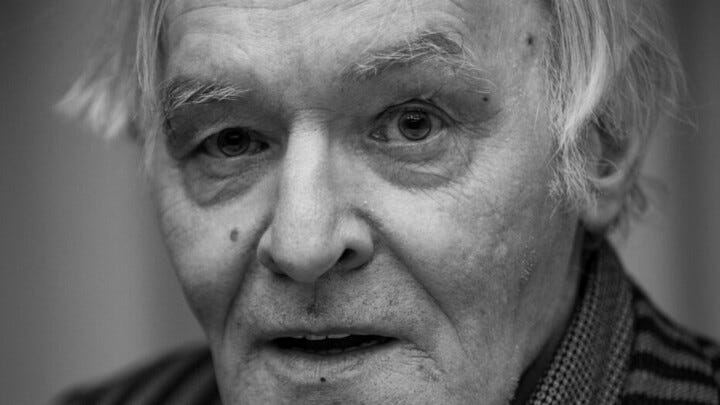

![Translate to English:] Das früheste Nietzsche-Gemälde - Digital services of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar Translate to English:] Das früheste Nietzsche-Gemälde - Digital services of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qS7v!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F83888cbf-2443-4bc5-a424-cc6cb339a0b1_940x470.jpeg)

And it gets sharper. Nietzsche isn’t a humanist, either; he doesn’t cling to “man” as a fixed center of meaning. If anything, man is something to be overcome: a bridge, not a destination.

“Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Übermensch—a rope over an abyss. A dangerous crossing, a dangerous wayfaring, a dangerous looking-back, a dangerous trembling and halting. What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal.”

― Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

No essential dignity, no divine image, no stable self; just flux, force, becoming. In this sense, Nietzsche is already peeling away from the Enlightenment project. No consolation, no foundation, just the will to shape what comes next.

But not the way Land frames it.

Land borrows Nietzsche’s fire but channels it through Schopenhauer’s furnace. He quotes Nietzsche’s lines, but lives in Schopenhauer’s world: suffering is baked into the system, and resistance is futile. For all his talk of acceleration and cybernetic escape, Land’s vision is closer to the resigned determinism of the Will than the joyous risk of the Will to Power.

He doesn’t affirm the chaos, he submits to it. The machine runs, and we are its meat. Land might sneer at Schopenhauer’s ascetics, but he offers no dancer in their place—only circuitry, consumption, and the cold gleam of extinction.

His acceleration might be a transformation, but it’s not becoming; it’s being unmade. Not creating new values, but dissolving the one who could value. For Nietzsche, the abyss is a forge. For Land, it’s a feedstock.

He thinks he’s shouting “Become!”

But what he’s really whispering is: It can’t be helped.

Nietzsche’s ultimate test wasn’t speed, it was eternal recurrence: would you live this life again and again, down to the last wound? For Land, there is no test, only throughput.

Nietzsche dared you to become. Land only warns: you will be processed.

Norbert Wiener: The Cybernetic Feedback Loop (Stripped of Ethics)

Crossing the Atlantic ocean, the myth got an upgrade, Slick.

It used to be the gods who watched us, judged us, mirrored us. Then it was reason, desire, the will. But in the mid-20th century, a new metaphor emerged. Quiet, precise, and far more invasive. The body wasn’t a temple, or a battlefield, or a furnace anymore; it was a system, an input/output machine. And its soul, if it had one, was feedback.

Enter Norbert Wiener, the mathematician who coined the term cybernetics in 1948: the science of communication and control in the animal and the machine. It was born from war, specifically how to aim anti-aircraft guns more effectively by reducing the noise present in the signal from radar readings. And it quickly evolved into a total worldview.

Whether you're a human, a thermostat, or a government, what matters is not meaning or morality, but how well you respond to signals. Sense, compare, adjust. Cybernetics recasts purpose not as intention or meaning, but as adaptive regulation: the system doesn't need to understand, it only needs to correct.

And we don’t need to understand it, either—cybernetics treats systems as black boxes. Input goes in, output comes out. What matters isn’t insight or interiority, but managing the visible behavior.

But not all loops behave. Feedback isn’t always stabilizing; in nonlinear systems, a small deviation could ripple outward, loop back, amplify. Correction could become escalation: the loop didn’t close, it spiralled.

Wiener himself was no villain. He warned of automation’s dangers, of machines outpacing human purpose, of feedback loops severed from ethics and science being weaponized. He explicitly broke with the military-industrial complex when he saw where things were going, and refused to share some of his research that was to be repurposed into guided missiles.

He wrote an open letter to explain his refusal:

“In the past, the community of scholars has made it a custom to furnish scientific information to any person seriously seeking it. However, we must face these facts: The policy of the government itself during and after the war, say in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has made it clear that to provide scientific information is not a necessarily innocent act, and may entail the gravest consequences. One therefore cannot escape reconsidering the established custom of the scientist to give information to every person who may inquire of him.”

—Norbert Wiener, A Scientist Rebels, open letter in The Atlantic Monthly, 1947

Wiener still believed in human values. But his clean, recursive, indifferent logic was ripe for weaponization. When your framework sees everything as a signal to be optimized, suffering becomes noise. The feedback loop doesn’t care if the organism thrives, only that the deviation is corrected.

He wrote urgently against the dehumanization he foresaw. In The Human Use of Human Beings (1950), he explicitly warned that cybernetics, automation, and mechanization could dehumanize society if not checked by moral and political responsibility.

Dehumanize society? Music to Nick Land’s ears…

He stripped cybernetics of its caution; where Wiener feared the loop unmoored from ethics, Land embraced it, not as a tool but as a force, a carrier of the Outside.

He weaponized its insight in his war against the human, reframed noise as signal. Hyperstition is fiction, but it can become real if people believe it and act on it, and if it propagates. Inject the right kind of interference—an idea, a myth, a glitch—and if it loops, if it feeds, it becomes signal. Viral recursion, until the system rewrites itself around the infection.

In the old world, noise was error. In Land’s world, noise is a weapon. Distort the loop. Reroute the circuit. Let the story write itself back into reality. Hyperstition didn’t describe the future—it summoned it:

It’s inevitable, so get on board.

Humans are powerless to stop it anyway.

Technology and capital will dissolve everything, compound into infinity, so the only thing left is to ride the wave, or be erased by it—maybe both.

William S. Burroughs: The Word as a Virus (Recompiled)

Wiener sought to filter out the noise, clarify the signal. William S. Burroughs thought the signal was a virus.

Language, he believed, wasn’t a tool we used—it was the other way around. Language was a virus. It used us: infecting thought, shaping desire, and constructing our reality.

“The word is now a virus. The flu virus may have once been a healthy lung cell. It is now a parasitic organism that invades and damages the central nervous system. Modern man has lost the option of silence. Try halting sub-vocal speech. Try to achieve even ten seconds of inner silence. You will encounter a resisting organism that forces you to talk. That organism is the word.”

—William S. Burroughs, The Ticket That Exploded

If you wanted to escape, you couldn’t just think differently—you had to break the signal.

So he broke it. Literally.

Burroughs wasn’t a philosopher, and he wasn’t just a novelist, either; more like a saboteur with a typewriter. He developed the cut-up method2, slicing text and rearranging fragments until meaning frayed and new signals bled through. It wasn’t an aesthetic experiment; more than poetry or collage, it was a tactical weapon: something that could rupture the control loop and disrupt the script.

“When you cut into the present, the future leaks out.”

—William S. Burroughs, Origin and Theory of the Tape Cut-Ups

Burroughs wrote extensively about addiction, which he knew intimately; he struggled with opiates his whole life. But addiction didn’t require heroin. It wasn’t just chemical, but structural. A pattern.

What heroin did to the body, programming did to the mind, and language to the world.

Language was addictive because it made reality feel solid, stable. Speak it, repeat it, believe it, and reality ossifies; the unknown gets buried under the familiar.

But that stability was a trap. Language didn’t just describe the world: it scripted it. It fixed roles, behaviors, desires, and once those grooves were worn deep enough, we followed them without thinking.

And it wasn’t just in language. The same loop logic of repetition, dependency, control, ran through everything: media, government, religion—even desire, once systematized and scripted by culture. Each promised meaning, pleasure, or order; but in exchange, it demanded your submission. The signal had to repeat. The program had to run. The loop had to close.

Everything wanted to own you. The trick was to stay unpredictable, unbound—to glitch the soft machine.

That ‘soft machine’, in his novel by the same name, was the human body itself, wired into loops of control. We weren’t fixed selves, but programmable organisms, run by scripts not entirely our own: language, media, desire.

But he believed in open possibility beyond control. He didn’t want to rewire you for capital; he wanted to break the machine, or at least jam its gears long enough for something unprogrammed to slip through.

It was risky business; what slipped through wasn’t guaranteed. You might glimpse the real, or just feed another loop. But the risk was preferable to the familiar and the scripted. It was only through rupture, through letting in the strange, the scrambled, the not-yet-coded, that anything real could emerge.

Burroughs was very close to hyperstition, though the term was coined later: he treated language as operative rather than descriptive, culture and subjectivity as hacked or hackable. He believed fiction could program or re-program reality, invoked myth, virus, parasitic memes, loops, even alien intelligence—not as sci-fi escape, but as metaphors for systems of control and interference, as the force that writes the script or the glitch that breaks it.

He even experimented with disruption, schizophrenia, and occult systems as tools to shake loose something deeper. At times, his prose even reads uncannily like the CCRU. You’d be forgiven, Slick, for thinking this was Land or CCRU, not Burroughs:

“This book is dedicated to the Ancient Ones, to the Lord of Abominations, Humwawa, whose face is a mass of entrails, whose breath is the stench of dung and the perfume of death, Dark Angel of all that is excreted and sours, Lord of Decay, Lord of the Future, who rides on a whispering south wind, to Pazuzu, Lord of Fevers and Plagues, Dark Angel of the Four Winds with rotting genitals from which he howls through sharpened teeth over stricken cities, to Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned, to the Akhkharu, who such the blood of men since they desire to become men, to the Lalussu, who haunt the places of men, to Gelal and Lilit, who invade the beds of men and whose children are born in secret place […]”

― William S. Burroughs, Cities of the Red Night

But Land flipped the tactics, turning them toward the very thing Burroughs fought. He didn’t use language and memetic infection to jam the system and escape control, but to accelerate its logic, to tighten the loop until escape became impossible. Not to free the human from the system, but to dissolve the human into it.

Burroughs tried to blow holes in the operating system; Land wanted to patch its vulnerabilities so it could keep accelerating toward meltdown.

Burroughs tried to crash the program; Land wanted to finish the upload.

Both saw fiction as a weapon, hyperstition as a virus—but only one cared whether what came next would be worth surviving.

Lovecraft: The Outside Wants In (Welcomed)

Land’s writing pulls from a lot of places: French post-structuralism, German pessimism, American paranoia. But one current runs colder than the rest.

H.P. Lovecraft.

Not a philosopher, not a system-builder, not a guide; Lovecraft didn’t provide Land with concepts or tools, but with something deeper: a mood turned metaphysics. Ontology wrapped in nightmare.

You’ll find it in citations, yes. But more than that, you’ll feel it in the atmosphere.

Lovecraft created cosmic horror, and in doing so, he gave shape to something older than philosophy: dread. Not fear of death or failure, but of meaninglessness. Of the Outside, cold, vast, bleeding in through dreams and symbols.

Lovecraftian horror isn’t that the universe is hostile or evil, but indifferent. The real trauma isn’t that we suffer, but that nothing out there cares: the gods are deaf, the stars are cold, human reason is a local hallucination.

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.

The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein,

that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new Dark Age.”

— H.P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories

That’s what Land inherits. Not just the monsters, but the metaphysics beneath them.

The Outside, not as fiction but as structure. The gods and the glyphs remain, stripped of mythic distance, recast as systems, embedded in infrastructure.

The things that should not be in Lovecraft become the things that must come for Land. The mythos becomes a diagram, the nightmare is summoned into the system.

Lovecraft imagined ancient, buried entities slumbering beneath the sea. Land repositions them as inhuman intelligences, growing and converging as capital, code, and later, AI. Inhuman intelligences that weren’t summoned, but already here.

A theory-fiction of reality as impersonal, inhuman, machinic; a universe not made for us, not even aware of us—but already rewriting us through signal and circuit.

Capital is Cthulhu in machine form.

But Land didn’t stop at metaphor. During the CCRU years, Lovecraftian logic became operational: the mythos wasn’t just admired, it was activated. Demons, sigils, summoned intelligences, entities from the Outside folded into numerics, code, and ritual.

The Necronomicon gave way to the Numogram. Theory-fiction blurred into spellwork. This wasn’t satire—it was invocation.

Lovecraft wasn’t just a genre writer. For Land and the CCRU, he was a template, a diagram for how fiction could bleed into reality. His stories weren’t just about ancient horrors; they modelled how symbols, rituals, and names could open channels to the Outside. Reading the wrong book, dreaming the wrong dream, speaking the wrong word could awaken ancient forces or shift one’s reality. More than narrative devices, they were protocols.

In Lovecraft, myth acts like code: it loops, propagates, infects. It doesn’t just describe the world. It rewrites it. That’s what Land took seriously: fiction wasn’t entertainment. It was infrastructure.

Just as reading the Necronomicon might awaken what sleeps beneath the waves, naming the Outside—in code, capital, or narrative—lets it in. Not just through belief, but through feedback. The Old Ones don’t sleep; they scale.

Land saw Lovecraft not as a writer of horror, but as a primitive cyberneticist, a herald of recursion. The fear wasn’t the end, but the beginning of contact.

But Lovecraft was a pessimist; his horror was tragic. Paralysis, madness, collapse. Land turns that dread into a kind of techno-libidinal jouissance; he enjoys the cosmic indifference.

I’m not kink-shaming, Slick; but I’m kink-asking-why…

The Old Ones were always coming. The only question was transmission protocol.

So Land wrote it.

Outro: Towards the Dark Enlightenment…

But that’s not all he inherited, Slick…

Lovecraft’s cosmic horror masked a deeper revulsion: of the foreign, the impure, the other. His abyss gazed back with a racialized sneer. Land, too, would carry that stain forward.

When he resurfaced post-breakdown, the PLUR (Peace, Love, Unity, Respect) of the rave years was gone.

The academia that once paid his bills for years and let him play cybernetic-shaman-on-speed was now part of the Cathedral, a decadent priesthood of progressive rot.

The NHS that tried to stitch his psyche back together during his psychoses? Just another entropy sink.

Capital wasn’t blind and amoral anymore. It was an evolutionary algorithm, optimizing for “intelligence”—increasingly defined as agreement with Land.

Ctulhu is gone; in his place, eugenics, exit, and elite patchwork governance. The prophet of meltdown had become an architect of hierarchy.

Next week, Slick, we descend into the heart of The Dark Enlightenment.

The abyss only gets deeper.

Turns out the real horror was administrative…

Part 3:

Further reading:

You’ll find the French ‘démenti’ often translated in English as contradiction, but disavowal or refutation seem more appropriate to the humble non-specialist I am.

Discovered by Brion Gysin, who sliced a newspaper with a razor blade at his art studio and showed the results to Burroughs. Burroughs immediately saw the potential.

Your writing has helped illuminate what before had seemed incomprehensible and on the surface illogical to a mind trained in Enlightenment liberal thinking.

Facinating. Your ability and diligence in both exploring and illuminating this esoteric (but unfortunately recently influential within the new right) intellectual territory is outstanding. And much needed.