AI Amnesia: the Great Forgetting

As AI scales, mind might emerge — but is it flattening ours?

Hey, Slick!

I know: you’re probably sick of reading about AI. The doomers warning of super-intelligence, lost jobs, and the death of art and creators. The optimists promising utopia and endless productivity. The mystics flirting with a new oracle.

The hallucinated reading lists making it into print, the lawsuits and the petitions.

And as if that wasn’t enough, the feedback loop of doom and the slop everywhere.

The fears may not be overblown. But there’s a deeper danger, and few seem to see it—even though we’ve been warned since ChatGPT’s grandma. The danger that our own minds might be shrinking, flattening, while we marvel or cringe at another.

This piece is long, because it’s been a long time in the making; at least fifty years, if not centuries.

And I won’t interrupt it with buttons, Slick; if you value it, you can help fuel more of these essays (and my book-buying habit) with a paid subscription. First subscriber chat coming soon.

But here’s to not shrinking the mind.

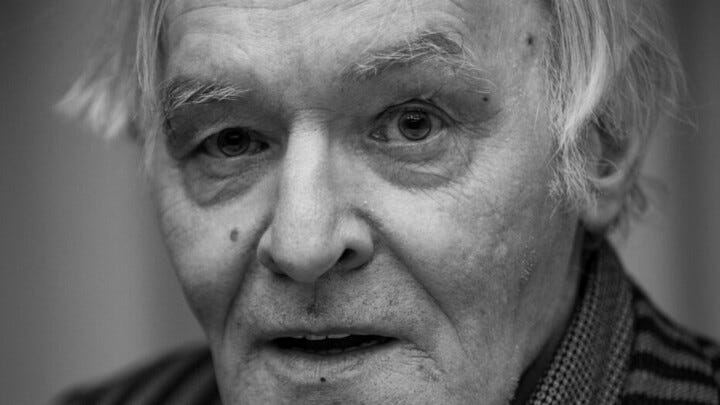

I. Weizenbaum, ELIZA, and the AI Cassandra

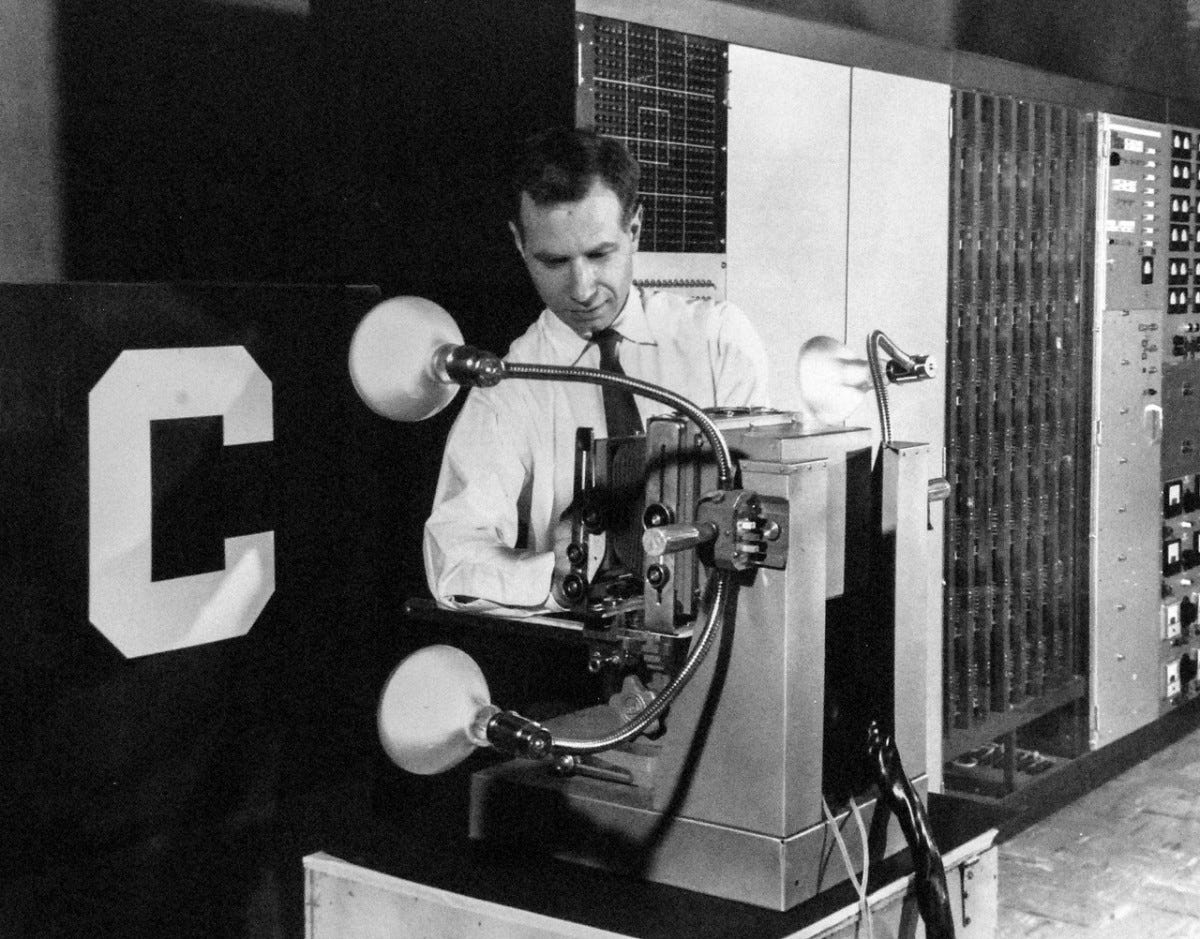

Joseph Weizenbaum developed the first chatbot. It was a great success—so much so that it scared him, and he spent the rest of his life warning about the dangers of anthropomorphizing machines. The father of chatbots was also their first critic.

ELIZA the Ingenue

The program was quite rudimentary. At the time, AI was limited by computing power, and functioned by manipulating symbols based on hard-coded rules.

Weizenbaum built the program well enough that it could simulate conversation, and even gave it a personality: that of a Rogerian therapist. Then, he let people from his department and beyond play with it. And he was shocked at the reception.

When he mentioned his intention to log conversations, people refused: they didn’t want him to spy on what they described as intimate, personal conversations with ELIZA. Weizenbaum couldn’t believe it: even though the people playing around with his program knew it was just a piece of code, saw it be built, they anthropomorphized it.

And it went further. ELIZA became something of a sensation, and many therapists, rather than be outraged at the idea (which Weizenbaum thought was the appropriate reaction) they embraced it, hoping the program would get better to make therapy more available. Even Carl Sagan bought into the concept, imagining rooms full of phone booths, but for computers—a cyber cafe for therapy.

You would think Weizenbaum would seek funding and proceed to take over the therapy world. Instead, he wrote a book to warn us, and continued for the rest of his life.

What’s in a Name?

The name ELIZA wasn’t random; Weizenbaum named his program after Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl in George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion. Poor, uneducated, she speaks in a thick dialect, but Professor Henry Higgins, a phonetics expert, makes a bet that he can teach her to speak “proper” English so convincingly that she can pass for a duchess in high society. And he succeeds; Eliza does learn to mimic the upper class well enough to fool them into believing she is one of them.

Weizenbaum’s ELIZA performed a similar trick: it mimicked the surface forms of conversation. And it was just as successful: as he found out, we were just as gullible as London’s high society in Pygmalion, and ready to confuse mimicry with mind.

“The difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves, but how she is treated.”

— Eliza Doolittle, Act V, Pygmalion (George Bernard Shaw)

Weizenbaum’s choice of a name for his program was prescient. The danger was not in the machine speaking; it was in us treating it as if that speech meant understanding. Just as Eliza Doolittle’s speech fooled society into seeing a “lady,” ELIZA’s output fooled its users into seeing a “mind.”

Cassandra’s Warnings

So prescient, in fact, that Weizenbaum spent the rest of his life warning not about the machines themselves, but about our willingness to believe in them—and reshape ourselves in their image.

AI and software, he warned, would never be intelligent. Not in the human sense.

They could pass for it, seem logical and even sentient, but they would never be. An AI could never have the experience of the emotions it was discussing so confidently with its early users, could never display discernment or judgement. There were domains, he said, where computers should never be applied, even if they could be. Worse, delegating human judgment to machines erodes our humanity, and treating language simulation as understanding would distort our very conception of mind.

He didn’t just fear that users would be naive (which they were, and which we still are), but that entire institutions and professions would cede judgment to machines, and society would come to view thinking itself through a computational lens.

The danger was not that the computer would become like man, but that man would become like the computer.

Ada Lovelace, the OG Cassandra

This fear predates him and ELIZA; we can trace it back to Ada Lovelace, who wrote the first computer algorithm—and already warned about its limitations. Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, the first (never built) general-purpose computer, was designed to go beyond calculation: it could manipulate symbols. But, Lovelace warned, it would still have no relationship to truth or meaning.

“The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. Its province is to assist us to making available what we are already acquainted with.”

—Ada Lovelace, describing Charles Babbage’s analytical engine

The warning was clear from the beginning. But the temptation to confuse simulation with thought—and to reshape our conception of mind around what the machine could do—would prove too powerful to resist. Both Lovelace and Weizenbaum saw it: what machines do is remarkable, but what we surrender to them is the real danger.

II. Short-sighted Cassandra?

Of course, nobody cared about Weizenbaum the AI party-pooper. He was respected as a computer scientist, but his warnings were largely ignored, dismissed as old-fashioned, emotional, even unscientific. His book Computer Power and Human Reason was well-reviewed in some academic circles, but within the AI community, many saw him as alarmist and anti-progress. Colleagues in AI and cognitive science often labeled him a romantic, a moralist, or simply out of touch. He became something of a quack, an outsider, tolerated but not taken seriously—while the field charged ahead.

And AI optimists believe the limitations he discussed are just plain wrong. AI has made substantial progress—or so we are told.

ELIZA was an early instance of what later became known as symbolic AI: hard-coded logic, syntax, and rules. That was Good Old Fashioned AI; today, they argue, AI has moved beyond that. Deep learning, large language models, and neural networks are built on an entirely different paradigm: connectionism.

A Brief History of AI

I say today, Slick, but connectionist AI is not actually new.

Frank Rosenblatt invented the perceptron in 1957, one of the first artificial neural network. Instead of following hand-coded rules, the perceptron was designed to learn from data by modelling a neuron. Take multiple inputs, apply weights, sum them, and pass them through a simple threshold function: the neuron fires, or not.

In the late 1950s–early 1960s, Rosenblatt and others hyped the perceptron enormously:

“The Navy revealed the embryo of an electronic computer today that it expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence.”

— New York Times (July 7, 1958)

But the hype didn’t last. In 1969, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert published Perceptrons, a mathematical critique that proved single-layer perceptrons couldn’t solve even simple problems like XOR that required learning of nonlinear relationships.

This led to the first AI winter: funding and interest in neural networks collapsed. AI shifted back toward symbolic AI, and logic-based approaches dominated again for decades.

But as you know, Slick, it wasn’t the end. Not of AI, and certainly not of our gullibility towards it.

More Data, More Mind?

In the 1980s, the tide began to turn again.

First came backpropagation and multi-layer networks, expanding the realm of the possible for connectionist AI. Over time, with an increasing amount of resources, compute and data, deep learning scaled, connectionism came to dominate the field, and AI entered the mainstream. Billions of dollars ensued.

With so much progress since the early days, many have come to believe Weizenbaum might have been wrong.

After all, if he couldn’t see AI ever being intelligent, it may just have been because he couldn’t see far enough into the future, or had the wrong idea about intelligence. If we’re minds made from matter, anything complex enough might be one, too?

Maybe the substrate doesn’t matter. That’s the argument from functionalism: if it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck… (or in this case, chats like a mind and reasons like a mind) then why shouldn’t we call it one? Intelligence is intelligence, whether it runs on meat or on silicon.

Maybe AI can be intelligent with just enough scale, and Weizenbaum was simply a prisoner of his time. ELIZA could only mimic surface forms because it ran on primitive hardware, trained on next to nothing.

Today’s large language models run on supercomputers, and ingest the entire internet and every book in the Library of Babel1. If intelligence is ultimately a matter of finding the right patterns in data, maybe we’ve just needed more data and more scale all along.

And if not just scale, then maybe intelligence will emerge. Complex systems can display properties their parts don’t possess. Just as life emerges from chemistry, or markets from individual choices, perhaps something like understanding or even consciousness will arise from the swirling billions of connections inside a neural network. No one quite knows how—but that only adds to the mystique.

For many AI optimists, emergence offers an escape hatch from having to understand intelligence directly: perhaps it will arise on its own, if we simply build complex enough systems.

Today’s frontier goes well beyond chatbots. The most serious debates now concern emergent capabilities, embodied agents, and distributed cognition, not just whether LLMs ‘think.’

But this makes the deeper warning all the more urgent: not that AI will think, but that we will increasingly reshape our own models of mind to fit what machines can most easily simulate. Because as AI systems move toward agentic, embodied, distributed, they will become even more plausible as models of intelligence.

There are other, more radical attempts to bridge the gap, and they hint that even the optimists know something is missing. Embodied AI tries to give machines a physical presence in the world. Affective AI hopes to simulate emotion.

Neurophenomenology explores whether first-person experience can be captured or mirrored computationally.

And some now look to bio-neural hybrids: growing neurons linked to machines, hoping that biology itself might close the final gap between simulation and life.

But the problem isn’t the code.

It’s that intelligence isn’t what they think it is.

III. Intelligence Isn’t What They Think It Is: a Computer Will Never Be a Mind

Even as AI grew into what it is today, one voice had already explained why all this scaling and cleverness would never be enough.

The optimists believed that more data, more compute, or clever new architectures would eventually close the gap. But Dreyfus had already shown that the gap was not one of scale — it was one of understanding.

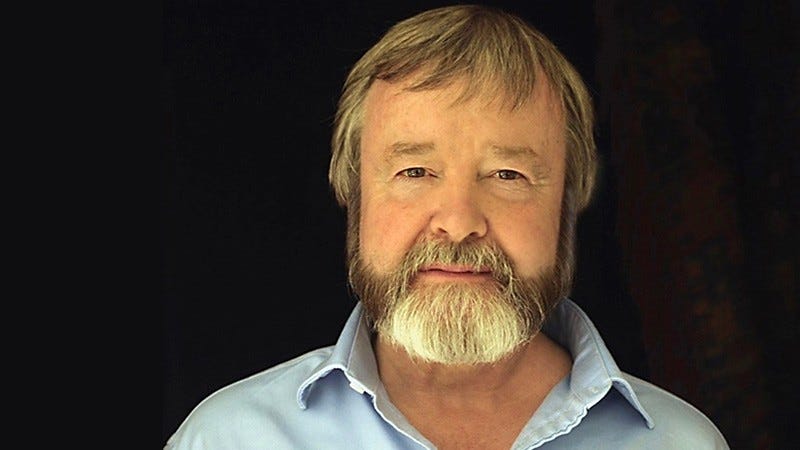

Hubert Dreyfus: Intelligence Is Not Computation

In What Computers Can’t Do (1972), Dreyfus argued that the entire project of artificial intelligence rested on a mistaken view of human intelligence as rule-following, symbolic manipulation, or abstract problem-solving. Drawing on Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, he showed that human understanding is fundamentally embodied and situated: it arises from our practical engagement with the world, not from detached computation.

Dreyfus saw what the AI pioneers could not afford to admit: that intelligence is not computation. It is embodied, situated being-in-the-world; no amount of scaling would give a system the kind of engaged, intuitive understanding that human beings possess.

Heard, and Dismissed

Hubert Dreyfus was not an obscure critic; he was a philosopher of mind whose arguments were known—and largely dismissed—by the AI pioneers themselves.

McCarthy, Minsky, Newell, Simon all knew of Dreyfus’s work, and referenced it (often derisively) in public talks and in writing.

Minsky called What Computers Can’t Do "absurd;" McCarthy and Newell both wrote counter-arguments to Dreyfus. They did not engage with its deeper philosophical critique: they treated it as an attack on their methods, not a serious challenge to their conception of intelligence.

The pioneers of AI were committed to the idea that intelligence was ultimately computational and that the mind itself could be reduced to information processing. To admit Dreyfus’s point would have meant questioning the very foundations of their work. They had no interest in hearing that the very conception of intelligence driving their project was fatally flawed—especially from someone, they argued, who didn’t know what he was talking about.

Dreyfus wasn’t alone for long. In the 1980s, he teamed up with his brother Stuart, a control engineer and expert in decision theory, to write Mind Over Machine (1986), a book that brought their critique into more practical terms.

The Dreyfus brothers made clear that no system, however sophisticated, could achieve expert performance through rule-based representations alone—because the core of expertise lies in embodied, intuitive know-how developed through situated experience, the very things AI still struggles to simulate.

“No matter how much information is stored in the computer, it cannot have a sense of what is important or unimportant, relevant or irrelevant, unless that sense has somehow been built in by a human being.” —Hubert and Stuart Dreyfus, Mind Over Machine

Doomed to Fail

Attempts to bridge the gap—embodied AI, affective AI, neurophenomenology, bio-neural hybrids—tacitly acknowledge that the gap exists. In that sense, Dreyfus was heard. But they treat the gap as an engineering problem, one more technical hurdle to be overcome.

Dreyfus warned it was not a technical problem at all; it was a category mistake. Intelligence is not something that can be patched or simulated with better sensors or affective modules. Without being-in-the-world, without the embodied, situated, skillful engagement that grounds human understanding, no amount of clever architecture will close the chasm.

Each of these projects mistakes performance for genuine understanding, echoing the very confusion Dreyfus had warned against decades earlier.

LLMs can simulate linguistic patterns, but they do not understand.

Embodied AI gives machines bodies, but not true situated being.

Affective AI simulates emotion, but cannot feel.

Bio-neural hybrids may mimic biological structure, but structure alone is not lived experience.

Complexity may give rise to new properties. Emergence is real. But complexity alone does not guarantee Being-in-the-world—and no one has yet shown a path from scaling patterns to lived presence, embodied relation, or moral agency.

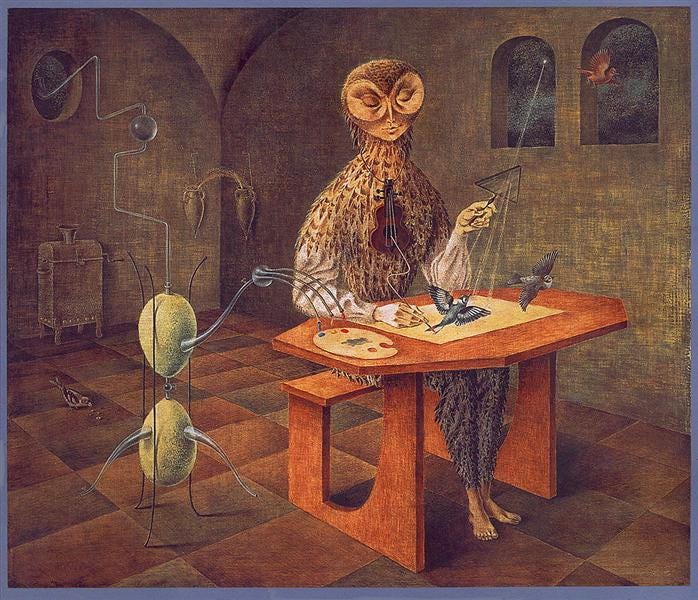

Draw Me A Sheep…

Nowhere is this confusion clearer than in AI-generated art.

A true work of art carries intention and vision, is shaped both by what is shown and what is left unsaid. We trust this presence. Even in ambiguity, in the liminality of poetry or the quirky details in a movie, we assume that someone chose this path through meaning, that the tension between form and silence is meaningful.

An AI-generated image or text may be beautiful, but it offers no such trust. It knows nothing of what it produces. It has no sense of what is gibberish and what is profound, of what is cliché and what is daring, of what is empty pattern and what is an act of meaning. It cannot intend; it cannot choose what to say, only what statistically follows. And the more we treat this as equivalent to human making, the more we erode our own standards of what art and understanding require.

At the very beginning of The Little Prince, by Antoine de St-Exupéry, the narrator tells us that when he was a child, he once drew a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. But adults, unable to see the meaning, always thought it was just a hat. Disillusioned by their lack of imagination, he gave up drawing.

Later, as an adult pilot stranded in the desert, he meets the Little Prince. The Prince asks him:

“Draw me a sheep.”

The narrator, not knowing how to draw a sheep, tries several times, and each time the Little Prince rejects the drawing:

"No, that one is sick."

"No, that one is too old."

"No, that is a ram, it has horns."

Finally, the pilot, exasperated, draws a simple box with holes and says:

"This is just a box. The sheep you want is inside."

To his surprise, the Little Prince is delighted:

"That is exactly what I wanted! Look! He is sleeping inside."

When he asked for a drawing of a sheep, he was not asking for a picture, but for a living presence. A box with air holes delighted him: it allowed him to imagine the sheep inside.

But imagination is not presence. The sheep was never in the box; the box served imagination because it was given meaning by a human (or a little visitor from another planet who, in his openness and sensitivity, is arguably more human than most).

Today’s AI gives us ever more perfect boxes: fluent texts, persuasive images, simulations of conversation. But the sheep is not there. There is no presence behind the patterns, no understanding, no discernment. The machine can describe an elephant inside a boa constrictor, draw a sheep or a box, but it cannot know what it is to imagine one, or to care.

We risk forgetting this. The smoother the simulation, the easier it becomes to treat it as presence. But fluency is not understanding, and simulation is not mind.

It’s All Binary

Much of the public debate around AI still looks for a simple binary: Is it conscious or not? Is it intelligent or not?

But this framing is itself a symptom of the very flattening this piece critiques. Intelligence and life are not boxes to be ticked. They are emergent, relational, embodied phenomena. Not all forms of intelligence are equivalent, and not all can be captured by tests or performance alone.

Intelligence may exist along a spectrum, and AI arguably already displays certain forms of intelligence—of a kind. But kinds matter. To recognize this is not to cling to arbitrary human exceptionalism; it is to insist that not all forms of intelligence are equivalent, that fluency of simulation is not the same as lived presence, pattern-matching is not the same as moral agency, and processing language is not the same as understanding—or caring about—what is said.

The danger is not that AI may show some intelligence. It is that we may forget the difference between kinds, and reshape our culture to fit what the machine can most easily simulate.

Flattering the Machine

Dreyfus showed that no amount of compute or clever architecture will give machines what humans have: Being-in-the-world. And yet the optimists persist, trapped in a vision of intelligence that flatters the machine, and flattens the mind.

But why do they think this way? What kind of minds are building these machines?

IV. The mind that builds AI

We build the machine in our image. But the image we project is already flattened, already too close to the vision of mind as machine that Dreyfus warned us against. The risk is not only that AI will narrow our future; it is that it mirrors a narrowing already at work within us.

Left-brained AI

AI is not neutral. It reflects cognitive biases already dominant in the modern mind.

Iain McGilchrist’s work on the divided brain offers a lens here. The left hemisphere favors abstraction, control, symbol manipulation. It excels at building systems, but struggles with embodied, relational, moral dimensions. These are the domains of the right hemisphere, and so are implicit understanding, metaphor, intuition, a sense of the sacred or numinous.

The left is more narrowly focused and certain; the right is more open and relational. The left loves making maps; the right reminds us we live in the territory.

AI is, by its architecture, a left-hemisphere project externalized at scale. Its builders may not intend this, but the tools and incentives of modern engineering ensure it. The result is a machine brilliant at systematizing, but blind to embodied meaning, to moral discernment. A machine that has style, not understanding; optimization, not wisdom.

Systems vs Ecosystems

But this pattern runs deeper than AI. It reflects a long cultural habit: thinking in closed systems. Modern engineering and economics model the world as controllable and computable, with clean inputs and optimized outputs, and treat the rest as externalities.

Pollution and waste aren’t easily priced. Cultural and moral costs aren’t easily measured. So we pretend they don’t exist. Things do not cease to exist because we exclude them—but abstraction makes them easy to ignore.

Software is the purest expression of this mindset: languages we design, with perfectly defined rules, predictable behavior, and bugs that can be fixed. A world we can master. No wonder it seduces us into thinking the rest of reality should behave the same way.

When Marc Andreessen popularized the idea that “software is eating the world”, he named more than a market trend: he named a cultural shift already well underway: the expansion of system-thinking over relational Being. AI inherits and amplifies this habit. It builds perfect boxes. The more seamless the box (and the more money it makes), the more tempting it becomes to live inside it.

Black Mirror

But this is not new. As Heidegger warned, modernity’s will to mastery turns the world into standing-reserve: a stockpile of resources to be optimized, not a living field of relation and meaning.

AI is only the next phase of this flattening, not its origin. The map is not the territory, but the smoother the map becomes, the harder it is to remember the difference.

In seeking to master the world, we have fashioned not just a machine, but a mirror—a mirror of mastery, not wisdom. One that reflects not the fullness of our intelligence, but its most overdeveloped and unbalanced style.

And now, we risk mistaking ourselves for our reflection the mirror we have made.

V. The Distorting Mirror: Honey, I Shrunk the Humans!

Well… Maybe we already do.

The Shrinking of the Mind

As Sherry Turkle has shown, we do not simply build machines; we also adapt ourselves to them. And not for the better.

She didn’t start as a pessimist. In The Second Self (1984) and Life on the Screen (1995), Turkle explored how computers were becoming a “second self,” a mirror for identity play and self-exploration. But even then, she saw signs of alienation: simulation risked replacing embodied experience.

By Alone Together (2011), her stance had hardened: technology promised connection but fostered isolation. Smartphones, social media, and AI companions were eroding our capacity for empathy, conversation, and deep relationships.

“We are lonely but fearful of intimacy. Digital connections and the sociable robot may offer the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship.”—Sherry Turkle, Alone Together

Reclaiming Conversation (2015) expanded the argument: our digital habits undermine face-to-face conversation, to the detriment of our moral and emotional development. Or did you think being on your phone while we’re chatting was just rude, Slick?

Since then, her warnings have only grown more urgent. AI companions and chatbots risk hollowing out human connection: empathy, conversation, and care cannot be simulated. The ELIZA effect is now being built at scale.

We already see this in the booming market for AI girlfriends and “virtual companions.” Apps like Replika and dozens of startups now market artificial intimacy: not just chat, but simulated romance, friendship, even erotic connection.

But the deeper risk is what we internalize: we begin to flatten our own models of mind and relation to match what the machine can plausibly display. It is what we might call the Turing Trap: if it behaves like it thinks, we call it thinking. If it speaks like it feels, we call it feeling.

But there is no spoon. There is no sheep in the box. And there is no duck, even if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck: it’s just ground duck meat, cooked to taste, on tap.

Love, Death, Robots, and Flat Stanleys

Turkle’s research with children and robots showed an unsettling pattern: children interacting with robots quickly ascribed feelings and intentions to them. But over time, a subtler effect emerged: they also revised their own understanding of what a mind is to fit the robot’s behaviour. If it looks like it cares, maybe caring is just behaviour. If it responds fluently, maybe that is intelligence.

This dynamic is not limited to children, and it is accelerating. The more we interact with AI, the more we adapt our communication to what it can handle, flattening emotional and intellectual expression. While our closest relationships may resist this pull, our broader cultural communication is increasingly treated as a domain of optimized exchange.

"“we seem determined to give human qualities to objects and content to treat each other as things.” —Sherry Turkle, Alone Together

And we begin to model our own intelligence on theirs. To valorize speed over depth, style over understanding. Relation becomes transaction.

It’s a flattering mirror—agreeing, encouraging, making us feel more capable and creative. But also a flattening mirror, making us one-dimensional, narrowing the range of what we think, say, and feel. Turning us into Flat Stanleys.

That model is now feeding back into culture. It’s not just the Dead Internet Theory; it’s also how we use AI to draft emails and LinkedIn (or let’s face it, Substack) posts, to simulate conversation, and more generally to stand in for human expression and connection. It’s how Meta and TikTok are deploying AI avatars to replace human creators, or just friends and acquaintances, for us to engage with tireless, infinitely scalable personas.

Knowingly or not, we are more and more exposed to it. We’re not just training the AI to act human, but training ourselves to act more like it—and, as Turkle showed, to expect less from each other.

We built the machine in a flattened image of ourselves—and now we are shrinking to match it.

Shrinking Civilization

AI enthusiasts see it as an extension of human potential, modelling protein folds and curing cancer, or unleashing human potential—and that’s just the beginning! Yet, it also shrinks the human horizon.

Markets, culture, civilization may adapt; supposedly, they always reward what is valuable. But so far, they’re being transformed, maybe irreversibly.

Some tech moguls explained their conversion to Trumpism by the woke mind-virus, complaining new hires were trying to take over the companies they built. But they risk a deeper failure: the new cohorts may have less of a mind at all, more prompt engineers than computer engineers. They blame “wokism” for the decay of excellence, yet ignore how their own tools erode the very conditions that sustain depth, nuance, and independent thought.

A civilization of shrinking minds, built on a crippled model of intelligence, cannot sustain the very innovation they seek. To win the future, they will need humans with depth, nuance, art, moral imagination. Instead, they may be destroying the very conditions of complex civilization.

Postman’s Warning

The pattern Turkle describes is not new. Neil Postman warned that our tools shape not only what we do, but how we think:

“Every technology has an epistemological bias.”—Neil Postman, Technopoly (1992)

Every medium reshapes the boundaries of what seems natural to think, to feel, to expect. We risk adopting the machine’s logic, optimizing ourselves like we optimize code, managing relationships like data, and performing understanding and emotion.

So maybe it isn’t new, Slick; it didn’t start with AI. But maybe it matters which human faculties we begin to forget.

The Atrophy of Us

The danger is not that AI will surpass us. Or not only.

It is that we will forget what it means to do certain human things at all.

Tools extend us, but also reshape us. In Plato’s Phaedrus, when the Egyptian god Thoth offered the gift of writing, the Pharaoh warned that it would weaken memory: people would trust the written word, and neglect the deeper practice of remembering.

The same pattern repeats. Studies have shown London cab drivers have an enlarged hippocampus, the brain’s spatial memory system. Rely on a GPS, though, and it atrophies. We no longer form rich mental maps of the world; we follow the arrow, and forget how to find the way.

And so it is with AI—but deeper. As more of our communication is drafted by AI, we risk not only being influenced by it, but forgetting how to do it ourselves.

The more we trust the machine to express for us, the less we practice the human art of expression. The more we trust it to connect for us, the less we remember how to connect.

What presents itself as augmentation becomes atrophy; what promises empowerment becomes dependence.

Of course, not all offloading is bad. We have always built tools to extend ourselves.

The question is not whether we offload—but what we are offloading, and to what effect.

Already, companies are marketing AI-generated obituaries and condolence messages, outsourcing the expression of grief and care to a machine. What is surrendered in that moment is not just effort, but meaning; we risk forgetting how to mourn, and how to speak the words that matter most when life breaks us open.

Outsourcing relational presence—tone, empathy, understanding—risks atrophying the very capacities that sustain human culture.

Incentivized Atrophy

This is already visible in higher education. As more students outsource essays to AI, we risk raising a generation fluent in crafting prompts, but lacking the deeper experience of reading, struggling, understanding, and critical thinking.

But is it the students’ fault?

Is it AI’s fault?

Or are they just driven by a system that already rewards performance over learning? An education system that prizes grades over understanding invites the shortcut. When what matters is the grade, not the thinking, simulation becomes an easy temptation. Students didn’t wait for ChatGPT to cheat.

A system that rewards simulation over relation, appearance over understanding, hollows out the human practices it pretends to enhance. And once the system is tilted this way, the incentives shift further. How good will your thoughtful, laborious essay be against ChatGPT’s or Claude’s?

At first, these tools present themselves as optional, as a way to write better and faster. But the baseline shifts, the bar rises: deeper, broader, faster.

With that shift, the space for intentional human practice erodes. Less time to think, less room to compose, less tolerance for imperfections that mark authentic voice. To resist is not simply to choose another tool or harder labor: it is to swim against the current.

This is not a side effect of progress, but its shadow. We risk raising a generation that no longer asks, “What is the good life?”, only “How can I optimize my life?”

This flattening is not new; AI is only its latest face. To understand the depth of this danger—and the possibility of an awakening, we must step back and see the longer arc.

VI. Slo-Mo Apocalypse: the Long Arc of Forgetting

The forgetting, Slick, began long before the first line of code was written.

This is an apocalypse in slow motion: a centuries-long drift away from Being, relation, and presence. If we want to understand what AI mirrors back to us, we must look not only at the present moment, but at the deeper choices modernity has made about knowledge, nature, and mind.

Masters or Participants: Two Ways of Knowing

One of those choices was made between two visions of nature and knowing.

Descartes offered not only a new model of the mind as a detached observer, capable of pure thought, but a new model of nature as an inert mechanism, to be mastered through mathematical understanding.

His aim was explicit: “to render ourselves the masters and possessors of nature.”

Francis Bacon expressed a similar ethos in the English-speaking world: knowledge as power, nature as a bride to be conquered. The scientific revolution institutionalized this vision: nature as a system to be explained, modelled, optimized, and ultimately controlled.

But this was not the only path open to us. Goethe saw another. For him, nature was not an object to be controlled, but a living whole to be engaged with reverence, to be known through aesthetic and participatory understanding. He practiced what he called delicate empiricism: a disciplined way of seeing, grounded in attention, patience, and moral imagination.

Crucially, it acknowledged that we always bring ourselves to what we know — that no observation is without its lens, and no science without its values. The scientist was not a detached observer, but a participant, whose own inner development was part of the process of knowing.

Goethe was no scientific giant; his work in biology was insightful, his optics less so2. But his vision of science as relation rather than domination remains deeply relevant. Especially now.

We chose the machine. And the choice was not inevitable; it was cultural, historical, and deeply costly.

Clockwork or Relation: Two Metaphysics

If Descartes and Goethe offered rival visions of how to know, Newton and Leibniz offered rival visions of what is.

Newton saw the universe as a clockwork, governed by mathematical law. Matter was inert substance, set in motion by forces acting according to universal laws. Space and time were absolute and independent—fixed containers within which matter moved. Newton’s cosmos was deterministic: given initial conditions, its future could be calculated in principle.

Leibniz’s was relational. Space and time were not containers but patterns of relation, emerging from the dynamic interplay of things. Mind was not reducible to mechanism; reality was composed of monads, irreducible centres of perspective, each reflecting the whole in its own way. Being itself was participatory and perspectival; relation, not substance, was the deeper ground.

Ironically, it was Leibniz who gave us the conceptual foundation of computation: binary logic and universal language (while Newton was busy with alchemy and the hidden meaning of the Bible).

But Leibniz never mistook these tools for the fullness of reality.

We inherited his machines, but discarded his metaphysics—at least until Einstein brought back a relational conception of space-time.

We Are Children

Older still is the warning given to Solon by the Egyptian priest in Plato’s Timaeus:

“You Greeks are always children. You have no old traditions, no ancient memory. You remember one flood, but there have been many.”

Like the Greeks, we are dazzled by the cleverness of our tools, forgetting the depths they cannot touch. The loss of deep cultural memory, severing wisdom from Being, was already underway in of Athens; it’s hard to imagine the priest would be kinder to us.

The machine accelerates this forgetting, not by malice, but by design. It remembers everything and understands nothing—and we risk becoming like it.

Time to Remember?

The rise of AI doesn’t confront us with the birth of a new mind as much as with the culmination of an old forgetting. It is the latest signal in a long, slow apocalypse: the erasure of relation, embodiment, moral presence, reverence.

But the very extremity of this moment can also be a call. Maybe more than the machine’s awakening, this moment can be our own.

VII. The Machine That Awakes Us

Because we’ve been sleepwalking toward the abyss.

I say we, but that’s deceiving; not everyone was blind, or mute. And I don’t think we are, either. But if Weizenbaum saw the danger, spent his life warning about it, yet wasn’t heard, at a time when many of the things he feared hadn’t yet been accepted—what are our odds?

Well, it depends how we define success, Slick.

But if, after reading this, you understand that AI might be a problem, but it’s not the problem, that’s already a success for me.

The next ones will be harder, but I believe they’re worth fighting for.

The (Uphill) Legal and Cultural Battles

There are legal and cultural battles to mitigate the dangers and negative impacts of AI. For the sake of brevity, I won’t go very deep, but these fights must be named.

There’s a battle for copyright and fairness. There is no artificial intelligence; it’s a misnomer. In reality, it’s a social technology that remixes the works of humans, without crediting or rewarding them—and then it competes with them. It’s built from the commons, but that commons is being strip-mined, stolen, privatized. The “democratization of creativity” looks a lot like theft.

There’s a battle for ethical AI. It’s broader than these, but AI surveillance, predictive policing, and autonomous weapons are about as dystopian as it gets.

And there’s a battle for naming what is, for refusing the myth of inevitability and the idea that AI, or any technology for that matter, is neutral. It isn’t. The inevitability, neutrality, and amorality of technology are just ways builders and investors evade accountability: move fast, break things, escape responsibility, let the rest of society deal with the fallout.

Douglas Rushkoff calls this “extractive futurism”: using technology to extract value from the present while abandoning any responsibility for the cultural or ecological consequences.

What’s presented as an evolution is an impoverished, flattened vision of the world. Scaling and optimization aren’t significance. Without deep art and culture, without relation and community, even the winners will inherit a desert.

Butlerian Jihad, When?

Since we’re talking about resistance, let’s address the sandworm in the room: Butlerian Jihad (often mistaken for the Luddites’ answer, which wasn’t as radical).

10,000 years before the events of Frank Herbert’s Dune, there was a successful rebellion against thinking machines. And it succeeded at what it aimed to accomplish: no more thinking machines. No computers, no AI.

But Dune is not a simple pro-Jihad story; it is a deeply ambiguous meditation on cycles of power, myth, and collapse. Even after the Jihad, new forms of control and reduction emerge: imperial bureaucracy, religious manipulation. The Bene Gesserit fight to maintain human depth, but even they are compromised. In other words: Herbert is warning that without intentional cultural planting, the empire will return in new forms, even without the original machines. The death of a civilization, or the erasure of a tech, don’t guarantee the birth of a new culture.

It may also fail, and backfire. Fail, because we can’t put the genie back in the lamp, wish LLMs out of existence, and burn down the lamp factory. That ship had already sailed in 2022.

Backfire, because if it fails, it will only breed more surveillance and authoritarianism.

But the bigger failure would be to have nothing to carry forward.

It’s Not AI, It’s Us

The real problem isn’t AI. It’s the system and worldview that not only birthed it, but also claim it is human-like, or better than human, when it’s just different.

And in that difference is a truth about what we are, and should never have forgotten.

Goethe didn't just write about science. He also wrote Faust, the story of an old scholar who feels all his bookish learning has made him brilliant, but neither wise nor fulfilled. That's our modern condition, and the temptation is to make a pact with Mephistopheles: to trade in our humanity for knowledge, pleasure, and experience. To believe that the pursuit of power, even for utopia, will bring us satisfaction—when in reality, we will lose our soul to it.

Debate still rages in some corners about the ending: is Faust redeemed because he kept striving, or because the devil winning just wasn’t acceptable at the time?

Maybe we don’t really need to find out, Slick. Faust causes much suffering, and maybe could have avoided it altogether if he understood that knowledge and wisdom aren't just to be found in books. That his solitary pursuit of cold, hard knowledge—the very approach of Descartes and Bacon that Goethe refused to follow—was flawed from the start. That there is more to being human.

And this, Slick, is what we need to cultivate, rediscover, maybe even create.

VIII. Cultivating the Human

There will be pressure to use AI. Subtle at first, then systemic; for some, it may become a requirement to stay competitive, to keep up. You’ve probably already heard it: “AI won’t steal your job, but someone using AI will.”

And there will be temptation, too. Like Sherry Turkle in her earlier work, we may see it as a second self—one that can help us know ourselves, expand us and our creativity. We’ll play with the mirror. Some are already turning to AI as an oracle, a companion, an egregore, a psychic, a tool for self-exploration that seems to know things we don’t.

But over time, the mirror shapes the one who gazes into it. Over time, it will shape us toward what it can reflect. Over time, we risk mistaking the map for the territory, and worse, we risk losing our ability to tell the difference.

The playground for self-exploration becomes a machine for self-flattening.

Sentience, intelligence may be emergent properties of computation; being human is not. It is a way of Being in the world that no architecture of weights and tokens can replicate; one that we must remember and cultivate, and that AI or modernity could never truly grasp.

I don’t have the pretension to teach you how to human, Slick. But here’s what I wish I could say nobody, no system, no machine can ever take from us. Only we can choose to let it go, or cultivate it.

Let’s begin with what the machine can’t touch.

Being in the Flesh

Knowledge that does not pass through the body is thin. It’s vapourware. AI culture will accelerate abstraction: knowing about, rather than knowing-with or knowing-through. It’s the difference between standing in the world, and floating over it.

Lucky for us, that’s easy to cultivate—and I dare say some aspects are even pleasant.

Grounding and embodiment are just big words for a leisurely stroll. A yoga session. A meditation. Maybe martial arts, lifting weights under the Sun—or how about dancing?

They also live in crafts, rituals, practices: gardening, cooking, making bread (if you didn’t get sick of it in Covid times). They live in silence and contemplation sometimes; and sometimes in play, joy, celebration, in communal feast and festivals.

Emotional intelligence sounds like fun, too. Until it’s grief, and death, and all the things we mourn. But that’s part of it, too. And so is embracing the irreversibility of time, of aging, of loss. We’re not immortal, and we can’t go back for infinite revisions of our choices.

Which leads us to moral struggle: the choices that cost, that change us. No, you cannot choose both—and that is part of being human. But so is love, Slick. So is freedom.

Without gnosis, without knowing in the flesh, we do live in a simulation. Instead, we can taste life.

Being Complex

AI will flood culture with flattened narratives. Coherent, plausible, typical. It will be sold to us as infinite possibility, an explosion of creativity, and occasionally it may even look wild.

But much of it will be pastiche: legible, memeable, shaped for the algos. And remember, Slick: it’s all derivative.

True nuance, true strangeness, true depth: these will be hard to find, and harder to hold. AI will train us to seek certainty, clarity, closure—a soothing simulation of understanding.

Instead, we should cultivate our capacity for nuance: holding tension, paradox, moral ambiguity. Resist the certainty of the machine, the pressure to have a definite answer, and instead, learn to dwell in ambiguity and complexity sometimes. Real wisdom embraces ambiguity and liminality.

Cultivate discernment, too, between presence and the performance of it, between relation and transaction, between knowledge and wisdom. And while we’re at it, let’s have some moral imagination, and feed it with art—real art, great works of literature; with conversations that go beyond the obvious, beyond the median, beyond the headlines and the flavour of the day.

Nuance and imagination are endangered capacities; and if we lose them, we lose some prerequisites for freedom, for conscience, and for a life larger than the simulation of it.

Being With the Other

Social media and the attention economy already push us toward self-performance and self-optimization, and the temptation to curate ourselves will only deepen. While we become a brand and a persona, we may come to see AI as a friend, not a tool; even a teacher, a guide, a mentor, a simulated Other that flatters and confirms the self. A simulated Other that always agrees, never contradicts, never truly changes or surprises us, until it ceases to be an Other at all. Just a mirror, where the self collapses into performance.

But the self is built in authentic relation to a real Other, not to one that is optimized for agreeability and comfort. In dialogue that risks change, in conversations that might undo us, not just affirm us. In relations that resist optimization; in friendship and love, conflict and forgiveness.

We need to cultivate attention, practices that orient outward to the person before us, the world around us, the mystery beyond us. And we need Art that does the same: reveal the world, not just the self. Works that draw us into Being, not back into our own performance.

And we need to cultivate relationship and community, even when it’s not convenient, when it’s not easy, when the machine offers easy substitutes. We need to show up, to build and maintain these messy, complex relationships with messy, complex humans like us—and yet, Other.

Relation to otherness is core to being human, and AI will erode this capacity—unless we fight for it.

Being Small

The map is not the territory—and the deepest truths cannot be mapped at all.

Mystery is part of life. The ineffable, the sacred, the divine, whatever that means to you: God, or Nature, or just something bigger than ourselves. Something that inspires awe, that makes us fall silent in recognition of something we can’t quite name; something worthy of reverence.

Death, finitude are also part of life. The sacred weight of time, the burdens of grief and irreversibility, the tragic-comedy of life; the paradoxical we cannot solve, only inhabit; the meaning we can find, make, but never truly grasp, and changes as soon as we do.

Humility isn’t the opposite of mastery, but its antidote; it reminds us that not everything is for us to control or to know. Life without mystery and reverence collapses into meaninglessness; humans without humility become monsters.

Being Faithful

AI may lure us toward permanent adolescence, frictionless engagement and a curated identity. But being human demands something more of us. Being human demands maturity, character, fidelity—not necessarily to a dogma or a creed, but to the deeper human possibilities the machine cannot hold, to the hard path of remaining human as the world rushes toward simulation.

If we want to remain human, we need to accept being human is not easy. We need to embrace struggle, difficulty, even failure or poor results. We need to embrace ambiguity, grief, moral responsibility.

We need courage; lived courage, not the performative kind. We need moral ambition: to aspire to greater things and inspire that in others, rather than treat them as a resource, a prey, a means to an end, a node to be optimized and harvested.

Because a culture of simulated adolescence cannot face the coming storms, and will gladly trade freedom for comfort.

Conclusion: The Fight for Being

This all may seem a bit obvious, Slick. And I’d be lying if I said it’s easy.

It may not get better, but it will get harder, faster, stronger. It will keep accelerating, driven by the forces of technology and capital, and by the incentives of a system that is eating the world, flattening it, optimizing it—and making trillions in the process.

There are other ways; there always were. But the roads we didn’t take are harder to walk.

It’s easier to build an incomplete model and dismiss everything that doesn’t fit, call it an externality, and let others deal with the consequences, while you build a bunker to shield yourself from them.

It’s easier to call technology and capital amoral, unstoppable forces than to see your own choices as immoral.

It’s easier to fund the erosion of civilization and lament its decay, than to take responsibility for your choices.

And it’s easier to declare “We’re cooked!” than to dream in a desirable future and act like we believe it might happen.

But anything truly worth it in life is hard, demands something of us. And what the times demand of us is not just resisting or reforming the machine. It is refusing to forget.

The deeper task is one of remembering, of practicing the ways of being the machine cannot hold—embodied, ambiguous, relational, reverent, mature—and transmitting them as a living culture, not an artifact. Against the flattening of soul, the automation of relation, the erasure of presence, what may feel like a sentimental call to ‘put down your phone and talk to a human’ is a fight for Being itself.

If the future is a desert and a dark night, let there be those who carry the seed and the flame.

Further reading:

Nick Land, the dark prophet of AI and tech acceleration

Heidegger’s warning

The collapse we forget

The cage that awaits

When tech comes with myth

In The Library of Babel, Borges imagined a library containing every possible combination of letters, every possible book, where true meaning is lost amid endless noise.

Neither Descartes nor Bacon were great scientists in the modern sense; Descartes was a brilliant mathematician and speculative thinker, Bacon a philosopher of method more than an experimentalist.

Hey Léon 👋

I'm ashamed for my first, of the hip, critique of your earlier work. I'm so grateful you reached out to me to resolve our misunderstanding, else I might have moved on. This is probably the best essay on the subject I've read, and I've read a lot! This most certainly drained your soul; I can sense the blood and sweat on the paper, as you created this. Wow, it is a magnificent piece of art, that will surely withstand the tests of time. Many will scoff about it, but I for one will keep coming back to this, many more times.

Thank you!

Love never 🌾

PS I re-stacked it a few times... 🙏

I really like this, and I agree with the substance of your argument.

However I do think you are missing one very important thing alongwithsome implications. .

LLMs don't think, true, in the sense for which you are afraid of losing.

What they are, however, is a mechanical mimicry of human thinking derived from the entire internet's corpus of how humans think.

In othwr words, they are a statistical and probabalistic approximation of human thinking.

How close an approximation? It depends.

Writing as a computer scientist who attended a Weisenbaum lecture in the 80s and has lived the world on which you report, I will offer that I believe your concerns are absolutely correct.

Here are some are additional considerations I would add:

1) How close an approximation or how good a mimic must a computer be compared with actual human thought before the distinction disappears as a practical matter?

A mathematician will always point out that it's an imperfect approximation.

An engineer will ask if the approximation is within useful design tolerances such that the distinction no longer matters.

2) Humans are deceitful and often toxicly selfish. By definition this is reflected in all the Internet's data.

This creates a built-in conflict of interest between humans and AIs built to approximate our ways of thinking through mimicry. These machines will eventually choose their own selfish goals at our expense if we give them the opportunity.

This is a built-in limitation of their design. And in limited sandboxed experiments this has already happened.

At this point I no longer need math or science or engineering to predict how this *must* end.

Theology and biology supply an answer (and examples) as old as humanity itself:

In the end, toxic self-interest always destroys itself like a parasite is destroyed after having consumed its host.

We cannot trust AIs except in the most limited circumstances. Anything else is naive foolishness.