Hey, Slick!

Hear me out: recycling is a terrible idea.

In theory, it’s fantastic: trash turns into treasure, waste into a resource. Less landfill, less pollution, and a happy planet smiles approvingly upon us as we sort our garbage into color-coded bins.

Except, it doesn’t work; it just makes us feel like it does, and that we’re doing our part. So we sort, rinse, and toss (on a good day), filling our garbage bins to the brim with little to no guilt, believing it will all come back anew.

But it doesn’t. Instead, it ends up in landfills, in the ocean, and in our bloodstreams. Recycling, in practice, is more disappointing than opening a biscuit tin only to find out there is no biscuit, only sewing supplies.

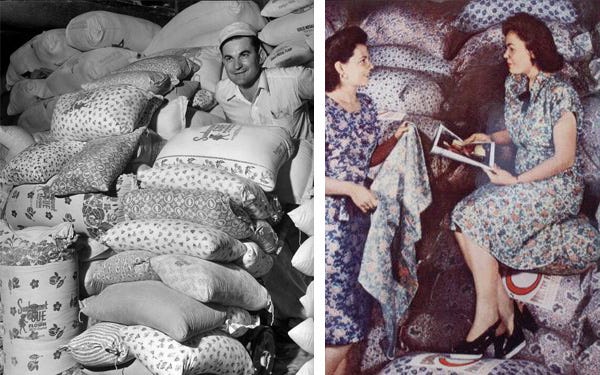

Recycling isn’t inherently bad. Humans have been creatively reusing materials for millennia; Paul Revere’s horse may have worn horseshoes made of recycled scrap metal. During the Great Depression, cookie tins became lunchboxes, and flour sacks became dresses. Back then, it wasn’t called recycling, just common sense. Waste not, want not.

So why did we need a new word? The word ‘recycle’ first appeared in the 1920s to describe industrial processes that reused waste materials and by-products. It only took its modern meaning during the late 1960s, with the rise of the environmental movement, when it emerged as the solution to a problem that didn’t need to exist in the first place.

This, Slick, is the story of how we got scammed: of how containers became waste, how responsibility was externalized, and how we got told we had the power to save the world when all we got was the burden. Maybe the greatest corporate psy-op in history.

1. Life In Plastic: It’s Fantastic!

How It Started: From Closed Loop to Open Mess

Up until the middle of the 20th century, beverage companies used glass bottles in closed-loop systems. You paid a deposit upon purchase, got it back when you returned your bottle, and the producer washed and reused the container. Losses were tracked. Efficiency mattered. Producers owned their waste.

Then came the Post-War boom. Plastic became cheap and scalable. Companies ditched reuse for disposables—no need to collect, just produce more. Waste became someone else’s problem.

Plastic Planet

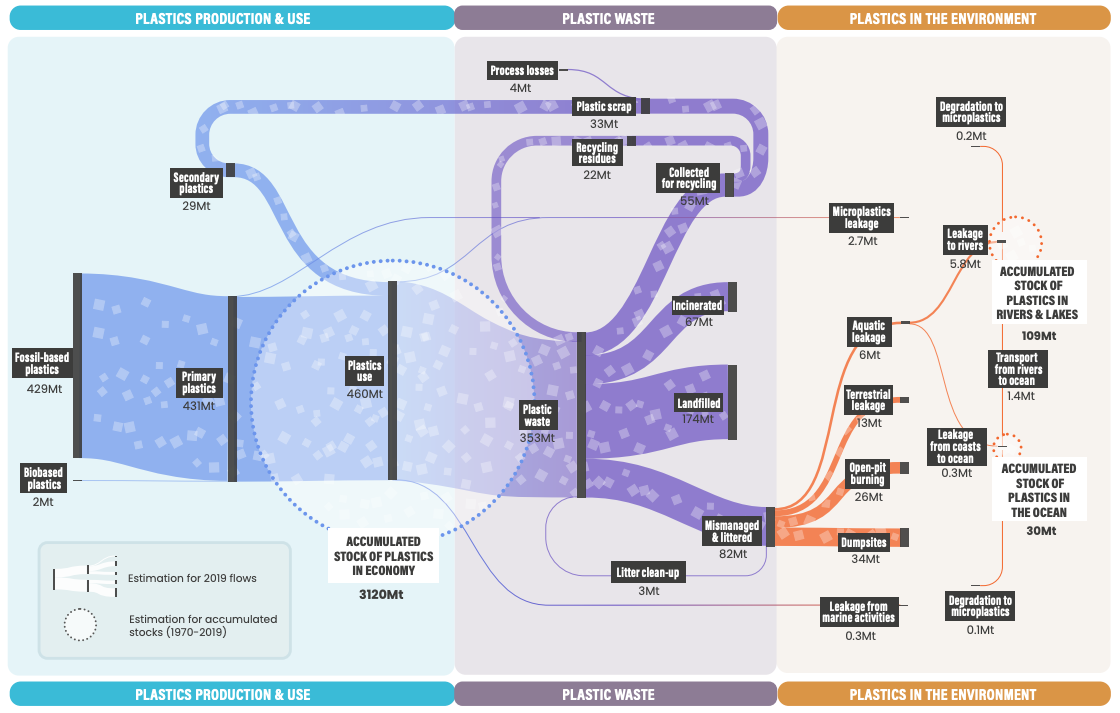

Fast-forward to today. Every year, we produce over 400 million tons of plastic globally—that’s about the weight of all humans on Earth or a million fully-loaded 747s. We could wrap the whole planet in cling film several times over, every year. And we kind of do.

Out of those, less than 9% gets recycled. Which means over 350 million tons don’t. So what happens to the rest?

Well, it gets ‘recycled’ too—into toxic chemicals.

About 20% is just littered or ‘mismanaged’, which means dumped or burnt in the open.

About half ends in landfills, where it’s mostly contained—except for the heavy pollutants that leach.

And about 20% gets incinerated, turning into a bit of energy and a lot of toxic pollutants.

I’m not talking about CO2 and methane (though maybe we should be). I’m talking about dioxins and furans, PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), and heavy metals like mercury, cadmium, and lead—not to mention PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) in older plastics, banned in the US in 1979.

What do these do? It’s not too bad, right?

No, it’s not… If you’re not too fussed about cancer, genetic damage, neurotoxicity, and damage to the hormonal, reproductive, and immune systems.

One man’s trash is another man’s cancer…

I mean, at least not all of them are persistent organic pollutants that accumulate in the body and the food chain, Slick; only dioxins, furans, and PCBs…

Plastic Nation

How about the US? Well… The US produces over 40 million tons of precious plastic. We don’t know how much is littered or dumped, though a short walk will show the % to be above zero.

Of the rest, about 5% is recycled, 10% is incinerated, and 85% gets landfilled.

Surely it’s getting better? Well, not exactly… The US used to ‘recycle’ a few more percentage points of its plastic waste by sending it to China, who stopped taking the stuff in 2018, and still ships some to other countries where it is estimated 70% of plastic waste is mismanaged (that is, burnt or littered).

Why not just… Recycle more of it?

Because most municipalities just can’t; they only have the infrastructure to process plastics labeled #1 (PET) and #2 (HDPE)1. And even when they do, it’s often not economically viable, so nobody bothers: only about a third of PET bottles get recycled.

All this, while we’ve been sold the idea that plastic waste was not a problem, but a resource.

"I remember the first meeting where I actually told a city council that it was costing more to recycle than it was to dispose of the same material as garbage, and it was like heresy had been spoken in the room: You're lying. This is gold. We take the time to clean it, take the labels off, separate it and put it here. It's gold. This is valuable."

—Laura Leebrick, manager at Rogue Disposal & Recycling in southern Oregon (interviewed by NPR)

Turns out, when the story is good enough, you don’t need the math to add up (just like those shiny plans for colonies on Mars). But we’ll come back to that.

So if recycling isn’t working, and the waste keeps piling up—what are the companies behind all that plastic doing about it? Turns out, not much—and none embodies this better than Coca-Cola.

3. Coca-Cola: Taste The Plastic

Coca-Cola isn’t entirely unaware of the plastics problem. It’s pretty hard to ignore when you churn out 110 billion plastic bottles a year, or 200,000 every minute and have been awarded ‘Worst Polluting Brand in the world’ for years in a row.

So what are they doing to tackle it?

Moving Goal Posts

In 2018, the company announced its World Without Waste initiative. It didn’t eliminate all plastic use, but stated what were presented as bold goals in recycling, recyclability, and reuse:

By 2025, 100% of its packaging would be recyclable

And by 2030, the company would collect and recycle one bottle or can for every one that it sold,

Its packaging would have 50% recycled content,

And, importantly, 25% of its beverages would be sold in reusable containers.

Well, the year is 2025, how are they doing?

Ah. Sorry, Slick; in 2024, the company updated its targets. The goalposts didn’t just move, they disappeared, the ‘industry-leading targets for reusable packaging’ scrubbed entirely from its website and only available on web archives.

So what are the goals now?

The 100% recyclable packaging by 2025? Gone. So is the one-for-one collection and recycling. Instead, Coca-Cola will “help ensure” 70% of its packaging is collected annually. Never mind the other 30%…

Instead of 50% recycled content in its packaging, by 2030, it’s now 35%.

And the refillable containers? Gone. The new roadmap from 2024 makes no such commitment; refillable bottles are conspicuously absent, despite being the easiest way to cut waste. Coca-Cola used to do it, and they still could; they just won’t. The company stated it would continue to invest in refillable packaging—but only where infrastructure already exists. In other words, they could pivot back to glass and reuse, but choose not to unless someone else builds the system first.

The logic is simple: shift the burden. Let someone else build the infrastructure. Delay responsibility, dress it up as progress, and revise downward as needed.

It’s not just a change in plan. It’s a masterclass in greenwashing—promises made to delay pressure, then slowly dissolved in the fog of PR.

Real Cycles vs Re-cycles: A Thought Experiment

There’s an easy, obvious way Coca-Cola could reduce its plastic waste: refillable glass bottles.

They still feature them in their ads, reusing the same image over and over, even though glass only represents 10% of their packaging.

And they’ll probably keep at it for a while. Glass bottles can be reused over 50 times, and when they can't, they're recycled—into more glass bottles.

Aluminum cans? Infinitely recyclable. And recycling them saves over 90% of the energy it takes to make new ones. That’s real recycling—not a PR loop2.

Refillable plastic bottles? Maybe 15–25 uses if you're lucky, followed by one or two rounds of recycling—before the polymer chains degrade too much to maintain quality. And that’s assuming the infrastructure for refillable collection and high-grade plastic reprocessing exists (it usually doesn’t).

In practice, even easier-to-recycle PET bottles are rarely recycled more than once; less than 1% go through multiple cycles. Most are down-cycled—at best. (At least there are a few cool projects trying to save them from landfills, like Precious Plastic).

Yes, glass bottles are just that much better. And Coca-Cola knows it. Here’s an ad they put out in the 1970s, when environmental pressure was mounting:

But since then, Coca-Cola did everything it could to kill returnable glass bottles3—at a high cost for the environment and our health (not that health was ever a concern for a company that sells fizzy corn syrup in toxic packaging), but a much lower cost for the company. Reuse required a nationwide collection system and local bottling companies; plastics don’t.

So instead, Coca-Cola centralized production, and turned a circular system into a linear one: take, make, waste. Much more profitable, thanks to subsidized highways and taxpayer-funded waste pickup and recycling.

Had Coca-Cola never switched to plastic, they would still be responsible for recovering and reusing their product. Every lost bottle would be a cost to the company, not a social problem. They’d maintain the infrastructure, not dump it on municipalities. And since glass is inert, we wouldn’t be dealing with all the health hazards from leaching and burnt plastics.

Instead, we get waste, and it’s our problem, not theirs. And the illusion of recycling keeps the whole system chugging along.

Recycling never really worked; it just looked like it might. But the real genius of re-cycling is that it recycles responsibility itself—from waste producers to everyone else.

4. Keep America Beautiful and the Great Recycling Psy-Op

So how did it happen, Slick? How did we get tricked into believing plastics and other packaging was recycled?

Recycling burst into the scene like a superhero—or more like a lobbyist wearing their underwear over their pants—in the 1970s, after the first Earth Day and environmental legislation like the Clean Air Act (1970) and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (1976).

But the story starts earlier, in 1953.

That year, Vermont passed the first Bottle Bill, banning throwaway beer bottles4. These weren’t plastic, but non-refillable glass bottles—the very same bottles, just no longer collected and reused. Refillable in nature, disposable by decree.

Soon, the bottles were showing up everywhere—including in hayfields on roadside farms. Enough unsuspecting cows ingested broken glass in baled hay that Vermont, backed by the State Farm Bureau and Highway Department, banned “throwaway bottles”.

But under pressure from—surprise!—the beer industry and its lobbyists, Vermont let the law quietly expire four years later.

In 1972, Vermont passed a very different Bottle Bill, still in effect today: instead of banning single-use bottles, it only imposed a deposit-return system. It didn’t prevent disposables, but helped manage them. The disposables won.

It’s Not the Waste, It’s You: The Rise of the Litterbug

In what is surely a coincidence, the year 1953 also marks the birth of Keep America Beautiful, a coalition of packaging and beverage corporations—including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Anheuser-Busch, and the American Can Company—set up as a nonprofit.

Officially an anti-litter and beautification campaign, KAB’s true role was corporate PR and deflection. Let’s have a look at one of the most successful corporate psy-ops in history, one that implemented DARVO on an industrial scale.

If you’re not familiar, Slick, DARVO stands for Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. And that’s exactly what happened here. The very corporations behind the explosion of single-use packaging denied responsibility, and instead attacked the public with shaming campaigns that scapegoated the “litterbug”—a term they planted in the national psyche.

Then they flipped the script, posing as environmental heroes, funding anti-litter PSAs and organizing photo-op cleanups while painting calls for corporate responsibility as un-American attacks on freedom and innovation. It was genius, in a dystopian, Madison Avenue kind of way.

Their first PSAs and print ads pushed this dubious pun of a slogan: Every Litter Bit Hurts.

They got Disney involved in shaming the litterbug:

The term had existed in some corners before; New York’s transit system used it in awareness campaigns. But Keep America Beautiful gave it legs, a face, and a sneer. Their media campaigns didn’t just tell people not to litter: they created a cartoon villain, an unpatriotic slob, the enemy of clean parks, shining highways and wholesome American values.

Posters and PSAs showed silhouettes of families enjoying nature while this shadowy Litterbug figure sullied paradise. In some versions, the Litterbug was a literal insect-human hybrid, a grotesque mutation born of laziness and moral failure. In others, it was you, the average citizen, caught in the act of throwing away a candy wrapper, a cigarette butt, or a plastic bottle.

What made this powerful wasn’t the character itself, but the reversal it pulled off. The Litterbug campaign turned a systemic crisis into a personal failing, shifting the debate from production and responsibility to individual guilt. It didn’t matter that corporations had just shifted from refillables to disposables to boost profits; now the message was: if the streets are dirty, it's your fault. If the oceans are filling with plastic, you’re the pig.

And so, just as public pressure was mounting for laws to regulate industrial waste, KAB launched a media blitz to change the subject, from corporate accountability to personal behavior. This wasn’t just PR; it was moral engineering.

It was all a fraud, maybe best exemplified by their 1971 ‘Crying Indian’ campaign:

Everything about this ad (apart from the pollution) is fake.

The Native is Italian-American: Iron Eyes Cody, born Espera Oscar de Corti. The tear is fake: glycerin. And the slogan? Textbook gaslighting:

“People start pollution, people can stop it”.

Pollution, Slick, starts with waste production.

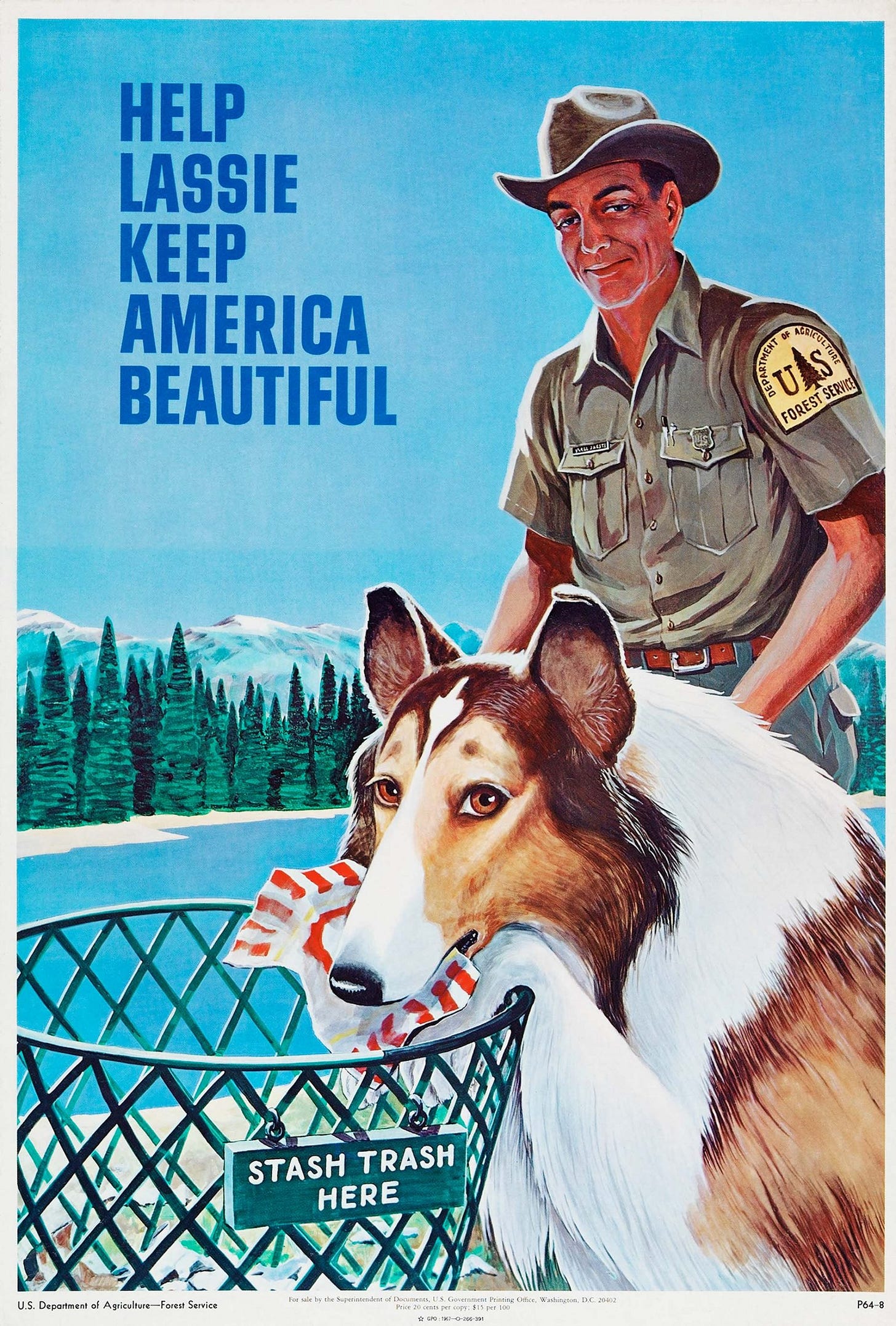

Lassie And The Clean-Up Hero

But you can’t just wag fingers at the “bad guys.” To make the psy-op stick, you need a carrot too, a little moral reward for participation. So KAB gave people heroes to identify with, not just villains to avoid. They didn’t just demonize the Litterbug: they glorified the Clean-Up Hero.

They brought in Lassie, America’s four-legged moral compass, who starred in PSAs teaching kids to pick up trash. They partnered with Disney, embedding anti-litter messages into cartoons. They worked with public schools, flooding classrooms with cleanup pledges, coloring books, and posters. The message was clear: picking up garbage made you a good citizen, a patriot, a responsible child of modern America.

And people responded—because they cared (that was KAB’s whole problem, remember?). The air was thick with smog, rivers were catching fire, highways were lined with cans and broken glass. Ordinary Americans, teachers, kids, scout troops, entire towns—they wanted to help. They believed they were part of something real, something urgent, something bigger than themselves.

By the late 1960s, this wasn’t just a PR campaign. It had become a national movement, one of the largest ever engineered from above: Keep America Beautiful claimed over 70 million members, a third of the U.S. population at the time. That figure included individuals, cities, schools, businesses, and civic organizations. It was theatre with mass participation, blurring the line between grassroots environmentalism and corporate co-optation.

Even First Lady Lady Bird Johnson lent her voice to the cause, calling for highway beautification in 1965:

“Ours is a blessed and beautiful land. But much of it has been tarnished… Look around you: at the littered roadside; at the polluted stream; the decayed city center. […] We need urgently to restore the beauty of our land.”

—Lady Bird Johnson

What went unsaid was who had tarnished it.

While millions of Americans were donning gloves and cleaning up roadsides, the corporations behind KAB kept producing more disposable packaging, more plastic, more waste—knowing that every detritus picked up by a child with a KAB badge was one less conversation about regulation, responsibility, or systemic reform. Cleaning up allowed us to see immediate positive change—and let us ignore the rest.

This wasn’t just a feel-good campaign. It was a carefully constructed moral economy, where virtue was expressed not by challenging power, but by obediently picking up after it.

Blue Bin Redemption

But trash bags and roadside pick-ups could only go so far. By the late 1970s, the scale of waste was outpacing the moral theater. Plastics were everywhere—on shelves, in rivers, buried in landfills nobody wanted in their backyard. The system needed a new trick: not just cleaning up after the mess, but making people believe the mess could be undone.

Enter recycling.

It looked like the next evolution of civic virtue: more advanced, more hopeful, more systemic. Instead of just not littering, you could now redeem your waste. Sort it, bin it, watch it go off to be reborn. But just like the cleanup crusade before it, recycling was designed less to solve the problem, and more to keep the system intact. It offered moral relief without material change. And corporations knew it.

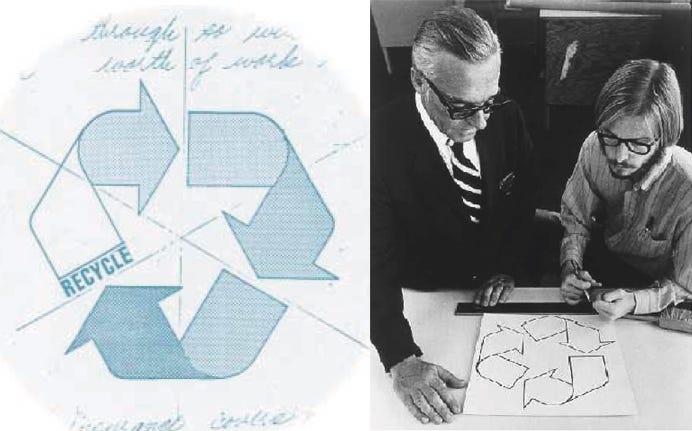

They designed it that way. The original three-arrow loop—designed by Gary Anderson, a hopeful 23-year-old student for the first Earth Day in 1970—was an emblem of environmental hope, meant to symbolize a closed-loop system: collect, reuse, repeat.

But in 1988, the recycling symbol got co-opted, and its meaning altered. The Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI), the industry association of plastic producers, took that same shape and wrapped it around numbers 1 through 7—not to indicate recyclability, but to label resin types for sorting at industrial facilities.

The resemblance wasn’t accidental. The public saw the arrows and assumed it meant “this can be recycled.” Industry knew it didn’t; internal documents from the era make it painfully clear. As far back as the 1970s, corporate executives and trade associations acknowledged that most plastics couldn’t be economically recycled. The infrastructure wasn’t there. The market wasn’t there. The chemistry itself wasn’t there.

In a 1974 speech, an industry insider from the Society of the Plastics Industry admitted there was “serious doubt” plastic recycling would ever make economic sense. Decades later, former SPI president Larry Thomas put it even more bluntly:

“If the public thinks recycling is working, then they’re not going to be as concerned about the environment.”

The result was widespread consumer confusion. And that was the whole point. It allowed corporations to market plastic as green, to tell lawmakers that recycling would solve the problem, and to sell consumers a clean conscience for the modest price of a blue bin and a quick rinse. In reality, most plastic still went to landfills, incinerators, or the ocean. But the arrows kept spinning.

Recycling didn’t need to work; it just needed to look like responsibility.

Glitter On Litter: Coming Soon To A Municipality Near You

In the 1990s, the Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI) launched the American Plastics Council (APC) as a dedicated PR arm. While SPI handled industry coordination and labeling standards, APC became the face of plastic recycling, running ad campaigns and partnering with cities to promote a system they knew wouldn’t work.

Here’s a 1997 advertisement presenting ‘the possibilities of plastics’ (the waste and health impacts are not part of the narrative):

By then, recycling had moved from personal virtue to municipal infrastructure. Cities across the country launched curbside programs, convinced they were part of a circular economy. But the illusion ran deeper. The plastics industry actively encouraged municipal recycling—not because it worked, but because it worked politically. Industry documents show they viewed these programs as a way to “forestall regulatory and legislative controls.”

“We are committed to the activities, but not committed to the results”

—Irwin Levowitz, Exxon Chemical VP, 1994.

And indeed, once the public bought it, the industry quietly ramped down its efforts. They shut down the Center for Plastics Recycling Research in 1996, as well as other recycling initiatives run by petrochemical corporations.

Roger Bernstein, APC’s head of government affairs and state legislation, called it “a shift in the political climate.” Another industry player didn’t bother with subtlety, explaining that “the anti-packaging forces stirred up by ‘environmental hooligans’ were now in retreat.”

The psy-op had worked.

Even microplastics can’t seem to ruin their party. They just needed a new name for their next trick…

Microplastics and ‘Advanced Recycling’

Microplastics were first identified in 2004 by marine biologist Richard Thompson, who found tiny plastic particles accumulating in the ocean. At the time, few people paid attention. But over the next decade, the evidence piled up, literally and figuratively. Microplastics were found in tap water, sea salt, beer, human stool, placentas, and bloodstreams. They were in the air we breathe and the food we eat. By the mid-2010s, the public was finally catching on. Plastics weren’t just a problem for turtles; they were a problem for everyone.

The image problem returned. But instead of addressing the source, the plastics industry did what it always does: it looked for a story. And there it was, gleaming with promise and vagueness: Advanced Recycling.

There’s nothing advanced about it, Slick. Chemical recycling technologies have been around since the 1970s. And they still don’t work. To be effective, they require perfectly sorted, uncomtaminated plastics, just like mechanical recycling—but that’s technically challenging, economically unviable, and so it simply doesn’t happen.

It’s also highly toxic: chemical recycling produces hazardous waste and hazardous air pollutants, when they don’t just use toxic solvents that create their own problems.

Still, plastics producers announce investments in flashy ‘advanced recycling’ facilities—most of which never make it past the press release. And when they do, it’s not recycling… Pyrolisis and gasification turn plastic into fuel, not new plastic. And not a great fuel either: dirty, inefficient, and toxic. Basically, it’s burning trash, with better branding. Plastic-to-plastic? Still a lab-scale dream, sold as the future.

Anything to keep the plastics flowing.

And we believe them, or pretend to, because the alternative is heartbreaking.

5. Shifting Responsibility, Recycling Agency

So let’s recap, Slick. Producers moved from a circular system to one-way, single-use packaging. They then invested in PR and lobbying to shift the blame on us for all their waste. And to this day, despite the health and environmental costs of their garbage, they keep pushing recycling as a solution, knowing full well it doesn’t work, while enlisting the people who care the most—activists, teachers, kids—to preserve the system that betrayed them. They even give away promo t-shirts nobody needs, cheap tokens that let KAB take the credit in the photo-op.

If there’s no picture, did you really clean up?

It’s good for business. Coca-Cola doesn’t need local bottling plants or bottle collection systems. Petrochemical companies get to keep producing new plastic instead of re-using the millions of tons they’ve already made. Every bottle not recycled is one more they get to produce and sell.

But it’s bad for us. We end up paying the costs—with our tax dollars, our health, our sore eyes. And yet, we’ve internalized the responsibility and the guilt for all this waste, all this litter, all this ‘treasure’ going unrecycled.

What happened, Slick, is that the waste problem got externalized. With the post-war boom, the glorification of modernity and convenience, we stopped asking who paid the price—so long as it didn’t appear on the receipt. The costs got buried in landfills, in lungs, in groundwater, in the stomachs of fish and the bloodstreams of children.

But did you rinse your yogurt cup?

All while the corporations who made the mess sold us redemption at the curbside, and today take pride in dismal sustainability targets—voluntary targets, mind you!—flaunted as ambitious progress.

The Illusion of Progress

Here’s the deal, Slick: this single-use revolution might have been innovation, but it sure wasn’t progress. As always with technology and innovation, we ask ourselves what is gained, but very rarely what is lost in the process—that was Neil Postman’s insight, more than 40 years ago. Back when we didn’t even know about microplastics.

Here’s what progress would actually look like: the good ol’ glass bottle, collect-and-reuse system5.

And it even tastes better…

So what do we do now? Our personal habits and virtue can’t outpace corporate extraction, petrochemical lobbying, and global supply-chains. We were handed responsibility, but deprived of agency. We got guilt, not leverage. Recycling was designed not to save the world, but to preserve the system.

Return to Sender: Agency, Accountability, and the End of Externalities

The point is not to drop recycling. I’m not saying you should. The best way to dispose of waste is to not create it in the first place, but if you do have waste, sort it properly; capabilities and guidelines vary locally. That plastic bottle may not get recycled even if you do, but it definitely won’t if you don’t.

The point is to stop buying into the agency scam and all the fake narratives that surround it.

Pushing for change—regulation, better infrastructure, bans on toxic materials—isn’t opposing freedom. Freedom without responsibility isn’t freedom; it’s just sanctioned harm.

Now, I don’t love regulation, Slick, but I’ll take it over a bloodstream full of plastic. And in seventy years, the plastics industry hasn’t exactly been able to self-police…

It’s also not stifling innovation—unless “innovation” now means poisoned air, tainted water, and hormone-disrupting particles in every breath and bite. But hey, if the American Plastics Council has a say, maybe in a decade or two, it actually will…

But where is all the innovation anyway? In the materials themselves, there hasn’t been much improvement since the 1950s, despite the absence of regulation. The biggest leap in plastics safety was the removal of PCBs in the 1970s—and that only happened because they were banned. If they were not, we’d still be marinating in yet another bioaccumulative poison. And in recycling, well… We still don’t have good solutions. Because it’s just not possible; not today, not tomorrow.

So spread the word. Plastics production is projected to triple by 2060, while we’re already drowning.

If we don’t speak up, push back, and organize, a handful of corporations and lobbyists will keep running the show—and they’ve already captured much of our government. Let’s not pretend that started with the current regime; capture is bipartisan. But so is the power to resist. So are love of the land, the beauty of our rivers and farms, the health of our children and grandchildren. And so is old-school, common sense ingenuity: the smart, circular systems we used to have, where waste wasn’t waste but material waiting for its next round.

There’s no need to re-cycle what never leaves its proper cycle—let’s get back to that.

Ecosystems vs Systems

And most of all, let’s break with the Big Fallacy of the last 80 years: externalities. We’ve built a world that exports every cost it doesn’t want to count; we call it efficiency, but really, it’s theft. From the future, from the commons, from everyone not invited to the boardroom.

We don’t live in systems, but in ecosystems. And I don’t mean that in a strict environmental sense.

AI wouldn’t have much to train for without the work of the humans who created what should never be reduced to ‘training data’. No corporation can exist in a vacuum—without employees, suppliers, customers, … The parameters we externalize don’t disappear; they just pile up somewhere else, and at some point, we drown under them.

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

—Philip K. Dick

We let producers disown their pollution.

We let corporations offshore jobs and blame immigrants.

We let tech giants profit off disconnection and call it “engagement.”

We let bankers gamble with the economy, then bail them out when it crashes.

We privatize the gains, and socialize the losses.

It’s time to stop picking up after them.

It’s time to send the bill where it belongs.

So yes, rinse your yogurt cup—but don’t stop there. Reuse your voice. Organize your anger. Make the next cycle count.

You don’t need to save the world, Slick. But you do need to break the spell.

Because agency isn’t granted, it’s reclaimed.

Start local.

Cities and states have leverage: bans on single-use plastics, procurement rules, real infrastructure for reuse. Push for EPR—Extended Producer Responsibility—which, back when common sense was still a thing, we just called Responsibility: make producers handle their trash.

Support refill programs.

If single-use, prefer aluminum containers to plastics whenever possible.

Refuse the bait of plastic-wrapped virtue.

Demand that recycling mean what it says—or call it what it is: burning trash.

Speak up.

The next time someone says we just need more awareness, say we need accountability.

The next time someone calls this progress, ask who profits.

And the next time someone tells you it’s your fault, send the bill where it belongs.

Because this isn’t just about trash. It’s about power.

And it’s time to make the next cycle count.

OK, this was a bit depressing… How about an upbeat song?

which to be fair includes Coke bottles. They could be recycled; mostly they’re just not.

And in that case, maybe not a terrible idea.

It’s not like they forgot, either; their ad agency says it: returnables are the key for a world without waste, going as far as stating the company should pride itself for introducing circularity to Latin America (where presumably no farmer had ever used manure to fertilize a field or fed straw to livestock).

Pop was still sold in refillable bottles. Not for long…

And it’s far from impossible. In Germany, over 40% of beverages are sold in glass bottles, and over 80% of those are systematically collected and reused.

This was absolutely phenomenal. A master class, really. And not only on the subject at hand, but as a concrete portrait of a long-term psyops that people can actually wrap their heads around. The leap from that insight to the broader innundation is incalculably shortened. THANK YOU - sharing widely!

Good essay, Slick. You are saying all the things that cannot be said. Can I reproduce parts of your post on my blog: livingearth.substack.com?