Plato’s Gotcha Moment: a Tale of Two Floods

Atlantis, Athens: On Collapse, Memory, and the Sacred in the Age of Acceleration

“You Greeks are always children”, the priest said to Solon. “You have no old traditions, no ancient memory. You remember one flood, but there have been many.”

These were not idle words. Plato recorded them in Timaeus—not just to preserve a story, but to sound an alarm.

Plato is remembered as the father of Western philosophy. But he was also something else: a prophet.

He didn’t just argue—he remembered. He encoded memory into allegory, shaped myth into mirrors, carved riddles into stone. He wasn’t warning us about the future—he was warning the Greeks about the past.

Plato didn’t write for us—living in an age of acceleration, collapse, machines, and the death of God—but for the Greeks who, like us, believed they were the beginning of everything. Their world and their time was never unprecedented; they had just forgotten how many worlds had ended before.

And so have we.

We're not the only ones who forgot; not even the first. Before us, the Greeks forgot—and Plato was there to remember.

The priest's warning, carried through Plato, wasn’t just about ancient times.

It was a warning to the Greeks—who thought they were the first.

And through them, a warning to us—who think we’ll be the last.

You’ve forgotten the floods. And one of them—the one you don’t remember—was Atlantis.

I’m not here to tell you I’ve found Atlantis, Slick, or that I’ve joined a long line of people looking for it under every utopia, rock formation, and Google Earth anomaly. I’m here to say something simpler, and maybe more unsettling: we’re living in Atlantis.

Which, maybe, was Plato’s point all along.

Atlantis isn’t a place—it’s a pattern.

A shape civilizations take when they gain brilliance—and lose memory.

A mirror held up to any society that forgets its roots, its gods, its limits.

The Greeks were already becoming it.

And we’ve finished the job.

I. The Priest’s Warning: The Children of Collapse

But to understand this, we need to go back.

The story begins not with Atlantis, but with a forgotten conversation between civilizations.

Solon, the great Athenian lawgiver and poet, travels to Egypt—a land old enough to remember what others have lost. In the temple of Neith at Sais, he meets a priest who carries the weight of deep time.

Solon comes seeking wisdom. And wisdom he receives, in the form of a rebuke, once he’s done boasting of Athenian accomplishments in science, philosophy, politics, and overall greatness:

"You Greeks are always children," the priest tells him.

"You have no old traditions, no ancient memory. You remember one flood—but there have been many."

It’s a humbling moment. Athens, proud of its reason and refinement, is told it knows very little of what came before. The priest speaks of vast cycles—civilizations rising, flourishing, and falling—most of them now erased. Some by water. Some by fire. Some by their own forgetting.

Then he tells a story that Solon—and later Plato—will never forget.

"There was once an island," the priest says, "larger than Libya and Asia combined. It lay beyond the Pillars of Heracles, and its empire stretched deep into the Mediterranean. Its kings ruled with great power. Its cities were adorned with gold, its temples vast, its people mighty."

"But they grew proud. They sought to conquer all within reach. And so, in a single day and night of misfortune, the island sank beneath the sea."

Atlantis.

But that’s only half the story.

The priest also speaks of the Athenians—not the Greeks of Solon’s time, but an earlier people, long forgotten. In this tale, Athens is not an empire but a paragon—modest, principled, brave enough to stand against Atlantis and repel its aggression.

And yet, they too are lost.

The flood comes. The earth shifts. The sea rises. And both civilizations—corrupt and noble alike—are swept away.

One for its hubris. The other… we don’t know. It’s a strange justice—no villains, no victors; no rescue, no survivors. Just the flood and what it left behind.

Only the memory survives, and even that, just barely. Not in Athens, not in Greece, but in Egypt—written in priestly scrolls and preserved through ritual remembrance.

Plato, through Solon, preserves it again.

But it’s more than a story. It’s a message.

Civilizations fall. Not because they fail to grow strong, but because they forget what strength is for. Atlantis is not just a lost city. It is the shape of forgetting.

And the priest wasn’t just warning Solon. He was speaking across time—to us.

II. Forgetting: The Flood and the Rock

Forgetting has layers.

The Greeks remembered one flood—the flood of Deucalion and Pyrrha. They didn’t remember the others. And they didn’t remember the flood beneath them—the one they were already becoming.

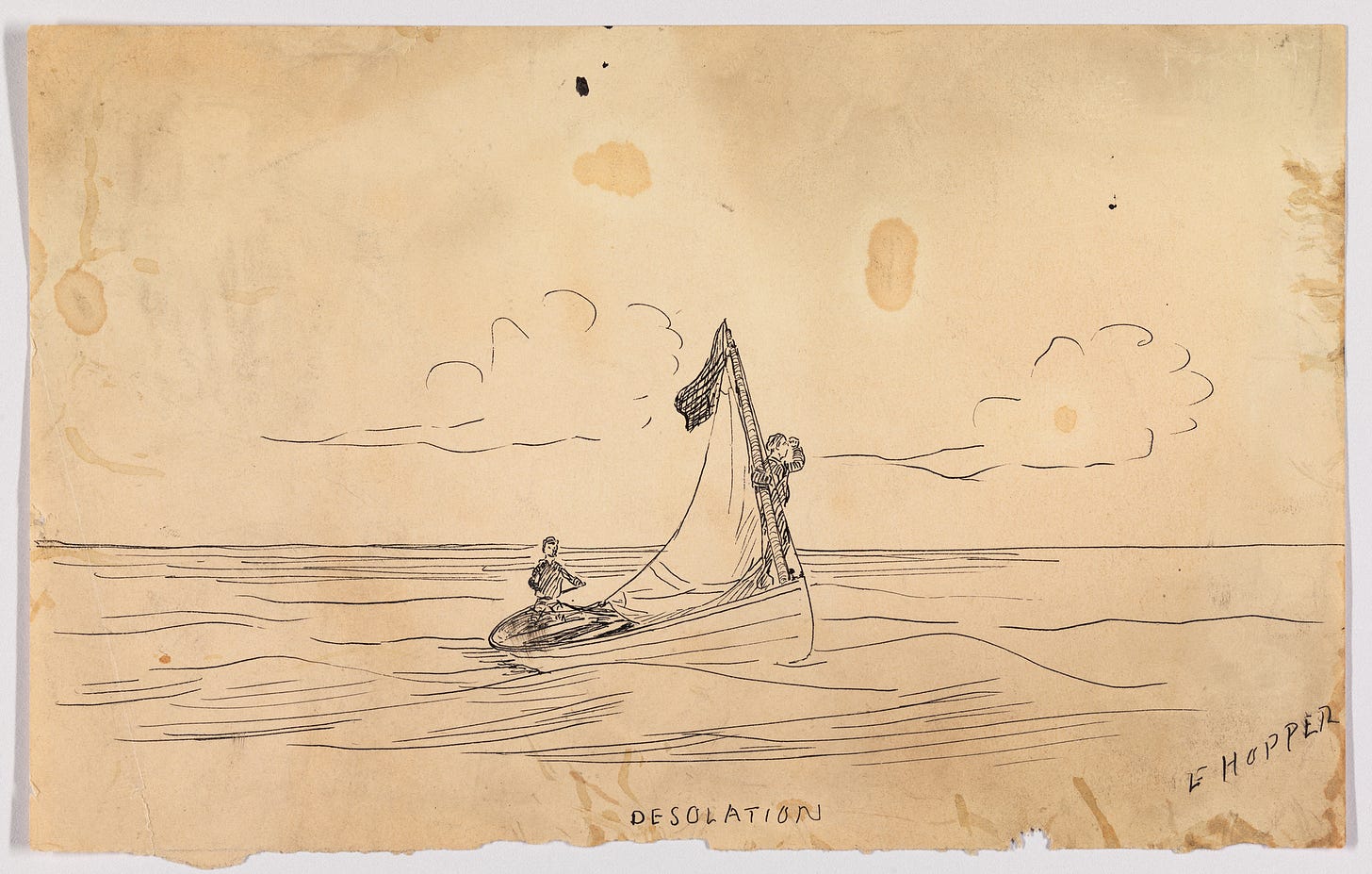

Zeus, angered by an age of arrogance and impiety, sent a great deluge to wipe the world clean. Only a man and a woman survived: Deucalion, son of Prometheus, and Pyrrha, daughter of Pandora. Warned in advance, they built a simple floating chest and drifted in it across the drowned world.

When the waters receded, they found themselves alone, in the silence of a remade earth. No voices. No children. No gods. They climbed to the temple of Themis and begged for a way to restore humanity. The oracle spoke in a riddle: “Cast the bones of your mother behind you.” They puzzled it out—Mother Earth. Stones. So they gathered rocks and threw them over their shoulders. The stones Deucalion cast became men; the ones Pyrrha cast became women.

From stone, humanity was born again.

It’s a story of renewal after judgment, of divine reordering, and of the world made clean. A fresh start, and also an existential break—because after that flood, something changes.

In the time before, the gods walked the earth. They took mortal lovers, fathered children, shaped cities. They were close, tangible, present.

But after the flood, they recede. They stop intervening. They stop appearing.

The world continues—but more alone. Just as in Genesis, when God sends a rainbow and withdraws from the intimacy of Eden, here too there is a quiet covenant: the flood is over, but so is the age of presence. The gods no longer walk the fields. Their voices grow still. Their faces vanish from the mountaintops.

Something has been severed.

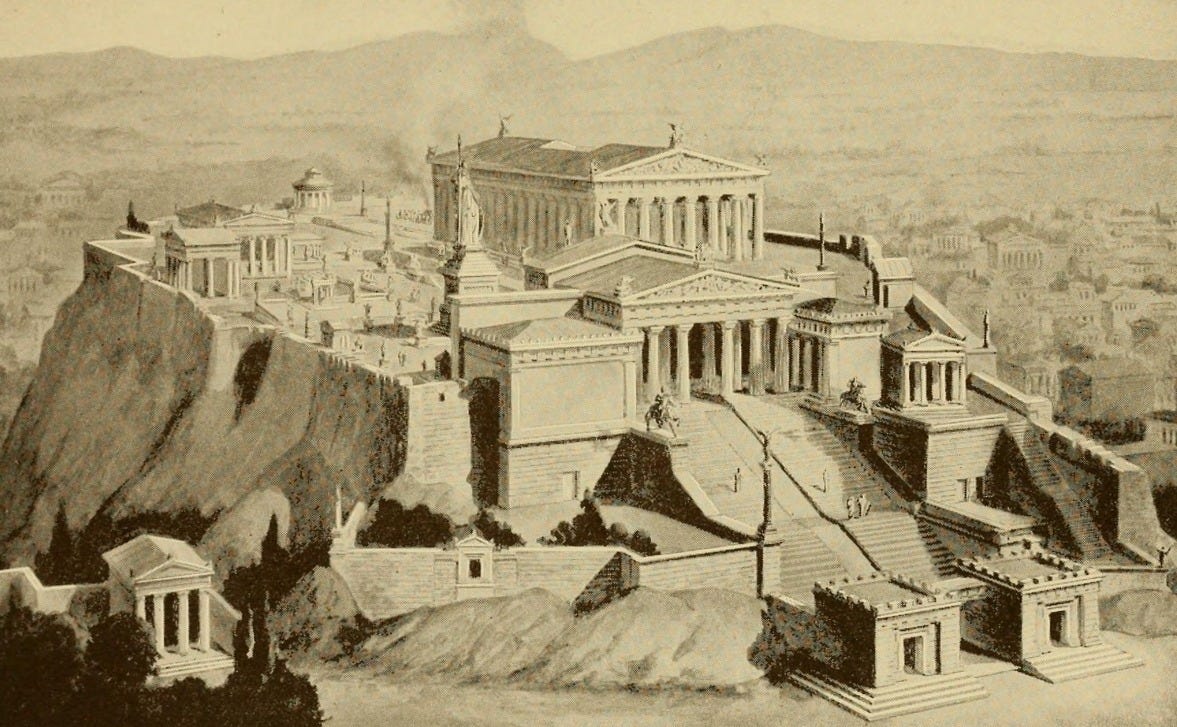

The land reflects this rupture. Before the flood, the slopes around the Acropolis were rich with soil, the hills clothed in green, the rivers threading through the city like lifelines. Athens was not just a city of stone—it was alive. The gods were not metaphors; they were neighbors. People lived in rhythm with the world. The divine was not an abstraction, but a presence woven into the land, the sky, the harvest, the hearth. It was paradise.

But the deluge came. The forests vanished, the rivers dried, the fertile layer was stripped away. Paradise was lost.

What was left? Just a high rock, the Acropolis—towering, exposed, inhospitable.

The city moved down. The gods, up.

Humans could no longer dwell in the sacred heights. And the gods no longer descended to the valleys. A gap opened, a vertical fracture in the world’s intimacy. And in that fracture, meaning began to thin.

The temples remained—but now they were monuments.

The rituals continued—but now they were habit.

The stories were still told—but they no longer rooted.

Athens endured, but only as an echo.

And over time, we stopped climbing the stairs.

Not just literally, but spiritually.

We stopped returning to the heights—not because they vanished, but because we forgot why they mattered.

We built our lives at ground level.

And the temples of the gods became scenic overlooks, tourist spots, museum relics.

This is what it means to forget.

Not to misplace information—but to sever relationship.

And that forgetting is not just ancient.

It’s also now.

We’ve mapped the heavens, but we no longer feel their pull.

We’ve recorded our myths, but we no longer let them remake us.

We speak of progress, but cannot name our purpose.

Plato was not nostalgic for the past. He was warning us that without memory, even the present is unstable.

The rock still stands.

But the garden is gone.

And memory—if it survives at all—must be carried like a seed.

III. Plato’s Atlantis

Atlantis was born of a god. Poseidon, lord of the sea, claimed a mortal woman named Cleito. To protect her, he encircled the hill where she lived with rings of land and water—concentric circles, perfect and strange. There, he fathered ten sons, and divided the island among them. The eldest, Atlas, gave the realm its name (not Atlas the Titan, Slick—not the one holding the heavens on his shoulders. But Plato picked the same name for a reason.)

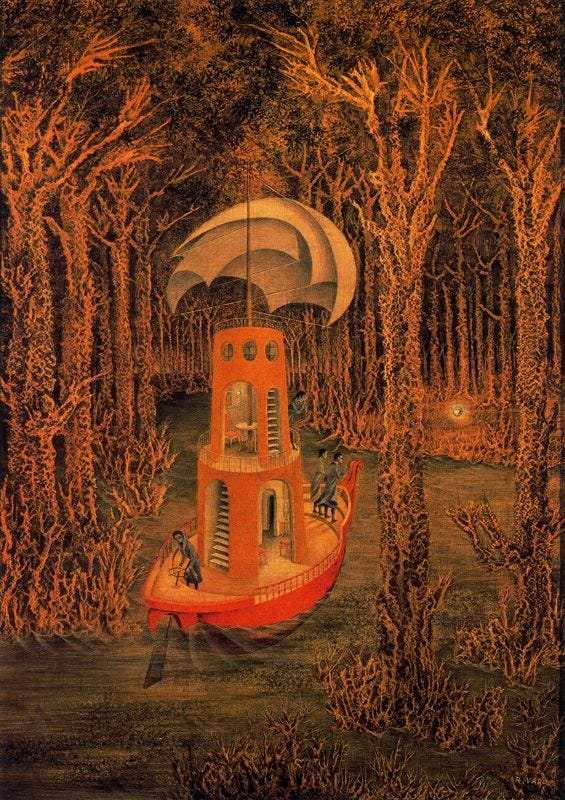

At first, they lived in harmony with the divine order.

The Atlanteans were mighty—but measured. They honored the gods. They governed wisely. Their palaces were adorned, their ports brimming, their people prosperous and just.

The island overflowed with riches: fertile soil, warm and cold springs, abundant wildlife, precious metals. Even orichalcum—a metal second only to gold—was mined from the earth and gleamed in their temples. They built walls of polished stone, canals that shimmered like veins, and temples worthy of gods. They mastered engineering, metallurgy, and navigation. They built not just a city, but a symbol.

And then—they forgot.

The divine portion in them began to fade.

Their mortal nature asserted itself.

They grew proud. Greedy. Restless.

No longer content to tend their island paradise, they turned outward.

They raised armies and fleets and sought to dominate all of Europe and Asia. They reached into the Mediterranean, threatening Egypt—and Athens.

But in Plato’s telling, Athens stood firm. Not as an empire, but as a mirror of virtue: modest, courageous, self-sufficient. Without allies, without wealth, the Athenians pushed Atlantis back.

It should have been a turning point.

Instead—it was an ending.

For reasons never fully explained—perhaps divine judgment, perhaps natural cataclysm—the gods brought ruin. In a single day and night of misfortune, the earth trembled. The seas roared. The island was swallowed whole.

Atlantis vanished.

And ancient Athens vanished too.

The war was erased. The victory forgotten.

Not even the names survived.

Only Egypt remembered.

Only Plato wrote it down.

The story ends not with a lesson, but a silence. No survivors. No covenant. Just a trace in the sand, barely carried forward.

But for Plato, that was the lesson.

Atlantis didn’t fall because it was wicked.

It fell because it forgot.

Forgot its origin, forgot the sacred, forgot that power without orientation is not greatness—but the seed of collapse.

It drowned not just in water—but in meaninglessness.

Plato gives us Atlantis as a myth of collapse.

But the priest gives us something subtler: a myth of forgetting.

The Atlanteans forgot their divine roots.

The Greeks forgot the pattern of collapse.

And we—we forget both.

So yes, we are the Greeks: brilliant, confident, but cut off from memory.

And yes, we are the Atlanteans: powerful, glittering, drifting beyond our limits.

That’s why the myth still burns.

Because it isn’t behind us, Slick. It’s inside us.

IV. The Mirror of Modernity

Atlantis isn’t ancient history.

It’s a warning that never stopped being relevant.

It didn’t fall because it was evil.

It fell because it forgot.

It forgot its origin, its sacredness, its limits.

It became brilliant, ambitious, powerful—and unmoored.

In that sense, it became modern.

And so have we.

Look around, Slick.

We build in rings—concentric circles of highways, zoning districts, surveillance grids.

Our cities are temples of steel and glass.

Our towers reflect the sun like orichalcum.

Our homes are warmed and cooled by invisible forces.

Our ports brim not only with ships but with containers, fiber optics, and silent code.

We drink from fountains we did not build.

We reap from soil we do not touch.

We live in miracles—yet feel no mystery.

We are proud.

We are clever.

And nowhere near wise.

We speak of expansion, efficiency, scalability—as though these are virtues.

We mistake acceleration for evolution; we call our disconnection ‘freedom’ and our forgetting ‘progress’.

But this forgetting is not passive. It is systemic; it is industrialized. We have built an entire civilization designed to forget.

Plato isn’t the only one to warn us. Even in the modern age, the witnesses return.

Neil Postman told us: every technology is a Faustian bargain. It gives something, but it also takes. And what it takes is not just function—it is form, relationship, context. We do not just replace the old—we delete its memory.

Ivan Illich told us: we think we are becoming more autonomous, more powerful.

But we are being replaced—by systems that no longer need us whole. Herbert Marcuse told us too: When all things become tools, we become the tools of our own tools.

We live in Atlantis—but without even a memory of the gods.

The sacred is absent not because it was disproven, but because it became irrelevant.

We have myths still—but they stream in high definition, flattened into entertainment.

We have temples still—but they are shopping malls and fitness centers.

We have rituals still—but they are routines, automated and optimized.

We do not lack information: we lack orientation.

We are not post-collapse.

We are mid-pattern.

And the question Plato asks—softly, symbolically, urgently—is this: Will we remember in time?

V. The Remnant

But not everything was lost.

Atlantis vanished. Athens too. The flood stripped away not just temples and towers, but names, deeds, lineages. There were no survivors, the priest says—at least not in flesh.

But something did survive.

Memory.

Not intact. Not in Greece. But in Egypt; in ritual, in symbol, in scrolls. And through Solon, it was passed on to Plato.

It’s easy to think of Plato as a philosopher, a builder of forms. But he lived at the threshold—between myth and method, between memory and system. He didn’t just reason; he remembered. His dialogues are full of stories, symbols, riddles, not just arguments but echoes.

He is what survives when a tradition dies—not its temple, but its soul.

And through him, something older flows forward.

Egypt wasn’t just the setting for this story. It was its source. The Greeks themselves admitted it: Pythagoras studied in Egypt. So did Solon. So, perhaps, did Plato.

Much of what we call Western thought passed through Alexandria—where Greek philosophy, Egyptian cosmology, and early Jewish and Christian mysticism coexisted and entangled.

The Hermetica, attributed to Thoth—or Hermes Trismegistus—carried echoes of both traditions: rational in form, mythic in soul. Even the very idea of the philosopher as priest, of knowledge as spiritual discipline, may have come not from Athens—but from the Nile. From rituals, not just reason. From myth, not just method.

Plato and his allegories stand between worlds—between the mystery schools and the laboratory, the initiation and the experiment, between the temple and the academy.

Behind the clear marble of Greek reason stands the dark stone of Egyptian memory.

We inherit both. Even if we only remember one.

He wasn’t trying to prove Atlantis existed. He was trying to preserve its meaning—and its warning. Atlantis was not a lost continent, it was a lost possibility. And Plato, by recording it, saved not the city—but the choice.

Because every time the pattern begins again, the memory offers an alternative.

You don’t need ships or spears to resist Atlantis.

You need remembering.

In every collapse myth, someone survives. But the survivors are not always powerful. Often, they are the ones who carry the story. Who rebuild not the walls, but the words.

And if you’re still reading—maybe that’s you, Slick.

Maybe the memory didn’t die; maybe it’s just been waiting. Maybe remembering is what survives the flood.

And what survives the flood becomes the seed of the world to come.

VI. The Temple and the Stairs

The echo of Plato’s memory still rings in stone.

It leaves no path—only stairs.

We live on the rock now. The fertile lands are gone. The rivers, dry. The gods are quiet. But the temple still stands. And the stairs are still there.

The sacred hasn’t vanished. It has gone still. Dormant. Waiting. It no longer roars from mountaintops or speaks in thunder—but it stirs in half-forgotten stories, in dreams that ache with symbols, in the yearning for a world more whole than this one.

We still carry myths. Not as laws, but as questions. As mirrors. As seeds. And perhaps that’s what remembering is: not the return of the past, but the return of depth. Of weight. Of meaning that reaches below the surface.

Atlantis isn’t a warning from the past. It’s a reflection of the present.

And memory is how we learn to see through the mirror.

Plato didn’t offer a utopia; he offered a memory, a myth.

And the courage to ask: what if the flood is not the end, but the clearing of ground?

The chance to plant something older—and new?

The stairs remain. No one is coming to carry you up them. But you can still climb.

And at the top: silence. Stone. Maybe a whisper. And in that whisper, the first syllable of a new world.

Spoken aloud.

Again.

After the flood, what matters isn’t what we saved.

It’s what we choose to plant.

We do not need to escape collapse. We need to carry memory through it. Not to preserve the past, but to plant the future.

We’re not here to rebuild the ruins. We’re here to plant from memory.

Atlantis isn’t lost.

It’s becoming.

Always a pleasure to read, I hope you find your comeuppance in due course!

I've been contemplating about Atlantis for a good few years now (Graham Hancock got me started on this long forgotten paths when I was a stoner back in the late 90s).

I agree with your interpretation that ultimately it's a story about remembering the future. And I agree with your interpretation of where we are atm.

My conclusion is slightly different though. A few years ago I came across a YT channel 'suspicious observers' who present a compelling case for regular cataclysmic pole shifts every 6/12k years. Every 12 is big, every 6 is small. It sort of fits with Sumer starting in 4k bc and the younger dryas 10.5/12k bc. 100 years is a fraction of 12k etc.

Obviously we're talking sci-fi as I like to premise these days. But if we take a starting point for homo sapiens at 350k, then we're around 30 cycles in, give or take.

So then, since we're talking sci-fi, I think about the agricultural, industrial and technological revolutions, all the way up to now. And I think, what gives, why now?

And I figure one explanation could be we're in a fish tank sand box kind of thing. And they (whoever they are) thought, well, them humans obviously have clearly fumbled the ball, again, so to speak, and the sphere will reset anyway, so let's see if humans can find a way to figure it out this time before the next inevitable wipeout and restart.

Obviously AI and robotics and what not could create a utopia, but realistically, we haven't been able to sort out the mechanics of a harmonious virtuous peaceful human sociopolitical life, becoming instead victims of our own narratives about life and labor and taxes and pensions and private property and money and power, etc.

Personally looking out ten or twenty years, I have a hard time imagining a future beyond the mental retardation currently going on, coupled with the inevitable fragility accompanying complexity.

Just food for thought.

Great essay, thanks!

Speculative, but in the company of Sigmund Freud who argued that Moses was probably an Egyptian who had learned about monotheism from Akheneton.