The Poet of Becoming: Freedom, Fiction, and the Soul After the Death of God

A guide for those who’ve outgrown belief, outlived irony, and still ache for meaning

“You ask to be free, my brother. I ask you not what you seek freedom from, but what you seek it for. To what end shall your freedom fly?”

-Nietzsche, ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’ (paraphrased)

Hey, Slick!

I didn’t plan to write this.

But I had to.

A trusted friend (thank you, Damilya!) shared a line from Nietzsche—the one quoted above, the one about freedom—and offered it as a challenge.

The kind of question that doesn’t let you go…

What are you for—not just against?

I realized I had left you in the ruins.

We’d dismantled the myths, traced the collapse, named the gods that failed.

And then left you there—in the cold, in the dark—with no way forward. No truth, no system, nothing to carry.

This is that offering.

Not a final truth. But the only place I know to begin.

Because today, I’m going to tell you something I probably shouldn’t...

There is no truth.

No final, absolute truth handed down from on high.

No truth that will save you.

And I’m not offering you salvation, either.

But if you’ve already seen through the promises—truth, progress, transcendence—

then maybe what I have is what you’ve been looking for.

Not comfort. Not answers.

Not salvation.

Soul.

Not the soul of dogma or doctrine. The soul as depth, as image, as the part of you still longing to feel.

And maybe—if it fits—a fiction worth living.

I. Prelude: After the Fall

You’ve stepped outside the cage.

The door was always open. But now you’ve walked through it.

No more gods watching. No commandments. No algorithms deciding what you see, think, or desire.

You thought freedom would feel like flight.

Instead, it feels like falling.

Outside the cave, the shadows are gone—but so is the fire.

Now you’re standing under a starless sky, and you feel the breath of empty space.

It has become colder, and night is continually closing in on you.

There are no pillars, no cosmic architecture, no story written in the heavens.

You walk through the ruins of what once held you. Doctrine. Destiny. The dream of progress.

The columns are cracked; the altar is empty; the sacred scripts are dust.

You pass the burnt library, the empty church, the broken lab.

You pick through the rubble, not for relics, but for reminders that you once believed.

You were disillusioned; and then disillusioned with disillusionment, too.

Even the comfort of cynicism has faded. You’re not angry; just awake.

This is the ache of post-cynicism: when irony fades and nothing rushes in to replace it. You’re beyond belief and disbelief—and it’s lonelier than you expected.

This is what freedom looks like when the myth breaks: not a wide open field, but a quiet reckoning.

Not a sunrise, but a long dusk.

And this is where Nietzsche meets you.

In a previous piece, How to Train a Superhuman, we explored the descent: the breaking of false truths, the confrontation with inner and outer authority, the spiritual battle to reclaim your own consciousness. That was the crucible.

This is the return.

If liberation is real, then what do you do with it? What will you live by now that you know every truth is a fiction, every story is a metaphor, every god a mask?

This essay is a search for that answer. Not a final one—but a myth you can carry.

II. The Inheritance of Illusion: Platonism and Its Descendants

“Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us?”

-Nietzsche, ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’

That was Nietzsche’s madman, shouting into a world that had already stopped listening. He had come to announce the death of God—not just the fading of belief, but the collapse of the sky itself. And no one understood the gravity of what had happened.

The death of God wasn’t just theological. It severed the great chain of being, the cosmic grammar that told us who we were, what we should do, and why it mattered.

We had already stopped believing—but we hadn’t yet understood what we had lost.

The gods are dead. The sky is empty. But their architecture lingers.

This is where Nietzsche begins his critique—not just of Christianity, but of the deeper structure beneath it.

Nietzsche called Christianity Platonism for the people, and not as a compliment. What he meant was that both traditions share a structure—a split between two worlds:

A higher, eternal, pure realm; the world of Being, Ideas, Heaven.

A lower, temporal, corrupt realm; the world of Becoming, Shadows, Sin.

This metaphysical split became the psychological architecture of the West. It taught us to distrust the body, to devalue appearances, to hunger for transcendence.

But what happens when faith in the “higher realm” collapses?

Nietzsche answers: nihilism.

Nihilism is not the betrayal of Platonism, but its final fruit. Once the promise of the true world dies, the only thing left is the world we were taught to hate.

Values derived from beyond life can only survive as long as belief in that "beyond" does. Without it, we are left disoriented, weightless, drowning in relativism or craving new dogma.

But Nietzsche doesn’t stop at diagnosis. He offers a path forward, not through return, but through creation.

III. Reading the Traditions as Mythic Grammars

Even in ruins, the old stories still shape us. We carry their grammar in our bones.

So before we write the future, we must listen to the myths that shaped us.

Nietzsche rejected the great spiritual traditions of the West—Platonism, Christianity, Gnosticism—not because they aimed too low, but because they aimed elsewhere.

They taught us to look beyond this world, beyond the body, beyond becoming.

They promised transcendent truths, handed down from above, that demanded submission—not participation.

But what if they were never meant to be read that way?

What if the traditions Nietzsche condemned were not wrong—but demanded a different kind of reading?

What if they were never meant to be metaphysical blueprints—but psychological grammars, symbolic systems, soul-maps?

We often dismiss these traditions as superstitions or failed philosophies. But what if above and below were never meant to describe geography, but states of being? What if gods and demons weren’t literal beings, but metaphors for inner forces? What if these systems, read with soul, still have something vital to offer?

Let’s return to four of these traditions—not as believers, but as translators of their inner terrain.

Platonism teaches that beyond the world of appearances lies a perfect, eternal realm: the world of Forms. This higher realm is real; everything else is its shadow. But what if the Forms were not things out there—but aspirations within? What if the world of Forms is a metaphor for the psyche’s longing for structure, wholeness, and meaning? Plato’s cave, then, becomes not a cosmology—but a portrait of inner awakening.

Neoplatonism describes the soul’s journey back to the One—an ascent through layers of being, away from multiplicity and toward divine simplicity. But what if that ascent isn’t a rejection of matter, but a deepening of attention? What if the One isn’t a god above, but the still point within—the hidden centre of coherence beneath chaos? In this light, Neoplatonism becomes a map for inner integration, not withdrawal.

Gnosticism claims that the world was made by a false god, and that we are divine sparks trapped in a prison of illusion. Salvation comes through secret knowledge—gnosis. But what if the archons are not cosmic tyrants, but the internalized voices of despair, conformity, and false identity? What if the demiurge is the ego’s insistence that this is all there is? Then gnosis becomes not escape, but the awakening to a deeper, freer self—the part of you that remembers something lost, and dares to reclaim it.

Hermeticism declares, “As above, so below.” It sees the cosmos and psyche as mirrors, and the goal as transformation—through image, ritual, and alchemy: the sacred art of turning what is base into what is noble. But what if alchemy was never about gold? What if it was always about the transmutation of the soul? Turning pain into presence. Turning fragmentation into form. Hermeticism then becomes not magic—but mythic psychology: the art of co-creating meaning with a living world.

These are not failed sciences; they are mythic grammars. And if we read them that way, they have much to offer those navigating the symbolic desert of modernity.

These myths don’t return us to belief—they ready us for something else. They prepare the ground for the one who dares to build with broken symbols.

And with these images in hand, we turn again to Nietzsche—not to destroy, but to create.

Not answers, but images; not instruction, but resonance. These are the forms the soul speaks in.

IV. Nietzsche’s Turn: From Destroyer to Creator

The myths have collapsed—but something in you still wants to speak.

Nietzsche’s answer to nihilism is not regression, but affirmation. The solution to the collapse of inherited meaning is not despair, but artistry.

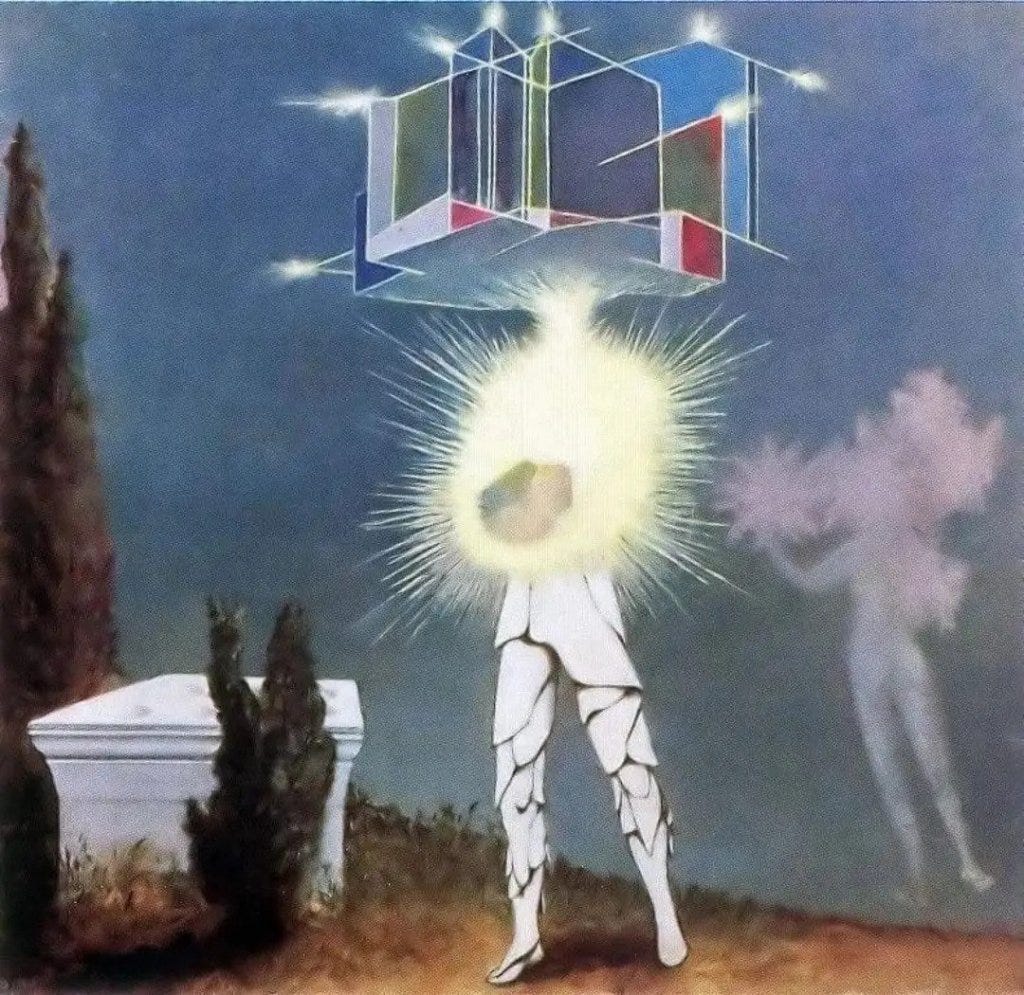

Enter the Übermensch.

Not a master of others, but of meaning.

Not a conqueror of worlds, but a crafter of values.

The Übermensch is not the end of man, but his overcoming.

He sees that the scaffolding has collapsed—and chooses to build anyway.

Not because he knows the truth, but because he knows truth is made.

Not to deceive, but to live as if the world still deserves a song.

This is the Nietzschean artist: the one who shapes new metaphors in full awareness that they are fictions—but fictions worth living.

This is the poet of becoming: not someone who escapes illusion, but one who shapes it consciously, beautifully, and responsibly.

This is the highest freedom—and also the most dangerous.

Because once you are the maker of values, there’s no one left to blame. No priest to obey. No system to hide inside.

Only you—and the myth you’re willing to carry.

V. Psychology After Metaphysics: Jung and Hillman

Jung picks up where Nietzsche leaves off. He sees that meaning doesn’t disappear when the gods die: it migrates inward.

Symbols are not superstitions. They are the language of the unconscious. The archetypes are not fantasies—they are structures of experience. Jung’s path of individuation is not a return to cosmic certainty, but a confrontation with inner contradiction—an alchemical process of becoming whole through shadow, symbol, and self-creation.

Hillman radicalizes this: he rejects the heroic ego, the quest for unity, the idea of the psyche as something to be solved. Instead, he invites us to see psychology not as science, but as soul-work—an act of imagination.

Where Jung sought integration, Hillman embraces complexity. He sees the psyche not as a single, unified self to be uncovered, but as a chorus of myths, moods, and images—each with its own voice. The goal is not to fix the soul, but to tend it, to listen, and to imagine with it.

The soul, he says, is polytheistic. Plural. Deep. Contradictory. It speaks in images, not ideas.

“We do not interpret myths psychologically. We interpret psychology mythologically.”

-James Hillman, ‘Re-Visioning Psychology’

In Hillman’s terms, the goal is not wholeness, but richness. Not truth, but resonance. Not resolution, but the ability to live inside tensions and symbols without needing them to resolve.

This is not so far from Nietzsche. The Übermensch and the soul-maker are both working without guarantees; both are stylists of meaning.

Soul-making, as Hillman understood it, isn’t a cure—it’s a cultivation. A descent into the images, wounds, and contradictions that make us fully human.

But in a world without shared myths, what do we build with? What images remain?

VI. Living Inside Fiction: The Metaphors We Carry Now

If the old metaphysical myths have died, what has replaced them?

Neil Postman tells us: new metaphors. New media. New myths.

“The medium is the metaphor.”

-Neil Postman, ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death’

McLuhan said, “The medium is the message.” What he meant was that the form of communication—television, print, the internet—shapes the nature of what is said, often more than the content itself. Postman sharpened the point: the medium is the metaphor. Every form of media doesn’t just deliver content—it shapes how we think. It teaches us what is real, what is valuable, what is worth aspiring to.

So if the old gods once spoke from burning bushes or sacred texts, today they arrive through algorithms, interfaces, and content streams. The myths have changed. The medium has changed. But the shaping hasn’t stopped.

We live through structures of sense. But today, those structures are fragmented, commercialized, disenchanted. Still, they function as our living fictions; here are five myths you may already be living—without ever noticing you subscribed.

The Quantified Self. You are your data; optimization is salvation. Identity is reduced to performance; every part of you becomes measurable, improvable, marketable.

The Eternal Seeker. Always healing, always upgrading, never arriving; always working on yourself, yet never quite home. Growth becomes the goal of growth. You’re never quite enough, but always almost there.

The Original Wound. I am what was done to me; the past is the only truth. Trauma becomes identity; healing becomes repetition. Nothing matters more than what hurt you.

The God of the Machine1. What can’t be solved hasn’t been coded yet. Mystery is inefficiency, the soul an engineering problem, and design is destiny.

The High Priest of Irony2. Nothing is real—and I’m smarter for knowing that. Belief is cringe; meaning is suspicious; sincerity is for suckers.

These are myths, too, but we rarely recognize them as such—and that is where the danger lies, Slick.

Postman’s deeper provocation is this: everything is a metaphor. Not just art, not just myth—but every structure of meaning we inherit or invent.

This doesn’t mean truth is dead. It means truth is always carried in metaphor. Even science, even objectivity. A scientific paper is not just facts—it is a ritual of credibility, a genre of persuasion, a narrative clothed in charts and citations. Once the myth of pure neutrality breaks, we’re not left with nothing—we’re left with everything cloaked in fiction. The question is no longer whether we live by stories, but which ones.

VII. The Shadow of Choice: When Your Fiction Deceives You

To live mythically is not to escape illusion. It is to choose it consciously.

But not every fiction deepens the soul. Some flatter the ego; some seduce us into simulation, transcendence without descent, power without grief.

This is where Silicon Valley spirituality goes wrong. It sells you godlike freedom—without initiation. It promises elevation, without weight.

This is the spiritual costume that cynicism wears when it’s not ready to become soul. Hungry for meaning, but unwilling to suffer for it. Beyond belief—but not yet ready to believe again. Cynical about transcendence, but desperate for it.

It is not alone. Some fictions heal; others hollow. The danger is not living by myth—it’s mistaking anesthesia for depth.

So how do you know if your chosen fiction is soul-making—or just self-soothing?

There will be signs, Slick…

A soul-fiction doesn’t offer escape or distraction from pain—it deepens your capacity to suffer. A false fiction offers relief from suffering, but only by bypassing it.

A soul-fiction connects you to others; a false fiction isolates you in superiority.

A soul-fiction includes shadow, grief, and paradox. A false fiction demands purity, control, or light.

A soul-fiction returns you to the world, cracked open. A false fiction lifts you above the world and leaves you there.

A soul-fiction asks you to serve something beyond your ego. A false fiction centres your exceptionalism.

This is the task of post-cynicism: not to pretend again, but to choose better illusions—ones that make us more human.

Ask yourself:

Does my fiction bring me closer to complexity, or simplicity?

Does it open me to others, or shield me from them?

Does it help me live, suffer, and love more deeply?

To become the poet of becoming is not to escape pain. It is to suffer it on purpose, in rhythm, in meaning.

This is myth as discipline, not fantasy.

VIII. What Is Your Freedom For?

You met Nietzsche in the ruins. And here, at the end of the long dusk, his question returns—and you carry its weight.

You are free now.

Not because truth has been revealed, but because you know it never will be. The Sun may not rise again—but you can light your own fire.

You have a pen now. Not a map.

The gods won’t return, but something waits for your signature.

Not to prove you’re right—but to prove you’re real.

Live as if it matters—that is the task.

This is what it means to become a soul-maker, a value-creator, a myth-weaver. You do not escape metaphor: you choose it.

And you carry it with the weight it deserves. As if it were sacred, because it is. And you walk with it into the world.

But hold this, Slick: not every myth must be invented. Some are inherited, whispered, dreamt.

The work is not only to create, but to consent—to be shaped, too.

Some fictions find you. Some stories carry you.

Even the poet must first listen, be a vessel, be not always the weaver, but be woven sometimes.

IX. Conclusion: Choose Your Fiction Well

This is the work of post-cynicism3: not to return to belief, but to create with care.

You stepped outside the cage. You stood beneath the starless sky. You wandered through the ruins.

You learned that the myth does not return to you.

You return to it—deliberate, wounded, awake.

You are already living inside a fiction.

The only question is: whose is it?

You cannot step outside metaphor, but you can step deeper into the one that calls your name.

Choose one that cracks you open. One that holds your shadow. One that does not lift you above the world—but drops you back into it with more ache, more care, more soul.

Become the poet of your becoming—that is what your freedom is for.

Oh, hi, Curtis Yarvin!

I believe that’s us, Slick? The post-cynical. A stage after disillusionment and after irony, when one has stopped believing in the myths and stopped feeling clever for doing so. A mature response to collapse: not nihilism, not naïveté, but a deeper, deliberate engagement with life, meaning, and story.

"In every age, in various forms, philosophers have defended their own independence and their resistance to the given world, saying that the aim of their knowing was freedom and not nature, spirit and not matter, value and not actuality, meaning and not necessity, essence and not appearance. Philosophy, like every creative act, strives toward the transcendent, towards passing beyond the borders of the given world. Philosophy does not believe that the world is really like that which is forced upon us by necessity."- February 1914, Nikolai Berdyeav-"The Meaning of the Creative Act".

"Science has no visions of freedom in the world. Science does not know the final secrets because science is knowledge without danger. Hence science does not know Truth but knows only truths. The truth of science is significant only for partial conditions of being and for partial orientations within it. Science makes its own reality." - Ibid.

"Life, and all that lives, is conceived in the mist and not the crystal. And who knows but a crystal is mist in decay?"

(The Prophet)