Hey, Slick!

This is the third and final letter I’m sending you on vampires.

In the first, we stood in front of the mirror and found the vampire staring back—our shadow self, our hidden desires and fears.

In the second, we followed the vampire’s trail out into the world, where they slipped from castles into boardrooms, draining society through power, greed, and exploitation.

But after all this hunting, there’s still one thing we haven’t found, Slick.

A cure.

If vampires are mirrors, they show us the problem—but they don’t show us the way out. That’s why we’re leaving the velvet curtains and candlelit halls behind.

The vampires we’ve hunted so far—Dracula, Lestat, the Cullens—mirror our inner fears and societal predators. But if we want to break the curse, we need to look elsewhere. The cure doesn’t come from the castle; it’s out in the wild, where ancient myths of vampirism tell stories not just of monsters, but of remedies.

There’s a word you’re about to meet: Wetiko1. Like a whisper through the trees, a name that carries a warning—and maybe a remedy.

But the Wetiko isn’t alone. Other myths, from other cultures, echo the same fears: a life-draining force, a hunger that corrupts, a darkness that spreads through more than just one person and infects entire communities.

These stories don’t just warn us about what happens when an individual succumbs to greed or exploitation: they reveal how these dark patterns become systemic, how they warp our relationships and societies. And they hint at a way out, a path back to humanity—if we’re willing to take it.

We’ve seen the shadows in our minds, and the vampires in our world. Now it’s time to step outside those shadows and into the forests of North America, the mountains of China, and the coasts of the Caribbean.

So let’s go hunting, Slick. The cure is out there.

Different Fangs, Same Curse: Vampires Around the World

To find it, we’re stepping beyond familiar shadows.

This isn’t a detour into folklore or a list of exotic creatures tacked on for flair in a footnote. We didn’t save these global myths for the end because they’re secondary; we saved them because they might save us.

From the Aswang of the Philippines to the Jiangshi of China, different cultures have long grappled with the fear of being drained, consumed, or corrupted. These myths reflect universal anxieties about greed, exploitation, and the loss of humanity.

The Aswang are shape-shifting predators that target the vulnerable—particularly children and pregnant women. They capture fears of betrayal, sickness, and societal collapse.

Much like the Chinese Jiangshi. The infamous “hopping vampires” suffer from rigor mortis and hop around, arms stretched. Rather than sucking blood, though, they drain the life essence (Qi) of the living.

Why do some people become Jiangshi? Sometimes it’s because they weren’t buried properly, reflecting the cultural importance of ancestor veneration and tradition. But others return from the dead because of unfulfilled desires, grudges, or immoral living—a warning that greed and trauma can linger long after death, and a curse closer to the vampires we know.

The Indian Vetala2 is not the corpse returning, but the demon that inhabits and animates it and goes around tormenting the living and driving them mad.

The Vetala is a cautionary tale against unfulfilled desires and unresolved karma, or what happens when life’s ambitions, grudges, or moral duties are left incomplete, while capturing fears of losing control over our body and mind.

And then there’s the Loogaroo3, a Caribbean syncretistic vampire blending French, African, and Indigenous Caribbean beliefs. The name comes from the French loup-garou, or werewolf, but the Loogarou is more of a shape-shifting vampire.

Initially, though, the Loogaroo was just an elderly woman, who made a pact with the devil for power or longevity. In return, she has to provide blood. So at night, the Loogaroo sheds her human skin, and transforms into a creature or a ball of light, and feeds on the blood of others.

The Loogaroo betrays her community, putting short-term power over long-term integrity, and the myth reveals anxieties about internal betrayal and exploitation within close social circles.

You may already sense a theme emerging, Slick: to avoid turning into vampires, we may want to live with integrity, honour our connections, and practice selfishness and betrayal in moderation.

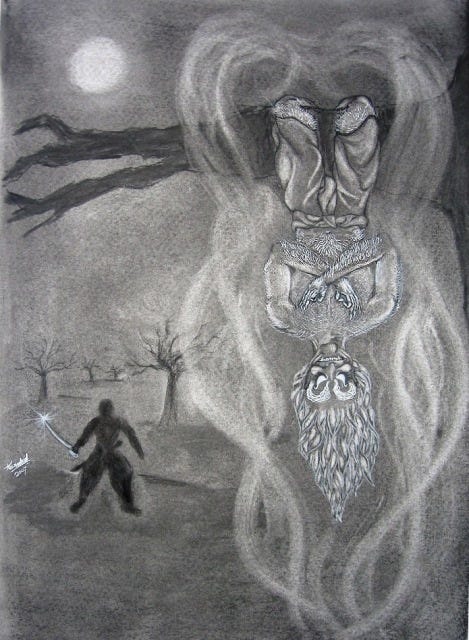

But let’s go further West still, deep into the forests of North America and their long, harsh Winters. In these forests roams a gaunt, skeletal figure, with glowing eyes and decaying skin - and an insatiable hunger: the Wetiko.

I, too, would rather stay far away, but this fearsome monster holds the cure, so we’ll stick around.

Wetiko: The Hunger That Never Ends

A supernatural creature from the folklore of Algonquian-speaking tribes4, the Wetiko is associated with cannibalism, greed, and moral decay.

Those who prey on others, even during desperate times—who steal or consume without regard (including cannibalism)—transform into Wetikos. Forever cursed, they wander in a state of eternal hunger, never satisfied, no matter how much they devour, much like the Hungry Ghosts of Buddhism.

The Wetiko symbolizes more than personal greed. It represents what happens to societies driven by consumption. A community infected by this hunger turns against itself, draining resources, devouring trust, and eroding bonds of empathy.

The Wetiko thrives when people see others as prey—when exploitation is normalized, and the line between survival and predation blurs.

Sounds familiar?

The Wetiko, through acts of desperation and corruption, has let base instincts override ethics, and lost its humanity. Now, it is doomed to wander alone, cut off from human connection and community. The Wetiko suffers the ultimate consequence of greed: alienation and spiritual decay.

But the Wetiko isn’t just a cautionary tale of monstrous greed; it offers a path back to humanity.

Wetiko and the Path to Redemption

In examining the Wetiko myth, Indigenous author Jack Forbes draws powerful parallels between the Wetiko and vampires. Both represent the dangers of unchecked consumption, greed, and moral decay. But Forbes also identifies a cure.

The first step to healing is to accept you are a vampire. That there is an insatiable hunger within all of us, that we all have the potential for greed, exploitation, and selfishness.

Without this awareness, we risk becoming the very monsters we fear.

”Hi, my name is Slick, and I am a vampire.”

Second, in a world that constantly tells us to consume more, full of Glamour and Discourse, practicing restraint and generosity - choosing to share, help, give back - is an antidote to the endless hunger that drives vampirism.

Lastly, the Wetiko, and vampires in general, thrive in isolation. The cure also lies in reconnecting with community, empathy, and solidarity; in shifting from a predatory mindset to a humanizing one.

This means more than avoiding isolation - it means actively engaging with others in a way that honours their humanity. Vampires see others as mere sources of sustenance, reducing them to prey. The cure lies in reversing this dynamic: treating others not as objects to be consumed, but as individuals with their own desires, stories, and needs.

By practicing empathy, we move beyond the predator-prey relationship that defines vampirism, and embrace true connection. It’s in this space of mutual respect and care that we find healing and, ultimately, redemption.

Timeless Myth, Timeless Wisdom: Why Vampires Never Die

Will we ever get rid of vampirism, Slick?

I don’t think so.

The vampire myth is universal and timeless because it speaks to dangers that are universal and timeless. Across cultures and centuries, vampires have warned us about exploitation, greed, and the darker sides of human nature. Whether it’s the Jiangshi draining life force in China, the Wendigo warning Algonquian tribes against greed, or Dracula haunting Victorian England, the message is the same: avoid the shadows, face the truth, and stay connected to what makes us human.

Vampires endure because they remind us of what we fear most—and offer us the chance to confront it. Whether through cultural rituals, self-awareness, or re-humanization, the vampire teaches us how to reclaim our humanity, no matter where or when the story is told.

“But there was no reflection of him in the mirror! The whole room behind me was displayed; but there was no sign of a man in it; except myself.”

-Bram Stoker, Dracula

The global myths - from the Vetala to the Loogaroo, the Jiangshi to the Wendigo - all point to the same truth: the cure for vampirism is not found in stakes and garlic, but in our actions and choices.

So, Slick, we’ve come full circle. Vampires are a mirror. They reflect our shadows—our greed, our fears, our desires for domination. But they also show us the way out. By looking deeply into that mirror, by confronting the vampire within, we find the power to break the curse.

To cure vampirism, we must embrace the things vampires fear most:

Shine the light: The light of truth, self-awareness, and exposure.

Look in the Mirror: Look deeply, confront your darkness, and reclaim your soul.

Stay connected: See others as people, not prey. Choose to reconnect with humanity instead of feeding on it.

Vampires drain life; humans nurture it. The cure for vampirism is not in destroying the monster, but in reclaiming the human.

In seeing each other, not as prey or rivals, but as fellow travellers in the dark—holding up mirrors, and carrying the light.

In choosing life over exploitation, connection over isolation, awareness over denial.

In other words, the cure is to be fully human.

So, Slick, the next time you look in the mirror, don’t just check your reflection - make sure you can also see your own shadow. Reflect on your humanity. Because the vampire isn’t inevitable; the cure is always within reach.

Until then,

Stay Slick

or ‘Wendigo’

Vikram and the Vital, in Kathasaritsagara, 11th century

or ‘Rougarou’

particularly Ojibwe, Cree, and Algonquin people