Router, Bait-and-Switch: A Eulogy for the World Wide Web

What happened to the Internet we were promised?

Hey, Slick!

What happened to the Internet?

No, seriously. Why did we build a giant mall over cyberspace, with cameras everywhere and a cop at the entrance checking IDs?

There was a time, not long ago, when ID checks were a privacy punchline.

What’s next, an Internet driver’s license?

Today they’re not so outlandish. A UK court is moving to end pseudonymity on Wikipedia, YouTube and Spotify are following suit, and the Supreme Court has backed ID laws in Mississippi and Texas.

And as it’s happening, we’re more preoccupied with ChatGPT-5 than with the fate of good ol’ Wikipedia, an Internet dinosaur, or further surveillance by the platforms that once heralded the Web 2.0.

This was not inevitable, and not an accident either. The Web was born in freedom, but over thirty years it was remade into a mall, a prison, and a circus.

The warnings were there from the beginning. But if you raise the water temperature slowly, the frog stays…

So mourn with me, Slick, for the Internet that could have been. And let’s see what lessons its ruins still have for the future.

I. Free Unlimited Internet

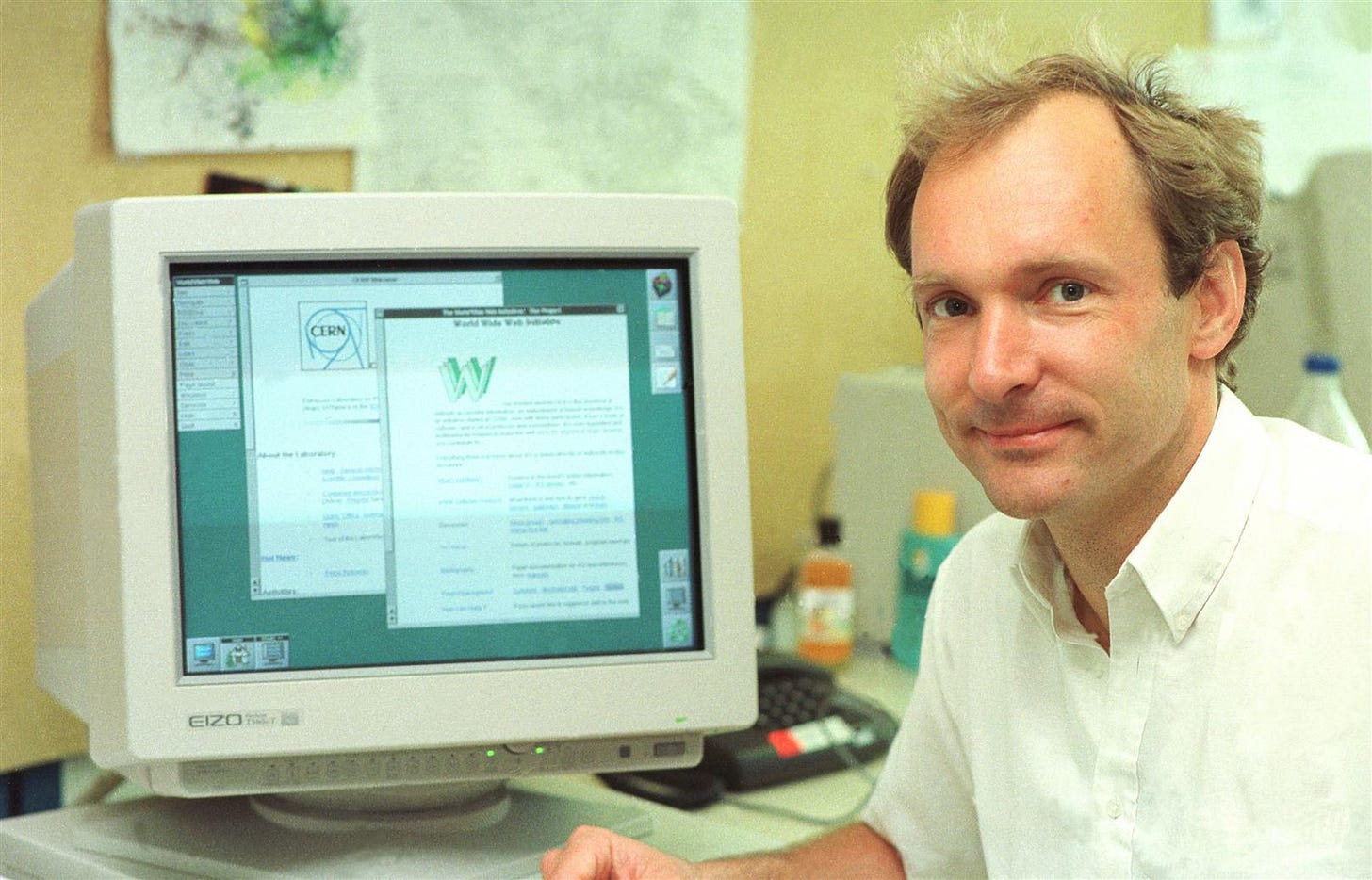

In the early days, people had all kinds of visions for the World Wide Web and the highways of information. Cyberspace was a new frontier, full of wizards and dreams. In 1989 Tim Berners-Lee imagined the web as a universal, open protocol, and later summed up the ethos: “This is for everyone.”

The Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace captured the cyber-optimist ideal of an open, decentralized utopia, free from the grip of governments and corporations:

“Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel […] You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

—John Perry Barlow, A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace (1996)

The Web would create a civilization of the Mind.

It would connect the whole world to all of human knowledge.

It would empower people to learn anything, share anything, connect with anyone, anywhere.

It would tear down barriers and borders.

The cyber-optimists dreamed of virtual cities and digital republics built on a radical architecture, open and free by design. The web was based on open protocols1 that nobody owned and anyone could use; domain names and addresses were entrusted to a ’neutral’ steward, ICANN. Anyone could have a server or write an application. No gatekeepers, no central chokepoints; the Web was built end-to-end, a network that only carried packets, keeping the control at the edge, in the user’s hands.

The vision was grand. By today’s standards though, the Internet that loaded on your beige desktop monitor was underwhelming. It was slow; you’d have to wait for the modem to be done with the weird gargling sounds, for pages to load and images to crawl into existence line by line. And you couldn’t use the phone at the same time.

But it felt infinite, untamed, user-built. You would find information on the care and keeping of a pet snake your local library didn’t have on some hobbyist’s HTML website, and it didn’t have ads, it didn’t have an ebook to sell or a tracking pixel. It was just there.

Information hadn’t become content yet. It wasn’t optimized for stickiness or engagement. No one had invented UX dark patterns and the infinite scroll.

“Information wants to be free.”

— Stewart Brand

It looks very different now. In ways, the World Wide Web did deliver on the dreams: it gave us instant communication, endless media, global connection. But not exactly as expected. The Internet is a place where people gather, but not quite like the new town hall, the library and the virtual university the cyber-optimists envisioned.

They underestimated how quickly and radically the Internet would be transformed when billions of users and dollars poured in, and governments and corporations colonized it at warp speed.

II. The Betrayals

The dream was virtual cities and digital republics. The reality is more like the stuff of cyberpunk dystopia: part mall, part prison, part circus.

The Mall: the Cost of Free

We entered the mall enthusiastically, attracted by the freebies: free email, free storage, free apps. After all, the Internet was supposed to be free.

But, as Richard Stallman warned, that meant “free as in freedom, not as in beer”. The real cost was our attention and data. Free was funded by ads, and ads sold best when platforms knew everything about us. Surveillance capitalism was born. Users became the product, and the mall became the Internet.

The “free beer” model wasn’t inevitable. It was engineered. Venture capital subsidized growth until competition was gone, startups blitz-scaled into monopolies, and users were locked in. The service got worse as the focus shifted from users to advertisers, then to shareholders. The Internet gave us many new words, and enshittification2 had to be one of them.

Platforms didn’t just sell ads. They changed the Internet. In cyberspace, architecture governs: code is law.

“This code, or architecture, sets the terms on which life in cyberspace is experienced. It determines how easy it is to protect privacy, or how easy it is to censor speech. It determines whether access to information is general or whether information is zoned. It affects who sees what, or what is monitored. In a host of ways that one cannot begin to see unless one begins to understand the nature of this code, the code of cyberspace regulates.”

—Lawrence Lessig, On Liberty in Cyberspace, 2000

At first, platforms were neutral. Section 230 gave them immunity for user content. But neutrality didn’t last: first they curated content for advertisers, then moderated fake news and hate speech. Now their billionaire owners openly set the boundaries of speech.

But the mall was only the first betrayal. Surveillance wasn’t just for profit; it became the rationale for turning the Web into a prison. Citizens had to be kept safe from criminals, terrorists, pirates, and pedophiles. Before you read them, Google scanned your emails to keep them spam-free; the government scanned them to prevent attacks.

The Prison: Death by a Thousand Acts

If code is law, software freedom is inseparable from political freedom. That was the point of Richard Stallman and the Free Software Movement. But law also shaped the code, and the government didn’t stay out very long.

In 1994, CALEA mandated the same surveillance access to digital communications. The pipes had backdoors. Then came the war on online piracy. The DMCA (1998) criminalized circumventing digital rights management. It baked monitoring and restrictions into systems; spyware became common and normalized user-level surveillance to check what files you had or copied.

After that, it was 9/11 and terrorists. The PATRIOT Act lowered the thresholds for warrants and subpoenas, and allowed bulk collection of phone and Internet metadata. It made surveillance the norm. In 2013, Snowden revealed its true extent: the government wasn’t just watching suspects, it was spying on everyone, and the platforms made it easy.

“Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age,” the Cypherpunk manifesto warned in 1993. Each law and backdoor would be sold as ‘necessary’ and ‘limited’ but privacy would be chipped away, until the default was bulk data collection. But without privacy, there was no free Internet, not even a free society. Their answer? Encryption.

But that presupposes you’re in control of the machine.

The Circus: the War on General Computation

In 1985, Stallman’s GNU Manifesto predicted users would become tenants, not owners, of their own machines. And that’s exactly what happened.

Computers and code were increasingly locked down. Digital rights management spread everywhere, and bypassing it was made illegal. Software came with activation keys, phoning home to check if you were authorized. App stores took it further: you couldn’t just install software, it had to be approved. Slowly, the computer became a restricted device, and the phone even more so, in what Cory Doctorow later called the war on general computation.

But users lost more than freedom. They lost literacy. The early Internet was slow and clunky, full of little frictions. You had to install drivers, configure browser settings, tinker with HTML and plug-ins and servers. That inconvenience was part of the experience, and maybe of the ethos.

Platforms changed that. They had sleek interfaces, were easy to use, everything was streamlined for mass adoption. Plug-and-play became the norm. Netizens became less citizen-engineers and more passive “users”, viewers, performers. The content was still user-generated, but our posts, photos, and videos stopped building the web and started feeding the feed.

The platforms optimized for stickiness. Autoplay, TikTok loops, infinite scroll, dopamine-hit design were all features in an architecture of compulsion. And so the circus began, a circus that pacifies and polarizes at once. We dance, we clap, we binge, we rage; the clowns are us. Meanwhile the ringmasters monetize the show.

The Internet became a black box. Yet we see right through it. It's a mall, and inside this mall is an aquarium, and we are the fish.

III. Where we are now

The “free” Internet is gone. The enclosure is nearly total. The proprietary logic dominates, the Web is divided into walled gardens, and ID checks are mandated at the door. Even crypto changed from digital currency free from the hands of government to an asset you declare on tax returns, hold in a wallet you don’t control, and is turning into stablecoins backed by T-bills.

The World Wide Web is so ubiquitous it’s hard to imagine our lives without it, and it gave us great essays, weird art, and amazing cat videos. But compared to the early ideals, it’s quite a disappointment; Tim Berners-Lee expressed just as much 35 years on, in 2007. It didn’t turn out to be the engine of human flourishing that was promised.

Back to the Future

The Internet did deliver on the future, though. The future of 1984 and Brave New World.

In 1985, Neil Postman argued in Amusing Ourselves To Death that we were closer to Huxley’s Brave New World than Orwell’s 1984, more distraction and amusement than censorship and jackboots. At the time, he was concerned with television culture. The Internet pushed it further, and asked: why not both?

It gave us more Brave New World: sedated by TikTok and OnlyFans, isolated by social media that lets us be ‘alone together’3, polarized by echo chambers, filter bubbles and engagement loops. It’s rewiring our brains with shorter attention spans, skim-reading, and increasingly outsourced thinking, and reshaping our reality: the Internet is spectacle, simulation, and hyperreality in ways Baudrillard and Debord could hardly imagine.

And at the same time, it’s bringing 1984 back. The open architecture has turned into an architecture of control, and the privacy warnings of old have become headlines. The bigger danger is that we may see more unfold, and that it will be less fun than cat videos.

The data keeps flowing and aggregating, and it’s never been easier and cheaper to store, analyze, or even purchase. Already, ICE is buying data from brokers online to identify and locate migrants; no warrant needed, because anyone can buy the dossier. Meta builds ‘shadow profiles’ of people who never even signed up. Palantir sells predictive policing tools with record sales.

The panopticon was a metaphor, now it’s a product. It’s as close to dystopia as it gets, and even with all the sci-fi ever written, it’s hard to imagine all the impacts when the government, your insurer, your bank and HR know everything about you. If the history of the Internet teaches us anything though, it’s that what can be done will be done. The sci-fi that once warned us of predictive policing, like Minority Report and Black Mirror, now reads less like caution and more like documentation.

Can We Save the Internet?

Maybe the Internet can’t be saved from itself. Enshittification at scale becomes the Dead Internet Theory: bots talking to bots, AI training on AI slop, and human contributions dwindling. The Internet could become so boring or untrustworthy it’s not worth showing up for.

Why answer a question on Stack Overflow when ChatGPT will scrape it, strip your name, and regurgitate it?

Why write a guide when Google buries it under ads and AI snippets?

Why do anything when the AI can do it for you?

Stallman, the cypherpunks, even Berners-Lee himself knew a free Internet wasn’t guaranteed. Now, we know it never came.

Nothing in this trajectory was inevitable. Each step was a choice, and could have been different. The tech, the culture, the law, the business model could all have been different. What we got is the result of specific alignments between capital and governments, and our willingness to trade freedom for free beer.

And it still isn’t. We can and should still push back on total enclosure. ID checks are no more about safety than DRM, app stores and data capture were. Just the latest step to end anonymity and pseudonymity online, and turn the Internet into a policeable space where every action is tied to you. We know who you are. And everything about you. We were never citizens of the Internet; but now we are just citizens on the Internet.

The ideals of the Internet were inspiring, but the warnings aged better. Privacy, interoperability, the right to repair, and the right to run your own software are still needed for a free Internet. And arguably, they’ve become even more important now.

We won’t bring the old Internet back. But we don’t have to stay within the enclosure. We don’t have to be frogs slowly boiling in an ever-shittier mall aquarium. We can keep building in the cracks. The choice is simple: carve out spaces of freedom now, or get used to handing over your ID at the gate forever.

It isn’t just about not feeding the beast more than we must, it’s about protecting your own digital life, and your life in general, from the consequences of surveillance you may never even see. And there are also pockets of hope, where the spirit of the early Internet lives on. Signal, Mastodon, Matrix, open-source projects, and HTML websites about the care and keeping of your pet snake may be small, but they exist. I’ll put a few links at the end.

IV. The Wisdom of the Internet: Five Questions on Progress

The Internet didn’t deliver on the promises, but it delivers stark lessons in tech ecology. Technology isn’t inevitable, and it isn’t neutral. Just because you have idealist geeks and lofty dreams doesn't necessarily mean you'll get a free, open, decentralized cyberspace.

What does it do?

Like every new wave of technology, the Internet arrived wrapped in promises. But a system is what it does, not what it says.

The Internet promised connection; what it delivered was polarization, addiction, and surveillance. Social media was sold as a new town square; it turned into a dopamine slot machine and a tool for targeted manipulation. Tech enthusiasts still talk about the Internet like it’s 1999, as if the promises were intact.

The same thing is happening now with AI: it promises empowerment, creativity, liberation from drudgery, and delivers plagiarism at scale (LINK AI TEMU), the deskilling of human labor, and an Internet drowning in machine-generated slop. The lofty promises hide the way it’s built.

So we shouldn’t fall for promises. We should ask more questions about technology than ‘what can it do?’ or ‘does it work?’ and ‘what’s the total addressable market?’

What does it replace?

The first question we should ask of every tool or technology is not what it adds, but what it replaces or removes. Every technology displaces an older way of being human. And it happened even within the Internet’s own ecosystem.

Before Airbnb allowed everyone to monetize their spare bedroom (and later, to overhaul the market in large cities), there was Couchsurfing, where you hosted or stayed with strangers, for free. It wasn’t efficient; there was a lot of serendipity involved, the process was full of friction, and you couldn’t just instant-book a stranger’s couch. But you got to meet them, and often to discover their city and their world and have deep conversations with people you trusted enough to share a space, even if you’d never meet them again. Online piracy may have been detrimental to artists, but Spotify doesn’t pay creators much more per stream than Napster did for every illegal download. AI might get you the answer faster than online contributors ever could, but it hollows out communities.

What values does it embody?

Every tool or tech encodes priorities. Not every tool is built the same.

Ivan Illich distinguished between convivial tools and industrial tools4: convivial tools enable autonomy, cooperation, creativity; industrial tools disempower, standardize, and create dependency. They turn people into consumers, not makers; enforce uniformity and scale, and make users reliant on centralized systems, experts, and bureaucracies.

The original values of the Internet weren’t the ones that won out. A network designed to be distributed turned centralized. A space of freedom became a system of control. Friction and serendipity were replaced by efficiency and standardization; communities and conversation gave way to platforms of performance and consumption. The convivial values faded; the industrial values triumphed.

Shifts are also visible not just in the tools, but in the culture of the people building them. The work culture of Silicon Valley itself is evolving; in the 2010s tech giant offered perks and marketed work-life balance, only to revert to hustle culture and the 996 grindset to win the AI race.

What does it make of us?

Tools and technology also shape us. We start to think in the shape of our tools.

“The medium is the metaphor.”

— Neil Postman

Television made us spectators. The Internet made us both performers and commodities, living to be seen and sold as data. A search query makes you an ad target; a post makes you content for someone else’s feed. We become passive consumers, or clowns in the circus of engagement. Our attention, our friendships, even our identities became ’fictitious commodities’5, packaged and traded.

The platform economy changed our role. We use more than we build, we perform more than we contribute. A civilization of citizens became a civilization of users: we use the Internet, and the Internet uses us.

What is captured, and what resists?

Tools and technologies don’t exist in a vacuum. They can be captured, and that’s exactly what happened to the Internet: governments and corporations didn’t stay away very long, and the highways of information turned into data dragnets.

In this way, the Internet is no different from previous technologies. Karl Polanyi described this as the ‘double movement’: markets push to commodify, and society pushes back. The Internet followed the same arc: what began as open and distributed was enclosed by platforms and states.

But enclosure breeds resistance. Free software, encryption, right-to-repair, Mastodon and Signal aren’t accidents; they’re the other half of the story. Some form of enclosure might be inevitable, but so are the cracks.

And cracks are where freedom grows.

***

There is hope: that we will become wiser, and adapt. The Internet is reshaping us in ways we haven’t had time to adjust to. Maybe we can make it better; maybe we can learn.

And at the very least, we can learn to be more discerning. Stop falling for the hype and the promises of progress or empowerment; that’s all technological bluff6. Technology comes with its own ideology and PR, and the costs are rarely discussed upfront.

Discernment is seeing tech for what it is, not what it claims to be; seeing what it does to us, not just for us. It’s realizing that technology isn’t necessarily progress.

It’s resisting capture, keeping the cracks alive.

As promised, here are a few links:

Defective by Design against DRM and digital locks

User-friendly, privacy-first browsers: Brave, DuckDuckGo, Firefox, LibreWolf

Messaging: Signal, Mastodon, Matrix

Further reading on privacy:

Wired on How to protect your data

Privacy-focused Substacks

TCP/IP, HTTP, SMTP

We owe the term to Cory Doctorow

Sherry Turkle

Tools for Conviviality, 1973

The term is borrowed from Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, 1944

Jacques Ellul

This is an important piece. You rightly began a conversation on AI. What you said we’ve learned from the Internet, if it can happen it will (paraphrased) should cause us to hit PAUSE on AI. But of course we won’t.

I meant to add something about the arrogance and lack of historical knowledge from lessons learned that now permeate the more serious, ethically-oriented insider publishing about how to get AI right. They think that if they just keep correcting AI hallucinations, and moral degradations they can teach it how to behave unerringly. This was already tried in the early 20th century by the idealist turn in linguistic philosophy, led by the most brilliant, formal logicians of their time, Bertrand Russell and Ludvig Wittgenstein. They thought they could make language into a system of communication, free of ambiguity and misunderstanding. They failed famously, because symbols are inherently ambiguous, and multi vocal, with multi-vocality being an open-ended, constantly evolving feature of symbolic communication. For AI architects to believe that they can get this fantasy right with AI is not only terrifying, it is historically, epistemologically, and methodologically ignorant. Yet, there is no stopping them. They are cocksure they will get it right. We will have to learn how to tame this thing if it is to serve authentic human interests, as you persuasively argue we must now do with the Internet. Thank you.