Jesus and the Doomsday Clock, part 2: the Katechon Catechism

How the “Katechon” Turned Emergency into a Theology of Power

Hey, Slick!

How did we get from the Sermon on the Mount and “turn the other cheek” to killer drones?

You would think they don’t belong together, but to some, they come as a package: a new apocalyptic state theology of the exception now shapes parts of U.S. tech and politics, recasting punishment as mercy and deterrence as discipleship. This catechism migrated from Paul’s riddle through empire and counter‑revolution into today’s U.S. security/tech imaginaries, where permanent emergency is preached as faithfulness.

So what happened?

We’ve looked earlier at the backstory of Christianity’s entanglement with power. Long story short: Christianity began as a minority church whose power was witness, not coercion. But after Constantine, the cross and the sword entwined, and the church joined the empire. Confessional states and divine-right monarchs followed; even the papacy, once the conscience of kings, fielded armies of its own.

The Enlightenment pried them apart, and much of modern Christianity edged back towards its original posture of witness: Catholic social teaching and Vatican II’s ‘Ressourcement’; subsidiarity and ’Just Peace’ theology.

But not everyone agreed. For some, this was the beginning of the end, and a mistake to undo. Enter the katechon.

I. Katechontic Drift

Paul’s Riddle

The Katechon first appears in 2 Thessalonians 2, where Paul asserts that “the mystery of lawlessness is already at work,” but it is being held back by the katechon, the restrainer: first as a what (to katechon) then as a who (ho katechōn), “until he is out of the way.” Paul never names the katechon; the point is functional, not biographical. Something / someone delays revelation of the final lawless until the appointed time; in Paul’s wider theology, that patience makes room for witness and repentance. His aim is patience for repentance, not statecraft.

Many Christian interpreters keep the katechon in a primarily spiritual register: the Holy Spirit, the Church, the preaching of the Gospel, or angelic guardians as the restrainer. But the katechon was quickly immanentized, identified as a worldly power.

Immanentizing the Katechon

Many early Church Fathers read the katechon as the Roman Empire: Tertullian1 suggests Christians pray for emperors because the Empire’s continuance delays the end; John Chrysostom explicitly identifies the Roman Empire as the katechon2. The katechon becomes provisional political order — imperfect and pagan, yet providential — so that the Church may live and speak.

Over time the katechon became a floating signifier for “legitimate order.” As Rome waned, apocalyptic writers3 tied the delay of Antichrist to Byzantium, then the Holy Roman Empire.

In Reformation polemics, the katechon became a weapon: both sides treated restraint as safeguarding their orthodoxy. For Catholics, Rome was the bulwark against heresy; for many Protestants, Rome was the Antichrist, and the magistrate was the restrainer. What’s delayed isn’t just the Antichrist but also collapse and heresy; the katechon was already sliding towards “order against chaos” language.

II. The Katechonter-Revolutionaries

De Maistre: Order Before Freedom

Joseph de Maistre never uses the Greek term katechon, but echoes the logic. Writing after the French Revolution of 1789 and the ensuing purges and guillotines of the Reign of Terror, he recasts the restrainer as sacral sovereignty.

The Revolution and Terror, he argues, were divine chastisement for a century of impiety and metaphysical hubris, and a catastrophe bearing a blunt lesson: freedom follows prior order4. Written charters and abstract rights are paper idols that succeed only when they codify an already formed moral world; when they try to fabricate one, they call up the scaffold.

In his view, the Enlightenment was metaphysical acid, leaving behind a dogmatic vacuum: skepticism, irreligion, rights-talk without foundations. Fallen, imitative humans don’t self-limit by reason; liberty is safe only after a pre-political fabric (cult, custom, clergy, magistracy, family, guilds) has formed habits of restraint. The world that can bear freedom is inherited; constitutions cannot mint the mores they presuppose5.

For that fabric to hold, sovereignty must be one and indivisible. Split sovereignty invites paralysis, faction, and blood. Hence his notorious emblem: the executioner, the solemn minister of awe before the law and the reminder that law carries weight: the law’s word matters because the sword is real6. Remove credible sanction and the edifice trembles: peace through punishment, deterrent and expiatory at once. To de Maistre, the sword is medicinal.

“All grandeur, all power, all subordination to authority rests on the executioner: he is the horror and the bond of human association. Remove this incomprehensible agent from the world and at that very moment order gives way to chaos, thrones topple and society disappears.”

— Joseph de Maistre, St Petersburg Dialogues

He yokes throne and altar, yet places Rome above thrones: the papacy serves as a supranational tribunal to discipline princes and shorten wars7. In katechontic terms, the restrainer is a sacral sovereign armed with state potestas and crowned by ecclesial auctoritas, holding back dissolution while peoples are re‑formed by inherited institutions. Sovereignty descends from God and history, not from individuals upwards. In short: order first, then liberty — a katechontic politics in all but name. Even war can be purgative under providence, another instrument of restraint; perpetual peace is a chimera.

Invert his sequence, and freedom leads to license, faction, anarchy, and eventually despotism; you get the Terror, then a Napoléon.

You will note, Slick, that the Terror’s scaffold and de Maistre’s executioner don’t look all that different. Fear and blood do the teaching. The difference is the story they serve: abstraction / refoundation, or tradition / providence. Organicism — the idea that law must codify existing mores — looks a lot like status quo bias; de Maistre’s ’tradition’ goes back to yesterday, not to the gospel. To a time that, incidentally, favoured aristocrats like him under the Ancien Régime; some would say he’s cloaking class interest in theological dress, sacralizing cruelty as ‘expiation’ and unaccountable power as ‘indivisible sovereignty’8.

De Maistre re-sacralizes permanent sovereign order. Donoso Cortés will radicalize the emergency, making the dictatorship of the moment the explicit instrument of restraint.

Donoso Cortés: Medicinal Dictatorship

In the aftershocks of the 1848 revolutions, the Spanish statesman‑theologian Juan Donoso Cortés radicalizes the katechontic instinct into decision under emergency. He argues that modern parliamentarism is a luxury of tranquil times; when nihilistic forces (for him, socialism and anarchy) breach the gates, debate must yield to dictatorship — a harsh but “medicinal” remedy that cauterizes political hemorrhage9.

Where de Maistre sacralizes indivisible sovereignty to preserve the inherited fabric, Donoso sacralizes the moment of decision itself: the ruler who suspends norms to save the body politic is not a lawbreaker but the law’s physician. Evil, he thinks, spreads by delay; celerity is charity. In this register, restraint means pre‑emption — punitive, exemplary, deterrent — so that society’s enemies fear crossing the line.

Donoso keeps the vertical metaphysics (authority descends from God, not the people) but swaps de Maistre’s organicism for catastrophism: the world is already sliding toward a terminal conflict, so temporizing is surrender. Dictatorship becomes the katechon’s scalpel, the only instrument sharp enough to hold back the Antichrist‑bearing tide.

This is the bridge to twentieth‑century decisionism: the sovereign is the one who decides on the exception, and the exception becomes the norm. Once emergency is theologized as restraint, states can punish in the name of mercy and rule indefinitely under the grammar of “saving the world.”

III. From Eschatology to State Theory: Carl Schmitt’s Secular Katechon

Donoso sacralizes dictatorship as medicine: in a fallen world, debate surrenders souls to nihilism, so a God‑authorized ruler must act swiftly to restore a pre‑given Christian order. Schmitt juridicizes and secularizes the move. No altar is needed; what holds a polity together in crisis is decision.

The Two Exceptions

Reacting to the crises of Weimar Germany, Schmitt at first argues for a crucial distinction between a commissarial emergency, delegated and time‑bound, that suspends some norms to preserve an existing constitution, and a sovereign emergency, originative and extra‑legal, that refounds the order itself. The former is required to avoid the latter10. When rules collide or fall silent, law cannot apply itself; only a locus that can decide prevents disintegration.

“Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” — Carl Schmitt, Political Theology (1922)

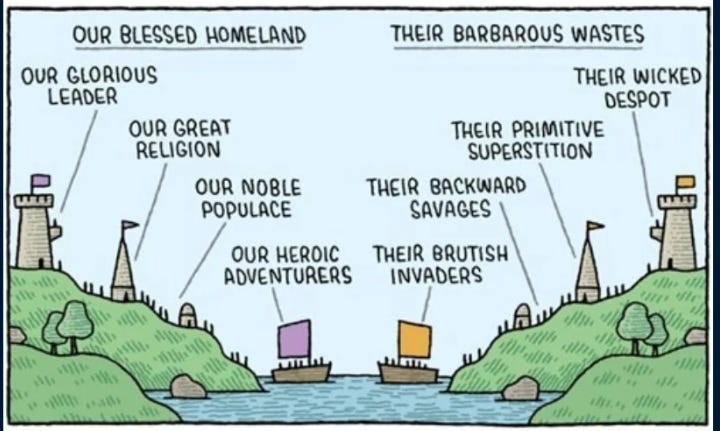

Schmitt then explains why he thinks procedure fails: the old warrant for parliament — free, public deliberation that could change minds — has hollowed out. Party discipline fixes votes; publicity becomes theater; interest‑group bargaining replaces reason‑giving; and without shared substance, procedure stalls. If deliberation cannot produce binding unity under pressure, the exception must11. He later defines politics by the friend/enemy distinction, making unity against an enemy the test of a people’s reality12.

Put together, these claims yield his verdict on liberal pluralism: procedures cannot rescue a polity once enemies press and rules collide. Unity requires a place where someone can decide.

The Jurisprudence of Dictatorship

Within Weimar, that “place” is initially legal. In Der Hüter der Verfassung (1931) Schmitt recasts the president as guardian of the constitution, constitutionalizing the restrainer through Article 48. This is the commissarial model: a defined, internal valve to keep the system from seizing up. But by Legality and Legitimacy (1932) the center of gravity shifts: legality alone cannot sustain the state; substantive unity and decision must ground it. The slope toward sovereign power is now visible.

Then comes the leap: Schmitt joins the Nazi Parti in 1933, attacks normativism, and writes in an antisemitic key13. He publicly legitimates extra‑legal violence as law‑creating; his essay “Der Führer schützt das Recht” (the Führer protects the law, 1934) retroactively clothes the Night of the Long Knives in legality. Whatever the earlier theory promised, the practice shows how a guardian slides into founder, how the exception becomes authorization for a new order.

The secular catechism of restraint becomes a jurisprudence of dictatorship: legitimacy collapses into decisional unity, authorized by emergency, so the regime that can decide and make the decision stick claims the right to rule — whatever the content.

What’s in a Katechon?

Schmitt never recanted or distanced himself from his Nazi era after 1945. Where he implicitly framed the Third Reich as a restrainer14, he later started naming the katechon outright.

In post‑war notes he writes, “the Katechon needs to be named for every epoch of the past 1948 years. The place was never unoccupied; otherwise we would no longer be present,” turning the restrainer into a historical brake: orders that “buy time” against dissolution15. In The Nomos of the Earth (1950) he elegizes the old European jus publicum for “bracketing” war; with its breakdown, “global civil war” looms. In the Cold War, he reads anti-communist order as a potential katechon: not sanctified church-and-throne, but a restraining world-nomos backed by decisive exemption.

Schmitt’s grammar is constant: pluralism is paralysis; unity requires decision; the exception founds law. That grammar proved hospitable to a racist, antisemitic dictatorship, so long as it promised unity and an enemy to restrain. That is the danger of a secularized katechon: not patience for repentance, but a standing permission for permanent emergency and an exception that can come knocking on your door to ensure “unity.”

IV. Katechonwards

Once immanentized, the restrainer slides from Spirit and witness to order-maintenance by coercion, baptizing whatever force can “buy time” in a crisis, authorizing the lesser evil to delay the worse. The logic resurfaces whenever emergency is declared: if chaos is held at bay, the means are excused as medicinal, and Christian warnings against state theology or Nazi pagan racism16 dismissed as naïve or disloyal.

This catechism is back today as the dashboard blinks red in the polycrisis: coercion as care, exception as virtue, order and unity achieved by fear. The end is nigh, Slick, and America’s new apocalyptic christians see themselves as the last rampart.

Apologeticus 32

Homilies on 2 Thessalonians

e.g., Adso of Montier-en-Der

Considerations on France, 1796

Essay on the Generative Principle of Political Constitutions, 1814

The St. Petersburg Dialogues, 1821

Du Pape, 1819

Though in all fairness, de Maistre elevates Rome above thrones and defends the teeth of law even against aristocratic ‘liberties.’ In practice, though, Rome was often a very light check on the power of kings.

Essay on Catholicism, Liberalism and Socialism, 1851

On Dictatorship, 1921

The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy, 1923

The Concept of the Political, 1932

Schmitt’s antisemitism was not incidental or merely opportunistic; it’s explicit in his 1936 lecture “The Turn to the Total State” and in writings for Nazi legal journals where he framed Jewish thinkers as corrupting German law. He curated antisemitic bibliographies for the Reichsgruppe Deutscher Juristen and defended measures to “cleanse” the legal profession. Even after being sidelined by parts of the SS, he never disavowed these positions.

According to Wolfgang Palaver, Schmitt treated the Third Reich itself as a katechontic force against a feared communist world‑state.

Glossarium, published posthumously

The Barmen Declaration, 1934; Mit brennender Sorge, 1937

Basically we're going in circles, rhyming with history.

I'm curious about whether there's any accountability for mistaken decisions in Schmitt? Beyond the imaginary, statecraft requires tracking minutae and failsafe mechanisms to reign in mistakes, which is one of those things we're lacking today. It's all good and well to highlight the descent into decadence brought about by liberalism spawning pluralism creating division, terror and eventually tyranny, yet the day after a reappointed sovereign reestablishs order, power corrupts absolutely. This has been true from Hitler to Napoleon to the original Caesar. Perhaps what set Caesar apart was that back then the Roman Empire would only get aspiring competitors a few centuries later, hence the Pax Romana eulogized an exceptional circumstance, while all aspiring sovereigns since were unable to be hegemons within their known world, so if under threat of being assailed from the outside, this thus paved the way for a perpetual emergency justifying the need of their sovereignty. The USA squandered Pax Americana the day NATO bombed FRJ in the 90s, history will write. The Church too, once divisions set in during the enlightenment, after it had switched from spiritual witness to statecraft for centuries, it's impossible not to feel future schism aspirants (like the Jesuits for instance) weren't in some way influenced by memories of its absolutist golden age, dominion, deceiving themselves to omit the way the Church had been consumed by its own power and paved the way for the emergence of its rebellious divisions.

Using postmodern imagery, either we believe Thanos had the right idea, hence we shall get holocausts until there is only one, or there'll be lurking Hydras seeking to create an Elysium just because. Perhaps we imagine a Kal-El makes an appearance to save us from ourselves, although we're kinda maybe already living downstream of the El's, so who knows what's up. It's altogether hard to reconcile how everything just seems to be coming to a decisive moment in time right now. When one statesman said to the other a few years ago, "soon we'll have conditions for changes that haven't happened in a hundred years", if anything he was understating things.

Can't wait for part 3!